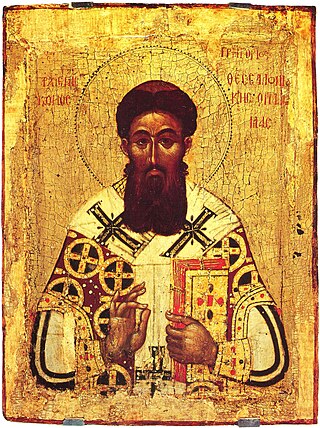

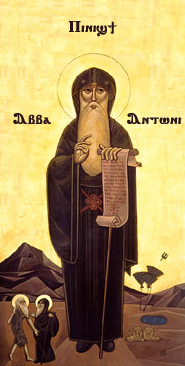

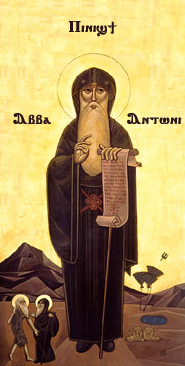

Anthony the Great was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony, such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets: Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar.

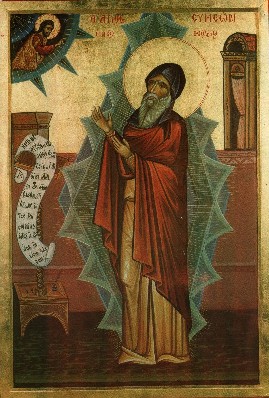

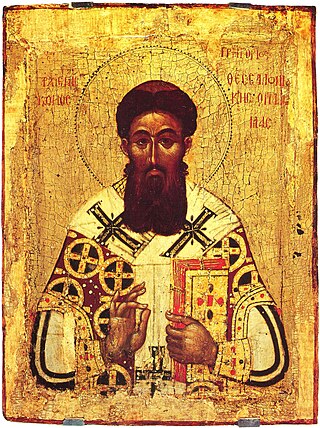

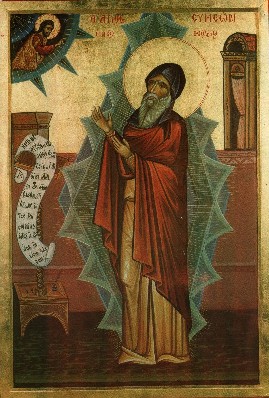

Hesychasm is a contemplative monastic tradition in the Eastern Christian traditions of the Eastern Catholic Churches and Eastern Orthodox Church in which stillness (hēsychia) is sought through uninterrupted Jesus prayer. While rooted in early Christian monasticism, it took its definitive form in the 14th century at Mount Athos.

Monasticism, lso called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially in the Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican traditions as well as in other faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. In other religions, monasticism is generally criticized and not practiced, as in Islam and Zoroastrianism, or plays a marginal role, as in modern Judaism.

Pachomius, also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, and Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches mark his feast on 15 May or 28 May. In Lutheranism, he is remembered as a renewer of the church, along with his contemporary, Anthony of Egypt on 17 January.

Montanism, known by its adherents as the New Revelation, was an early Christian movement of the late 2nd century, later referred to by the name of its founder, Montanus. Montanism held views about the basic tenets of Christian theology similar to those of the wider Christian Church, but it was labelled a heresy for its belief in new prophetic figures. The prophetic movement called for a reliance on the spontaneity of the Holy Spirit and a more conservative personal ethic.

Christian mysticism is the tradition of mystical practices and mystical theology within Christianity which "concerns the preparation [of the person] for, the consciousness of, and the effect of [...] a direct and transformative presence of God" or divine love. Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria, from contemplatio, "looking at", "gazing at", "being aware of" God or the divine. Christianity took up the use of both the Greek (theoria) and Latin terminology to describe various forms of prayer and the process of coming to know God.

Christian monasticism is a religious way of life of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament. It has come to be regulated by religious rules and, in modern times, the Canon law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). The word monk originated from the Greek μοναχός, itself from μόνος meaning 'alone'.

Cenobiticmonasticism is a monastic tradition that stresses community life. Often in the West the community belongs to a religious order, and the life of the cenobitic monk is regulated by a religious rule, a collection of precepts. The older style of monasticism, to live as a hermit, is called eremitic. A third form of monasticism, found primarily in Eastern Christianity, is the skete.

Mar Awgin or Awgen, also known as Awgin of Clysma or Saint Eugenios, was an Egyptian monk who, according to traditional accounts, introduced Christian monasticism to Syriac Christianity. These accounts, however, are all of late origin and often contain anachronisms. The historicity of Awgin is not certain.

John Cassian, also known as John the Ascetic and John Cassian the Roman, was a Christian monk and theologian celebrated in both the Western and Eastern churches for his mystical writings. Cassian is noted for his role in bringing the ideas and practices of early Christian monasticism to the medieval West.

