| Chae Chan Ping v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 28–29, 1889 Decided May 13, 1889 | |

| Full case name | Chae Chan Ping v. United States |

| Citations | 130 U.S. 581 ( more ) 9 S. Ct. 623; 32 L. Ed. 1068; 1889 U.S. LEXIS 1778 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Appeal from the Circuit Court of the United States for the Northern District of California |

| Holding | |

| The Scott Act of 1888 is valid; immigration and nationality laws can abrogate conflicting treaties, are within federal power, and are owed judicial deference. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

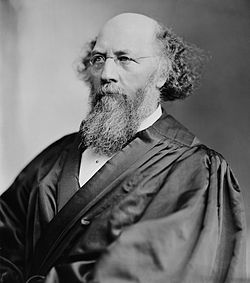

| Majority | Field, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art. III and Scott Act of 1888 | |

Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889), or The Chinese Exclusion Case, is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the constitutionality of the Scott Act of 1888, a follow-up to the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Scott Act barred Chinese laborers from reentry to the United States. [1]

Contents

- Background

- Chinese immigration and early treaties

- Chinese Exclusion Act and Scott Act

- Chae Chan Ping and lower court proceedings

- Supreme Court

- Arguments

- Decision

- Subsequent developments

- Plenary power doctrine

- 19th century developments

- 20th century developments

- 21st century developments

- See also

- References

- External links

The case arose concerning Chae Chan Ping, a Chinese man who moved to the United States in 1875, lived in San Francisco for over a decade, and whose return voyage from a trip to British Hong Kong was pending when the Scott Act became effective. [2] Ping's legal challenge to the prohibition on reentry was aided by Chinese immigrant groups and advocated on his behalf by an elite "dream team" of lawyers. [3]

The case is viewed as "the grandfather of immigration law cases" and is significant in the broad judicial deference given to the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, as well as precedent for the plenary power and consular nonreviewability doctrines in immigration and nationality law. [4] [5]