The Roman legion, the largest military unit of the Roman army, comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic and 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of the Roman Empire.

The onager was a Roman torsion powered siege engine. It is commonly depicted as a catapult with a bowl, bucket, or sling at the end of its throwing arm. The onager was first mentioned in 353 AD by Ammianus Marcellinus, who described onagers as the same as a scorpion. The onager is often confused with the later mangonel, a "traction trebuchet" that replaced torsion powered siege engines in the 6th century AD.

The Frumentarii were an ancient Roman military and secret police organization used as an intelligence agency. They began their history as a courier service and developed into an imperial spying agency. Their organization would also carry out assassinations. The frumentarii were headquartered in the Castra Peregrina and were run by the princeps peregrinorum. They were disbanded under the reign of Diocletian due to their poor reputation amongst the populace.

The speculatores, also known as the speculatores augusti or the exploratores, were an ancient Roman reconnaissance agency. They were part of the consularis and were used by the Roman military. The speculatores were headquartered in the Castra Peregrina.

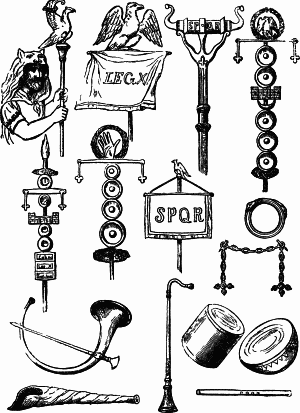

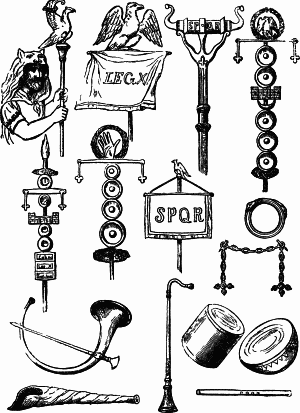

The Roman tuba, or trumpet was a military signal instrument used by the ancient Roman military and in religious rituals. They would signal troop movements such as retreating, attacking, or charging, as well as when guards should mount, sleep, or change posts. Thirty-six or thirty-eight tubicines were assigned to each Roman legion. The tuba would be blown twice each spring in military, governmental, or religious functions. This ceremony was known as the tubilustrium. It was also used in ancient Roman triumphs. It was considered a symbol of war and battle. The instrument was used by the Etruscans in their funerary rituals. It continued to be used in ancient Roman funerary practices.

Roman military personal equipment was produced in large numbers to established patterns, and used in an established manner. These standard patterns and uses were called the res militaris or disciplina. Its regular practice during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire led to military excellence and victory. The equipment gave the Romans a very distinct advantage over their barbarian enemies, especially so in the case of armour. This does not mean that every Roman soldier had better equipment than the richer men among his opponents. Roman equipment was not of a better quality than that used by the majority of Rome's adversaries. Other historians and writers have stated that the Roman army's need for large quantities of "mass produced" equipment after the so-called "Marian Reforms" and subsequent civil wars led to a decline in the quality of Roman equipment compared to the earlier Republican era:

The production of these kinds of helmets of Italic tradition decreased in quality because of the demands of equipping huge armies, especially during civil wars...The bad quality of these helmets is recorded by the sources describing how sometimes they were covered by wicker protections, like those of Pompeius' soldiers during the siege of Dyrrachium in 48 BC, which were seriously damaged by the missiles of Caesar's slingers and archers.

It would appear that armour quality suffered at times when mass production methods were being used to meet the increased demand which was very high the reduced size cuirasses would also have been quicker and cheaper to produce, which may have been a deciding factor at times of financial crisis, or where large bodies of men were required to be mobilized at short notice, possibly reflected in the poor-quality, mass produced iron helmets of Imperial Italic type C, as found, for example, in the River Po at Cremona, associated with the Civil Wars of AD 69 AD; Russell Robinson, 1975, 67

Up until then, the quality of helmets had been fairly consistent and the bowls well decorated and finished. However, after the Marian Reforms, with their resultant influx of the poorest citizens into the army, there must inevitably have been a massive demand for cheaper equipment, a situation which can only have been exacerbated by the Civil Wars...

The Cavarī or Cavarēs were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the western part of modern Vaucluse, around the present-day cities of Avignon, Orange and Cavaillon, during the Roman period. They were at the head of a confederation of tribes that included the Tricastini, Segovellauni and Memini, and whose territory stretched further north along the Rhône Valley up to the Isère river.

A galea was a Roman soldier's helmet. Some gladiators, specifically myrmillones, also wore bronze galeae with face masks and decorations, often a fish on its crest. The exact form or design of the helmet varied significantly over time, between differing unit types, and also between individual examples – pre-industrial production was by hand – so it is not certain to what degree there was any standardization even under the Roman Empire.

