The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended between 4000 BC and 2000 BC, with the advent of metalworking. It therefore represents nearly 99.3% of human history. Though some simple metalworking of malleable metals, particularly the use of gold and copper for purposes of ornamentation, was known in the Stone Age, it is the melting and smelting of copper that marks the end of the Stone Age. In Western Asia, this occurred by about 3000 BC, when bronze became widespread. The term Bronze Age is used to describe the period that followed the Stone Age, as well as to describe cultures that had developed techniques and technologies for working copper alloys into tools, supplanting stone in many uses.

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or knapped stone, the latter fashioned by a craftsman called a flintknapper. Stone has been used to make a wide variety of tools throughout history, including arrowheads, spearheads, hand axes, and querns. Knapped stone tools are nearly ubiquitous in pre-metal-using societies because they are easily manufactured, the tool stone raw material is usually plentiful, and they are easy to transport and sharpen.

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-sided ravine in the Great Rift Valley that stretches across East Africa, it is about 48 km long, and is located in the eastern Serengeti Plains within the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in the Olbalbal ward located in Ngorongoro District of Arusha Region, about 45 kilometres from Laetoli, another important archaeological locality of early human occupation. The British/Kenyan paleoanthropologist-archeologist team of Mary and Louis Leakey established excavation and research programs at Olduvai Gorge that achieved great advances in human knowledge. The site is registered as one of the National Historic Sites of Tanzania.

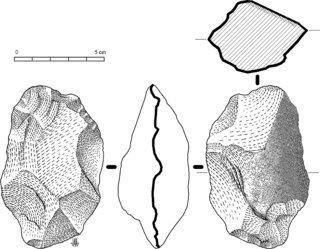

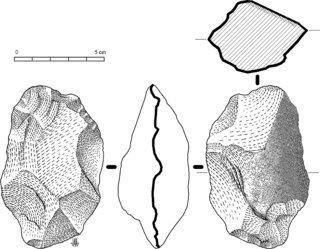

A hand axe is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by knapping, or hitting against another stone. They are characteristic of the lower Acheulean and middle Palaeolithic (Mousterian) periods, roughly 1.6 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago, and used by Homo erectus and other early humans, but rarely by Homo sapiens.

Acheulean, from the French acheuléen after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with Homo erectus and derived species such as Homo heidelbergensis.

The Oldowan was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made by chipping one, or a few, flakes off a stone using another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower Paleolithic period, 2.9 million years ago up until at least 1.7 million years ago (Ma), by ancient Hominins across much of Africa. This technological industry was followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry.

Abbevillian is a term for the oldest lithic industry found in Europe, dated to between roughly 600,000 and 400,000 years ago.

Swanscombe /ˈswɒnzkəm/ is a village in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England, and the civil parish of Swanscombe and Greenhithe. It is 4.4 miles west of Gravesend and 4.8 miles east of Dartford.

The Lower Paleolithic is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears in the current archaeological record, until around 300,000 years ago, spanning the Oldowan and Acheulean lithics industries.

Hoxne is a village in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England, about five miles (8 km) east-southeast of Diss, Norfolk and 1⁄2 mile (800 m) south of the River Waveney. The parish is irregularly shaped, covering the villages of Hoxne, Cross Street and Heckfield Green, with a 'tongue' extending southwards to take in part of the former RAF Horham airfield.

Archaeologists define a chopper as a pebble tool with an irregular cutting edge formed through the removal of flakes from one side of a stone.

A ficron handaxe is the name given to a type of prehistoric stone tool biface with long, curved sides and a pointed, well-made tip. They are found in Lower Palaeolithic, Middle Palaeolithic and Acheulean contexts, and are some of the oldest tools ever created by humans. The tool was named by the French archaeologist François Bordes.

In archaeology, a cleaver is a type of biface stone tool of the Lower Palaeolithic.

The Boxgrove Palaeolithic site is an internationally important archaeological site north-east of Boxgrove in West Sussex with findings that date to the Lower Palaeolithic. The oldest human remains in Britain have been discovered on the site, fossils of Homo heidelbergensis dating to 500,000 years ago. Boxgrove is also one of the oldest sites in Europe with direct evidence of hunting and butchering by early humans. Only part of the site is protected through designation, one area being a 9.8-hectare (24-acre) geological Site of Special Scientific Interest, as well as a Geological Conservation Review site.

Swanscombe Skull Site or Swanscombe Heritage Park is a 3.9-hectare (9.6-acre) geological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Swanscombe, north-west Kent, England. It contains two Geological Conservation Review sites and a National Nature Reserve. The park lies in a former gravel quarry, Barnfield Pit, which is the most important site in the Swanscombe complex, alongside several other nearby pits.

Clacton Cliffs and Foreshore is a 26.1-hectare (64-acre) geological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Clacton-on-Sea in Essex. It is a Geological Conservation Review site.

The Clacton Spear, or Clacton Spear Point, is the tip of a wooden spear discovered in Clacton-on-Sea in 1911. At approximately 400,000 years old, it is the oldest known worked wooden implement.

Chequer's Wood and Old Park is a 106.9-hectare (264-acre) biological and geological Site of Special Scientific Interest on the eastern outskirts of Canterbury in Kent. It is a Geological Conservation Review site.

Beeches Pit is an archaeological site in Suffolk, England, dated to around 0.4 million years ago. It contains palaeoenvironmental remains, and is particularly notable because it provides evidence of the human use of fire, the earliest in Britain. In addition, knapping debris and Acheulean hand axes have been found. It is one of the richest sites in England for evidence of human activity during that period, and the hand axes are the "earliest post-Anglian handaxe-making horizon in Britain".

Dama clactoniana is an extinct species of fallow deer. It lived during the Middle Pleistocene. It is widely agreed to be the Dama species most closely related and likely ancestral to the two living species of fallow deer and like them has palmate antlers.