Naturalization is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the United Nations excludes citizenship that is automatically acquired or is acquired by declaration. Naturalization usually involves an application or a motion and approval by legal authorities. The rules of naturalization vary from country to country but typically include a promise to obey and uphold that country's laws and taking and subscribing to an oath of allegiance, and may specify other requirements such as a minimum legal residency and adequate knowledge of the national dominant language or culture. To counter multiple citizenship, some countries require that applicants for naturalization renounce any other citizenship that they currently hold, but whether this renunciation actually causes loss of original citizenship, as seen by the host country and by the original country, will depend on the laws of the countries involved. Arguments for increasing naturalization include reducing backlogs in naturalization applications and reshaping the electorate of the country.

A visa is a conditional authorization granted by a polity to a foreigner that allows them to enter, remain within, or leave its territory. Visas typically include limits on the duration of the foreigner's stay, areas within the country they may enter, the dates they may enter, the number of permitted visits, or if the individual can work in the country in question. Visas are associated with the request for permission to enter a territory and thus are, in most countries, distinct from actual formal permission for an alien to enter and remain in the country. In each instance, a visa is subject to entry permission by an immigration official at the time of actual entry and can be revoked at any time. Visa evidence most commonly takes the form of a sticker endorsed in the applicant's passport or other travel document but may also exist electronically. Some countries no longer issue physical visa evidence, instead recording details only in immigration databases.

Jason Thomas Kenney is a former Canadian politician who served as the 18th premier of Alberta from 2019 until 2022, and the leader of the United Conservative Party (UCP) from 2017 until 2022. He also served as the member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Calgary-Lougheed from 2017 until 2022. Kenney was the last leader of the Alberta Progressive Conservative Party before the party merged with the Wildrose Party to form the UCP. Prior to entering Alberta provincial politics, he served in various cabinet posts under Prime Minister Stephen Harper from 2006 to 2015.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada is the department of the Government of Canada with responsibility for matters dealing with immigration to Canada, refugees, and Canadian citizenship. The department was established in 1994 following a reorganization.

Canadian nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Canada. The primary law governing these regulations is the Citizenship Act, which came into force on February 15, 1977 and is applicable to all provinces and territories of Canada.

Permanent residency is a person's legal resident status in a country or territory of which such person is not a citizen but where they have the right to reside on a permanent basis. This is usually for a permanent period; a person with such legal status is known as a permanent resident.

The right of abode is an individual's freedom from immigration control in a particular country. A person who has the right of abode in a country does not need permission from the government to enter the country and can live and work there without restriction, and is immune from removal and deportation.

This article concerns the history of British nationality law.

The permanent resident card also known colloquially as the PR card or the Maple Leaf card, is an identification document and a travel document that shows that a person has permanent residency in Canada. It is one of the methods by which Canadian permanent residents can prove their permanent residency status in Canada, and is one of the only documents that allow permanent residents to return to Canada by a commercial carrier.

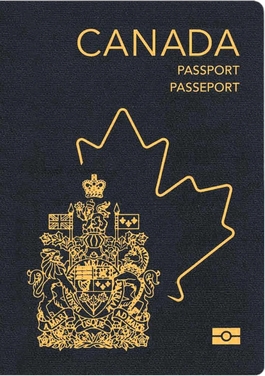

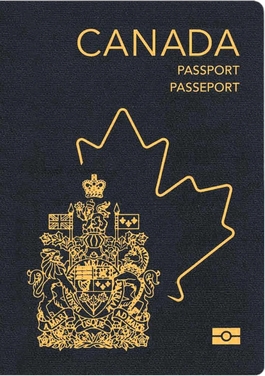

A Canadian passport is the passport issued to citizens of Canada. It enables the bearer to enter or re-enter Canada freely; travel to and from other countries in accordance with visa requirements; facilitates the process of securing assistance from Canadian consular officials abroad, if necessary; and requests protection for the bearer while abroad.

The right of abode (ROA) is an immigration status in the United Kingdom that gives a person the unrestricted right to enter and live in the UK. It was introduced by the Immigration Act 1971 which went into effect on 1 January 1973. This status is held by British citizens, certain British subjects, as well as certain Commonwealth citizens with specific connections to the UK before 1983. Since 1983, it is not possible for a person to acquire this status without being a British citizen.

A travel document is an identity document issued by a government or international entity pursuant to international agreements to enable individuals to clear border control measures. Travel documents usually assure other governments that the bearer may return to the issuing country, and are often issued in booklet form to allow other governments to place visas as well as entry and exit stamps into them.

Israeli citizenship law details the conditions by which a person holds citizenship of Israel. The two primary pieces of legislation governing these requirements are the 1950 Law of Return and 1952 Citizenship Law.

The history of immigration to Canada details the movement of people to modern-day Canada. The modern Canadian legal regime was founded in 1867, but Canada also has legal and cultural continuity with French and British colonies in North America that go back to the 17th century, and during the colonial era, immigration was a major political and economic issue with Britain and France competing to fill their colonies with loyal settlers. Until then, the land that now makes up Canada was inhabited by many distinct Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples contributed significantly to the culture and economy of the early European colonies to which was added several waves of European immigration. More recently, the source of migrants to Canada has shifted away from Europe and towards Asia and Africa. Canada's cultural identity has evolved constantly in tandem with changes in immigration patterns.

Palestinian people have a history that is often linked to the history of the Arab Nation. Upon the advent of Islam, Christianity was the major religion of Byzantine Palestine. Soon after the rise of Islam, Palestine was conquered and brought into the rapidly expanding Islamic empire. The Umayyad empire was the first of three successive dynasties to dominate the Arab-Islamic world and rule Palestine, followed by the Abbasids and the Fatimids. Muslim rule was briefly challenged and interrupted in parts of Palestine during the Crusades, but was restored under the Mamluks.

The primary law governing nationality in the United Kingdom is the British Nationality Act 1981, which came into force on 1 January 1983. Regulations apply to the British Islands, which include the UK itself and the Crown dependencies ; and the 14 British Overseas Territories.

The visa policy of Canada requires that any foreign citizen wishing to enter Canada must obtain a temporary resident visa from one of the Canadian diplomatic missions unless they hold a passport issued by one of the 53 eligible visa-exempt countries and territories or proof of permanent residence in Canada or the United States.

The Palestinian Authority Passport is a passport/travel document issued since April 1995 by the Palestinian Authority to Palestinian residents of the Palestinian territories for the purpose of international travel.

Multiple citizenship is a person's legal status in which a person is at the same time recognized by more than one country under its nationality and citizenship law as a national or citizen of that country. There is no international convention that determines the nationality or citizenship status of a person, which is consequently determined exclusively under national laws, which often conflict with each other, thus allowing for multiple citizenship situations to arise.

The Kuwaiti nationality law is the legal pathway for non-nationals to become citizens of the State of Kuwait. The Kuwaiti nationality law is based on a wide range of decrees; first passed in 1920 and then in 1959 and 1960. A number of amendments have been made over the years. Since the 1960s, the implementation of the nationality law has been very arbitrary and lacks transparency. The lack of transparency prevents non-nationals from receiving a fair opportunity to obtain citizenship.