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt, beginning around the third century AD. The Apophthegmata Patrum is a collection of the wisdom of some of the early desert monks and nuns, in print as Sayings of the Desert Fathers. The first Desert Father was Paul of Thebes, and the most well known was Anthony the Great, who moved to the desert in AD 270–271 and became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony had died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example, leading his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, to write that "the desert had become a city." The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

Shenoute of Atripe, also known as Shenoute the Great or Saint Shenoute the Archimandrite was the abbot of the White Monastery in Egypt. He is considered a saint by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and is one of the most renowned saints of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Nilus of Sora was a Russian Orthodox monk, spiritual writer, theologian, and the founder of the Sora Hermitage. He is best known as the founder of a tendency in the Russian Orthodox Church known as the non-possessors (nestyazhateli) which opposed ecclesiastic landownership. The Russian Orthodox Church venerates Nilus as a saint, marking his feast day on the anniversary of his repose on 7 May.

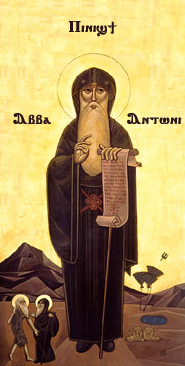

Saint Symeon the New Theologian was an Eastern Orthodox monk and poet who was one of the four saints canonized by the Eastern Orthodox Church and given the title of "Theologian". "Theologian" was not applied to Symeon in the modern academic sense of theological study; the title was intended only to recognize someone who spoke from personal experience of the vision of God. One of his principal teachings was that humans could and should experience theoria.

Monastic settlements are areas built up in and around the development of monasteries with the spread of Christianity. To understand Christian monastic settlements, we must understand a brief history of Christian monasticism. Monasticism was a movement especially associated with Early Christianity that began in the late 3rd century to the 4th century in Egypt when early Christians realizing that martyrdom wasn’t much of an option when the Roman empire relaxed Christian persecutions. It was begun by key monks who were known then as “The Desert Fathers” and later, there were female monasteries run by women who later came to be known as “The Desert Mothers”. The most famous Desert Father was Abba Anthony and the most famous Desert Mother was Amma Syncletica.ost of the Christians took to the deserts and arid areas to deny themselves of the social environments and people in order to focus on God and prayer. They denied themselves of a comfortable life often resorting to eating what grew in the deserts as well as living frugally and in poverty. With time, monasticism came to impact the church and even the papacy and there came about two variants of monasticism: The Eastern Monastic movement and the Western Monastic movement. Inspired by the Eastern monastic movements, new monastic movements sprung up in western Europe after the Roman empire fell apart and newer kingdoms like the Franks, Britannia and Germanic tribes sprung up. The papacy was at its infancy and places like the Isles of Britannia had monks that established monasteries along its coastlines. One of the forerunners was St. Augustine whose Rule became encoded in the future doctrine of the Roman clergy of the church.

Eastern Christian monasticism is the life followed by monks and nuns of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East and some Eastern Catholic Churches.

Coptic monasticism was a movement in the Coptic Orthodox Church to create a holy, separate class of person from layman Christians.

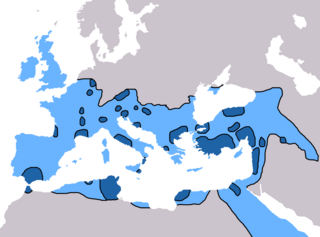

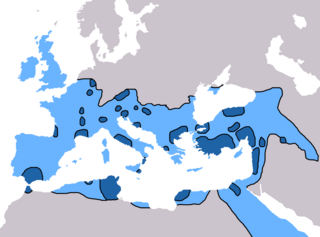

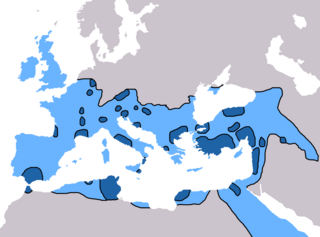

Christianity in the 4th century was dominated in its early stage by Constantine the Great and the First Council of Nicaea of 325, which was the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787), and in its late stage by the Edict of Thessalonica of 380, which made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.

In the 5th century in Christianity, there were many developments which led to further fracturing of the State church of the Roman Empire. Emperor Theodosius II called two synods in Ephesus, one in 431 and one in 449, that addressed the teachings of Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius and similar teachings. Nestorius had taught that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons, and hence Mary was the mother of Christ but not the mother of God. The Council rejected Nestorius' view causing many churches, centered on the School of Edessa, to a Nestorian break with the imperial church. Persecuted within the Roman Empire, many Nestorians fled to Persia and joined the Sassanid Church thereby making it a center of Nestorianism. By the end of the 5th century, the global Christian population was estimated at 10-11 million. In 451 the Council of Chalcedon was held to clarify the issue further. The council ultimately stated that Christ's divine and human nature were separate but both part of a single entity, a viewpoint rejected by many churches who called themselves miaphysites. The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches, that is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy. In spite of these schisms, however, the imperial church still came to represent the majority of Christians within the Roman Empire.

Prayer has been an essential part of Christianity since its earliest days. As the Middle Ages began, the monastic traditions of both Western and Eastern Christianity moved beyond vocal prayer to Christian meditation. These progressions resulted in two distinct and different meditative practices: Lectio Divina in the West and hesychasm in the East. Hesychasm involves the repetition of the Jesus Prayer, but Lectio Divina uses different Scripture passages at different times and although a passage may be repeated a few times, Lectio Divina is not repetitive in nature.