A wheel is a rotating component that is intended to turn on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be moved easily facilitating movement or transportation while supporting a load, or performing labor in machines. Wheels are also used for other purposes, such as a ship's wheel, steering wheel, potter's wheel, and flywheel.

The 3rd millennium BC spanned the years 3000 to 2001 BC. This period of time corresponds to the Early to Middle Bronze Age, characterized by the early empires in the Ancient Near East. In Ancient Egypt, the Early Dynastic Period is followed by the Old Kingdom. In Mesopotamia, the Early Dynastic Period is followed by the Akkadian Empire. In what is now Northwest India and Pakistan, the Indus Valley civilization developed a state society.

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history.

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 1950–1880 BCE and are depicted on cylinder seals from Central Anatolia in Kültepe dated to c. 1900 BCE. The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots was the spoked wheel.

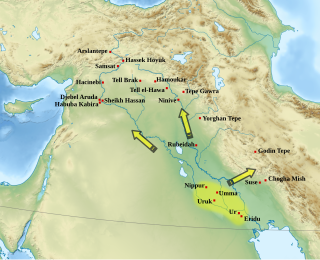

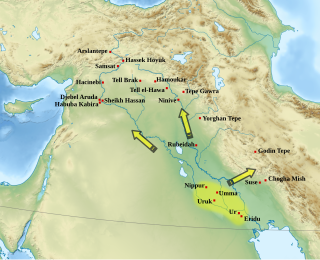

The 35th century BC in the Near East sees the gradual transition from the Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Proto-writing enters transitional stage, developing towards writing proper. Wheeled vehicles are now known beyond Mesopotamia, having spread north of the Caucasus and to Europe.

During the 40th century BC, the Eastern Mediterranean region was in the Chalcolithic period, transitional between the Stone and the Bronze Ages. Northwestern Europe was in the Neolithic. China was dominated by the Neolithic Yangshao culture. The Americas were in a phase of transition between the Paleo-Indian (Lithic) to the Meso-Indian (Archaic) stage. This century started in 4000 BC and ended in 3901 BC.

The Vinča symbols are a set of undeciphered symbols found on artifacts from the Neolithic Vinča culture and other "Old European" cultures of Central and Southeast Europe. Whether this is one of the earliest writing systems or simply symbols of some sort is disputed. They have sometimes been described as an example of proto-writing. The symbols went out of use around 3500 BC.

The Ubaid period is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK, was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe. It developed as a technological merger of local neolithic and mesolithic techno-complexes between the lower Elbe and middle Vistula rivers. These predecessors were the (Danubian) Lengyel-influenced Stroke-ornamented ware culture (STK) groups/Late Lengyel and Baden-Boleráz in the southeast, Rössen groups in the southwest and the Ertebølle-Ellerbek groups in the north. The TRB introduced farming and husbandry as major food sources to the pottery-using hunter-gatherers north of this line.

The wheel and axle is a simple machine consisting of a wheel attached to a smaller axle so that these two parts rotate together in which a force is transferred from one to the other. The wheel and axle can be viewed as a version of the Lever, with a drive force applied tangentially to the perimeter of the wheel, and a load force applied to the axle supported in a bearing, which serves as a fulcrum.

The Uruk period existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it has also been described as the "Protoliterate period".

During the growth of the ancient civilizations, ancient technology was the result from advances in engineering in ancient times. These advances in the history of technology stimulated societies to adopt new ways of living and governance.

Melid, also known as Arslantepe, was an ancient city on the Tohma River, a tributary of the upper Euphrates rising in the Taurus Mountains. It has been identified with the modern archaeological site of Arslantepe near Malatya, Turkey.

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the Paleolithic and early Neolithic periods only parts of Upper Mesopotamia were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the Early Bronze Age, for which reason it is often called a cradle of civilization.

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases.

The Stone Age in the territory of present-day Poland is divided into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic eras. The Paleolithic extended from about 500,000 BCE to 8000 BCE. The Paleolithic is subdivided into periods, the Lower Paleolithic, 500,000 to 350,000 BCE, the Middle Paleolithic, 350,000 to 40,000 BCE, the Upper Paleolithic, 40,000 to 10,000 BCE, and the Final Paleolithic, 10,000 to 8000 BCE. The Mesolithic lasted from 8000 to 5500 BCE, and the Neolithic from 5500 to 2300 BCE. The Neolithic is subdivided into the Neolithic proper, 5500 to 2900 BCE, and the Copper Age, 2900 to 2300 BCE.

The Starčevo–Karanovo I-II–Körös culture or Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture is a grouping of two related Neolithic archaeological cultures in Southeastern Europe: the Starčevo culture and the Körös or Criș culture.

The Leyla-Tepe culture of the South Caucasus belongs to the Chalcolithic era. It got its name from the site in the Agdam District of modern-day Azerbaijan. Its settlements were distributed on the southern slopes of Central Caucasus, from 4350 until 4000 B.C.

Başur Höyük in Turkey's south-eastern Siirt Province is a 5,000-year-old Bronze Age burial site. It is located near the village of Aktaş, Siirt in a valley of the upper Tigris River. The 820-foot by 492-foot burial mound was excavated in the years up to 2018, by Brenna Hassett of the Natural History Museum in London, and Haluk Sağlamtimur of Ege University in Turkey.

Jebel Aruda, is an ancient Near East archaeological site on the west bank of the Euphrates river in Raqqa Governorate, Syria. It was excavated as part of a program of rescue excavation project for sites to be submerged by the creation of Lake Assad by the Tabqa Dam. The site was occupied in the Late Chalcolithic, during the late 4th millennium BC, specifically in the Uruk V period. It is on the opposite side of the lake from the Halafian site of Shams ed-Din Tannira and is within sight of the Uruk V site Habuba Kabira and thought to have been linked to it. The archaeological sites of Tell es-Sweyhat and Tell Hadidi are also nearby.