A proverb is a simple, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and use formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbial expression is a type of a conventional saying similar to proverbs and transmitted by oral tradition. The difference is that a proverb is a fixed expression, while a proverbial phrase permits alterations to fit the grammar of the context. Collectively, they form a genre of folklore.

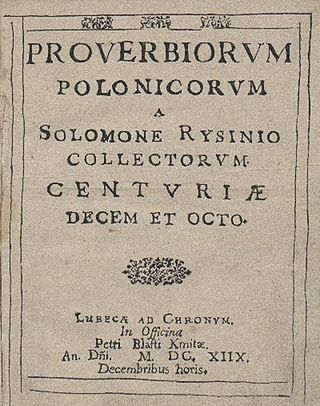

Tens of thousands of Polish proverbs exist; many have origins in the Middle Ages. The oldest known Polish proverb dates to 1407. A number of scholarly studies of Polish proverbs (paremiology) exist; and Polish proverbs have been collected in numerous dictionaries and similar works from the 17th century onward. Studies in Polish paremiology have begun in the 19th century. The largest and most reputable collection of Polish proverbs to date, edited by Julian Krzyżanowski, was published in 1970s.

A Japanese proverb may take the form of:

Chengyu are a type of traditional Chinese idiomatic expressions, most of which consist of four characters. Chengyu were widely used in Classical Chinese and are still common in vernacular Chinese writing and in the spoken language today. According to the most stringent definition, there are about 5,000 chéngyǔ in the Chinese language, though some dictionaries list over 20,000. Chéngyǔ are considered the collected wisdom of the Chinese culture, and contain the experiences, moral concepts, and admonishments from previous generations of Chinese speakers. Nowadays, chéngyǔ still play an important role in Chinese conversations and education. Chinese idioms are one of four types of formulaic expressions, which also include collocations, two-part allegorical sayings, and proverbs.

In language, an archaism is a word, a sense of a word, or a style of speech or writing that belongs to a historical epoch beyond living memory, but that has survived in a few practical settings or affairs. Lexical archaisms are single archaic words or expressions used regularly in an affair or freely; literary archaism is the survival of archaic language in a traditional literary text such as a nursery rhyme or the deliberate use of a style characteristic of an earlier age—for example, in his 1960 novel The Sot-Weed Factor, John Barth writes in an 18th-century style. Archaic words or expressions may have distinctive emotional connotations—some can be humorous (forsooth), some highly formal, and some solemn. The word archaism is from the Ancient Greek: ἀρχαϊκός, archaïkós, 'old-fashioned, antiquated', ultimately ἀρχαῖος, archaîos, 'from the beginning, ancient'.

An aphorism is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tradition from generation to generation.

"May you live in interesting times" is an English expression that is claimed to be a translation of a traditional Chinese curse. The expression is ironic: "interesting" times are usually times of trouble.

"Mind over matter" is a phrase that has been used in several contexts, such as mind-centric spiritual doctrines, parapsychology, and philosophy.

"A picture is worth a thousand words" is an adage in multiple languages meaning that complex and sometimes multiple ideas can be conveyed by a single still image, which conveys its meaning or essence more effectively than a mere verbal description.

The word junzi is a Chinese philosophical term often translated as "gentleman," "superior person", or "noble man." The term is frequently translated as "gentleman", since the characters are overtly gendered. However, in recent years, scholars have been using the term without the gender component, and translate the term as "distinguished person", "moral person", and so on. The characters 君子 were employed both the Duke Wen of Zhou in the "Classic of Changes" 易經 (I-ching) and Confucius in his works to describe the ideal man.

Paremiology is the collection and study of paroemias (proverbs). It is a subfield of both philology and linguistics.

Blood is thicker than water is a proverb in English meaning that familial bonds will always be stronger than other relationships. The oldest record of this saying can be traced back to the 12th century in German.

The camel's nose is a metaphor for a situation where the permitting of a small, seemingly innocuous act will open the door for larger, clearly undesirable actions.

Xiehouyu is a kind of Chinese proverb consisting of two elements: the former segment presents a novel scenario while the latter provides the rationale thereof. One would often only state the first part, expecting the listener to know the second. Compare English "an apple a day " or "speak of the devil ".

"The devil is in the details" is an idiom alluding to a catch or mysterious element hidden in the details; it indicates that "something may seem simple, but in fact the details are complicated and likely to cause problems". It comes from the earlier phrase "God is in the details", expressing the idea that whatever one does should be done thoroughly; that is, details are important.

When in Rome, do as the Romans do, or a later version when in Rome, do as the Pope does, is a proverb attributed to Saint Ambrose. The proverb means that it is best to follow the traditions or customs of a place being visited.

"When two tigers fight" is a Chinese proverb or chengyu. It refers to the inevitability that when rivals clash, even though they are great figures, one of them must fall.

"Paradisus Judaeorum" is a Latin phrase which became one of four members of a 19th-century Polish-language proverb that described the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) as "heaven for the nobility, purgatory for townspeople, hell for peasants, paradise for Jews." The proverb's earliest attestation is an anonymous 1606 Latin pasquinade that begins, "Regnum Polonorum est". Stanisław Kot surmised that its author may have been a Catholic townsman, perhaps a cleric, who criticized what he regarded as defects of the realm; the pasquinade excoriates virtually every group and class of society.

Birds of a feather flock together is an English proverb. The meaning is that beings of similar type, interest, personality, character, or other distinctive attribute tend to mutually associate.

Complete Treatise on Agriculture, or Complete Book of Agricultural Management, or Encyclopaedia of Agriculture, is a compilation of the scientific studies of agriculture written by Xu Guangqi. The book was composed from 1625 to 1628 and published in 1639, totalling 700,000 words.