Archaeology

The name of the archaeological culture derives from sites in the district of Trialeti in south Georgian Khrami river basin. These sites include Barmaksyzkaya and Edzani-Zurtaketi. [3] In Edzani, an Upper Paleolithic site, a significant percentage of the artifacts are made of obsidian. [4]

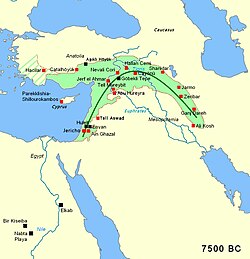

The Caucasian-Anatolian area of Trialetian culture was adjacent to the Iraqi-Iranian Zarzian culture to the east and south as well as the Levantine Natufian to the southwest. [5] Alan H. Simmons describes the culture as "very poorly documented". [6] In contrast, recent excavations in the Valley of Qvirila river, to the north of the Trialetian region, display a Mesolithic culture.[ citation needed ] The subsistence of these groups were based on hunting Capra caucasica , wild boar and brown bear. [7]

Trialetian sites

Caucasus and Transcaucasia:

- Edzani (Georgia) [9]

- Chokh (Azerbaijan), layers E-C200 [9]

- Kotias Klde, layer B [10]

Eastern Anatolia:

- Hallan Çemi [9] (from ca. 8.6-8.5k BC to 7.6-7.5k BC [10] )

- Nevali Çori shows some Trialetian admixture in a PPNB context [9]

Trialetian influences can also be found in:

- Cafer Höyük [9]

- Boy Tepe [9]

Southeast of the Caspian Sea:

- Hotu (Iran) [9]

- Ali Tepe (Iran) [9] (from cal. 10.5k BC to 8.87 BC [10] )

- Belt Cave (Iran), layers 28-11 [9] (the last remains date from ca. 6k BC [10] )

- Dam-Dam-Cheshme II (Turkmenistan), layers7-3 [9]

The belonging of these Caspian Mesolithic sites to the Trialetian has been questioned. [11]

Relation with the Caspian Mesolithic

Differences have been found [11] between the Trialetian and the Caspian Mesolithic of the southeastern part of the Caspian Sea (represented by sites like Komishan, Hotu, Kamarband and Ali Tepe), even though the Caspian Mesolithic had previously been attributed to Trialetian by Kozłowski (1994, 1996 and 1999), Kozłowski and Aurenche 2005 and Peregrine and Ember 2002. These differences have been established through a detailed study of the site of Komishan and are driven by the underlying differences at the level of cultural ecology.

While Trialetian industry developed in steppe riparian and mountain ecozones, as for example in the Khrami river and the mountainous site of Chokh respectively, the Caspian Mesolithic took place in a transitional ecotone between the sea (Caspian Sea), plain and mountains (Alborz mountain range). The Caspian Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were adapted to the exploitation of marine resources and had access to high quality raw material, whereas in the Trialetian sites as Chokh and Trialeti there is imported raw material from distances of 100 km.

Relation with Kmlo-2

Kmlo-2 is a rock shelter situated on the west slope of the Kasakh River valley, [12] on the Aragats massif, in Armenia. This site seems to present three different phases of occupation (11-10k cal BC, 9-8k cal BC and 6-5k cal BC). [12] [13] [14] The lithic industry of the three phases show similarities such as the predominance of microliths, small cores and obsidian as raw material. [12] [14] The backed an scalene bladelets are the dominant type of microlith; these tools show similarities with those of the Late Upper Paleolithic of Kalavan-1 and the Mesolithic layer B of the Kotias Klde. [14] Cultural affinities of the Kmlo-2 lithic industry with the Epipaleolithic and Aceramic Neolithic sites in Taurus-Zagros mountains have also been noted. [15]

Let us quote a few words from Gasparyan [14] about the industry found in Apnagyugh-8 (Kmlo-2) cave that express these similarities:

Let us conclude that Apnagyugh-8 industry is closer to the production complexes with traditions of Mesolithic and/or Upper Paleolithic periods. But it’s difficult to show any culture or archaeological source in Armenia today, which belongs to these periods, preceding Apnagyugh-8 and could have been its origin or prototype. The only site that emerged before Apnagyugh-8 is Kalavan-1, an Upper Paleolithic site dating to 16th–14th millennia B.C., where microliths of geometrical forms are fully absent. Though Apnagyugh-8 industry shows some similarities with Zarzian and Trialeti cultures, analytic studies for proving this comparison are still in the process.

Layer III of Kmlo-2 contained the so-called “Kmlo tools”. [16] Kmlo tools are characterized by "continuous and parallel retouch by pressure flaking of one or both lateral edges". [12] Similar tools have been found, as the associated to the Paluri-Nagutny culture in Georgia), [12] the so-called "Çayönü tools” (Çayönü, Cafer Höyük, Shimshara), [12] [13] found in Neolithic sites from the 8th to 7th millennia BC in eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia, and some found in the layer A2 of the Kotias Klde cave. [16] It has been suggested that the Kmlo tools are distinctive features of a culture established circa 9-8k cal BC on the highlands of western Armenia and continued at least until the 6th-5th millennia calBC. [13] A local development of the Kmlo tools has also been hypothesized. [13]

Final phase

Little is known about the end of the Trialetian. 6k BC has been proposed as the time on which the decline phase took place. [9] From this date are the first evidence of the Jeitunian, an industry that has probably evolved from the Trialetian. Also from this date are the first pieces of evidence of Neolithic materials in the Belt cave.

In the southwest corner of the Trialetian region it has been proposed [9] that this culture evolved towards a local version of the PPNB around 7k BC, in sites as Cafer Höyük.

Kozłowski suggests that the Trialetian does not seem to have continuation in the Neolithic of Georgia (as for example in Paluri and Kobuleti). Although in the 5k BC certain microliths similar to those of the Trialetian reappear in Shulaveris Gora (see Shulaveri-Shomu) and Irmis Gora.