The Montefortino helmet was a type of Celtic, and later Roman, military helmet used from around 300 BC through the 1st century AD with continuing modifications. This helmet type is named after the region of Montefortino in Italy, where a Montefortino helmet was first uncovered in a Celtic burial. The Montefortino helmet originated in the 4th century BCE and was influenced by Etruscan and Celtic helmets. The helmet was brought to Italy by the Senones and it was the most popular helmet amongst the Roman army during the Republican period. The Montefortino helmet remained the most popular Roman helmet until the first century CE. Although in the Roman military it was replaced by the Coolus helmet, it continued to be used by the Praetorian guard.

The Imperial helmet-type was a type of helmet worn by Roman legionaries. Prior to the Empire, Roman Republican soldiers often provided their own equipment, which was passed down from father to son. Thus, a variety of equipment, from different eras was present in the ranks. Even as the professional Imperial army emerged, and short-term service citizen soldiers became rare, useful equipment was never discarded. So when the improved Imperial helmet appeared, it replaced what remained of the very old Coolus type, which was largely superseded at the time by improved versions of the Montefortino helmet type, which continued to serve alongside it for a time. This constituted the final evolutionary stage of the legionary helmet (galea).

The Coppergate Helmet is an eighth-century Anglo-Saxon helmet found in York, England. It was discovered in May 1982 during excavations for the Jorvik Viking Centre at the bottom of a pit that is thought to have once been a well.

The Phrygian helmet, also known as the Thracian helmet, was a type of helmet that originated in ancient Greece and was widely used in Thrace, Dacia, Magna Graecia and the Hellenistic world until well into the Roman Empire.

The Roman army of the late Republic refers to the armed forces deployed by the late Roman Republic, from the beginning of the first century BC until the establishment of the Imperial Roman army by Augustus in 30 BC.

The Waterloo Helmet is a pre-Roman Celtic bronze ceremonial horned helmet with repoussé decoration in the La Tène style, dating to circa 150–50 BC, that was found in 1868 in the River Thames by Waterloo Bridge in London, England. It is now on display at the British Museum in London.

The appearance of Celts in Western Romania can be traced to the later La Tène period . Excavation of the great La Tène necropolis at Apahida, Cluj County, by S. Kovacs at the turn of the 20th century revealed the first evidence of Celtic culture in Romania. The 3rd–2nd century BC site is remarkable for its cremation burials and chiefly wheel-made funeral vessels.

The Late Roman ridge helmet was a type of combat helmet of Late Antiquity used by soldiers of the Late Roman army. It was characterized by the possession of a bowl made up of two or four parts, united by a longitudinal ridge.

The Nijmegen Helmet is a Roman cavalry sports helmet from the first or second century AD. It was found around 1915 in a gravel bed on the left bank of the Waal river, near the Dutch city of Nijmegen. The helmet would have been worn by the élite Roman cavalry. The head portion of the helmet is made of iron, while the mask and diadem are of bronze or brass. The helmet provides neck protection via a projecting rim overlaid with a thin bronze covering plated with silver. The diadem features two male and three female figures.

The Agris Helmet is a ceremonial Celtic helmet from c. 350 BC that was found in a cave near Agris, Charente, France, in 1981. It is a masterpiece of Celtic art, and would probably have been used for display rather than worn in battle. The helmet consists of an iron cap completely covered with bands of bronze. The bronze is in turn covered with unusually pure gold leaf, with embedded coral decorations attached using silver rivets. One of the cheek guards was also found and has similar materials and designs. The helmet is mostly decorated in early Celtic patterns but there are later Celtic motifs and signs of Etruscan or Greek influence. The quality of the gold indicates that the helmet may well have been made locally in the Atlantic region.

The military nature of Mycenaean Greece in the Late Bronze Age is evident by the numerous weapons unearthed, warrior and combat representations in contemporary art, as well as by the preserved Greek Linear B records. The Mycenaeans invested in the development of military infrastructure with military production and logistics being supervised directly from the palatial centres. This militaristic ethos inspired later Ancient Greek tradition, and especially Homer's epics, which are focused on the heroic nature of the Mycenaean-era warrior élite.

The Witcham Gravel helmet is a Roman auxiliary cavalry helmet from the first century AD. Only the decorative copper alloy casing remains; an iron core originally fit under the casing, but has now corroded away. The cap, neck guard, and cheek guards were originally tinned, giving the appearance of a silver helmet encircled by a gold band. The helmet's distinctive feature is the presence of three hollow bosses, out of an original six, that decorate the exterior. No other Roman helmet is known to have such a feature. They may be a decorative embellishment influenced by Etruscan helmets from the sixth century BC, which had similar, lead-filled bosses, that would have deflected blades.