The Balts or Baltic peoples are a group of peoples inhabiting the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea who speak Baltic languages. Among the Baltic peoples are modern-day Lithuanians and Latvians — all East Balts — as well as the Old Prussians, Curonians, Sudovians, Skalvians, Yotvingians and Galindians — the West Balts — whose languages and cultures are now extinct.

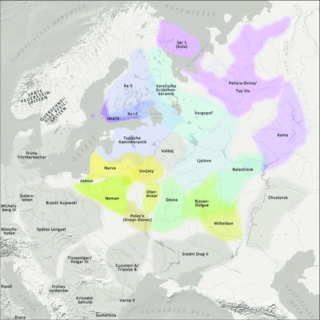

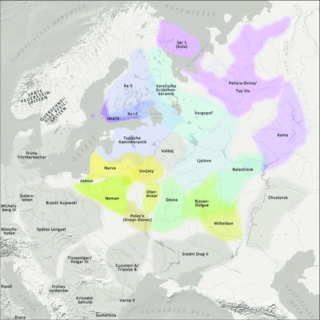

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK, was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe. It developed as a technological merger of local neolithic and mesolithic techno-complexes between the lower Elbe and middle Vistula rivers. These predecessors were the (Danubian) Lengyel-influenced Stroke-ornamented ware culture (STK) groups/Late Lengyel and Baden-Boleráz in the southeast, Rössen groups in the southwest and the Ertebølle-Ellerbek groups in the north. The TRB introduced farming and husbandry as major food sources to the pottery-using hunter-gatherers north of this line.

The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture, also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers, dating to 3300–2600 BC. It was discovered by Vasily Gorodtsov following his archaeological excavations near the Donets River in 1901–1903. Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: Я́мная is a Russian adjective that means 'related to pits ', as these people used to bury their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers. Research in recent years has found that Mikhaylovka, in lower Dnieper river, Ukraine, formed the Core Yamnaya culture.

The Comb Ceramic culture or Pit-Comb Ware culture, often abbreviated as CCC or PCW, was a northeast European culture characterised by its Pit–Comb Ware. It existed from around 4200 BCE to around 2000 BCE. The bearers of the Comb Ceramic culture are thought to have still mostly followed the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, with traces of early agriculture.

Cardium pottery or Cardial ware is a Neolithic decorative style that gets its name from the imprinting of the clay with the heart-shaped shell of the Corculum cardissa, a member of the cockle family Cardiidae. These forms of pottery are in turn used to define the Neolithic culture which produced and spread them, commonly called the "Cardial culture".

The Globular Amphora culture (GAC, German: Kugelamphoren-Kultur ; c. 3400–2800 BC, is an archaeological culture in Central Europe. Marija Gimbutas assumed an Indo-European origin, though this is contradicted by newer genetic studies that show a connection to the earlier wave of Early European Farmers rather than to Western Steppe Herders from the Ukrainian and south-western Russian steppes.

The Sredny Stog culture or Serednii Stih culture is a pre-Kurgan archaeological culture from the mid. 5th – mid. 4th millennia BC. It is named after the Dnieper river islet of today's Serednii Stih, Ukraine, where it was first located.

The Khvalynsk culture is a Middle Copper Age Eneolithic culture of the middle Volga region. It takes its name from Khvalynsk in Saratov Oblast. It was preceded by the Early Eneolithic Samara culture.

The Dnieper–Donets culture complex (DDCC) is a Mesolithic and later Neolithic archaeological culture found north of the Black Sea and dating to ca. 5000-4200 BC. It has many parallels with the Samara culture, and was succeeded by the Sredny Stog culture.

The Pitted Ware culture was a hunter-gatherer culture in southern Scandinavia, mainly along the coasts of Svealand, Götaland, Åland, north-eastern Denmark and southern Norway. Despite its Mesolithic economy, it is by convention classed as Neolithic, since it falls within the period in which farming reached Scandinavia. The Pitted Ware people were largely maritime hunters, and were engaged in lively trade with both the agricultural communities of the Scandinavian interior and other hunter-gatherers of the Baltic Sea.

The Battle Axe culture, also called Boat Axe culture, is a Chalcolithic culture that flourished in the coastal areas of the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula and southwest Finland, from c. 2800 BC – c. 2300 BC. It was an offshoot of the Corded Ware culture, and replaced the Funnelbeaker culture in southern Scandinavia, probably through a process of mass migration and population replacement. It is thought to have been responsible for spreading Indo-European languages and other elements of Indo-European culture to the region. It co-existed for a time with the hunter-gatherer Pitted Ware culture, which it eventually absorbed, developing into the Nordic Bronze Age. The Nordic Bronze Age has, in turn, been considered ancestral to the Germanic peoples.

The Kunda culture, which originated from the Swiderian culture, comprised Mesolithic hunter-gatherer communities of the Baltic forest zone extending eastwards through Latvia into northern Russia, dating to the period 8500–5000 BC according to calibrated radiocarbon dating. It is named after the Estonian town of Kunda, about 110 kilometres (70 mi) east of Tallinn along the Gulf of Finland, near where the first extensively studied settlement was discovered on Lammasmäe Hill and in the surrounding peat bog. The oldest known settlement of the Kunda culture in Estonia is Pulli. The Kunda culture was succeeded by the Narva culture, who used pottery and showed some traces of food production.

The archaeological Neman culture existed from about 5100 to the 3rd millennium BC, starting in the Mesolithic and continued into the middle Neolithic. It was located in the upper basin of the Neman River. In the north, the Neman culture bordered the Kunda culture during the Mesolithic and the Narva culture during the Neolithic.

Early European Farmers (EEF) were a group of the Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) who brought agriculture to Europe and Northwest Africa. The Anatolian Neolithic Farmers were an ancestral component, first identified in farmers from Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor) in the Neolithic, and outside in Europe and Northwest Africa, they also existed in Iranian Plateau, South Caucasus, Mesopotamia and Levant. Although the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe has long been recognised through archaeology, it is only recent advances in archaeogenetics that have confirmed that this spread was strongly correlated with a migration of these farmers, and was not just a cultural exchange.

In archaeogenetics, western hunter-gatherer is a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who scattered over western, southern and central Europe, from the British Isles in the west to the Carpathians in the east, following the retreat of the ice sheet of the Last Glacial Maximum. It is closely associated and sometimes considered synonymous with the concept of the Villabruna cluster, named after Ripari Villabruna cave in Italy, known from the terminal Pleistocene of Europe, which is largely ancestral to later WHG populations.

In archaeogenetics, eastern hunter-gatherer (EHG), sometimes east European hunter-gatherer or eastern European hunter-gatherer, is a distinct ancestral component that represents Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Eastern Europe.

In archaeogenetics, the term Scandinavian hunter-gatherer (SHG) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Scandinavia. Genetic studies suggest that the SHGs were a mix of western hunter-gatherers (WHGs) initially populating Scandinavia from the south during the Holocene, and eastern hunter-gatherers (EHGs), who later entered Scandinavia from the north along the Norwegian coast. During the Neolithic, they admixed further with Early European Farmers (EEFs) and Western Steppe Herders (WSHs). Genetic continuity has been detected between the SHGs and members of the Pitted Ware culture (PWC), and to a certain degree, between SHGs and modern northern Europeans. The Sámi, on the other hand, have been found to be completely unrelated to the PWC.

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the turn of the 5th millennium BC, subsequently detected in several genetically similar or directly related ancient populations including the Khvalynsk, Repin, Sredny Stog, and Yamnaya cultures, and found in substantial levels in contemporary European, Central Asian, South Asian and West Asian populations. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry, Yamnaya-related ancestry, Steppe ancestry or Steppe-related ancestry.

The Brushed Pottery culture was a European Bronze Age archaeological culture found in present-day eastern Lithuania, Belarus, and southeastern Latvia. It succeeded the Neolithic Narva culture. It got its name from its characteristic flat-bottomed pottery, the outer surface of which is generally brushed with strokes, believed to be applied with bundles of straw or grass during pottery making.

Yuzhny Oleny, also Yuzhniy Oleniy, is an archaeological site located on Yuzhny Oleny island, in Lake Onega, Karelia.