A hillfort is a type of fortified refuge or defended settlement located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typical of the late European Bronze Age and Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roman period. The fortification usually follows the contours of a hill and consists of one or more lines of earthworks or stone ramparts, with stockades or defensive walls, and external ditches. If enemies were approaching, the civilians would spot them from a distance.

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some have hook and ring closures and a few have mortice and tenon locking catches to close them. Many seem designed for near-permanent wear and would have been difficult to remove.

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period. Celtic paganism was one of a larger group of polytheistic Indo-European religions of Iron Age Europe.

Boa Island is an island near the north shore of Lower Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is 16 miles (26 km) from Enniskillen town. It is the largest island in Lough Erne, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) long, and relatively narrow. The A47 road goes through the length of the island and joins each end of the island to the mainland by bridges leading west toward Castle Caldwell and east toward Kesh.

The prehistory of Ireland has been pieced together from archaeological evidence, which has grown at an increasing rate over the last decades. It begins with the first evidence of permanent human residence in Ireland around 10,500 BC and finishes with the start of the historical record around 400 AD. Both the beginning and end dates of the period are later than for much of Europe and all of the Near East. The prehistoric period covers the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age societies of Ireland. For much of Europe, the historical record begins when the Romans invaded; as Ireland was not invaded by the Romans its historical record starts later, with the coming of Christianity.

Miranda Jane Aldhouse-Green, is a British archaeologist and academic, known for her research on the Iron Age and the Celts. She was Professor of Archaeology at Cardiff University from 2006 to 2013. Until about 2000, she published as Miranda Green or Miranda J. Green.

The National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology is a branch of the National Museum of Ireland located on Kildare Street in Dublin, Ireland, that specialises in Irish and other antiquities dating from the Stone Age to the Late Middle Ages.

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. While they were reported to have been literate, they are believed to have been prevented by doctrine from recording their knowledge in written form. Their beliefs and practices are attested in some detail by their contemporaries from other cultures, such as the Romans and the Greeks.

Prehistoric art in Scotland is visual art created or found within the modern borders of Scotland, before the departure of the Romans from southern and central Britain in the early fifth century CE, which is usually seen as the beginning of the early historic or Medieval era. There is no clear definition of prehistoric art among scholars and objects that may involve creativity often lack a context that would allow them to be understood.

The Broddenbjerg idol is a wooden ithyphallic figure found in a bog at Broddenbjerg, near Viborg, Denmark and now in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. It is dated to approximately 535–520 BCE.

Anthropomorphic wooden cult figurines, sometimes called pole gods, have been found at many archaeological sites in Central and Northern Europe. They are generally interpreted as cult images, in some cases presumably depicting deities, sometimes with either a votive or an apotropaic (protective) function. Many have been preserved in peat bogs. The majority are more or less crudely worked poles or forked sticks; some take the form of carved planks. They have been dated to periods from the Mesolithic to the Early Middle Ages, including the Roman Era and the Migration Age. The majority have been found in areas of Germanic settlement, but some are from areas of Celtic settlement and from the later part of the date range, Slavic settlement. A typology has been developed based on the large number found at Oberdorla, Thuringia, at a sacrificial bog which is now the Opfermoor Vogtei open-air museum.

The Ralaghan idol, also known as the "Ralaghan figure", is a late Bronze Age anthropomorphic, carved wooden figure found in a bog in the townland of Ralaghan, County Cavan, Ireland. It is held by the National Museum of Ireland.

The Inneenboy cross or the Roughan Hill Tau Cross is a stone tau cross located in County Clare, Ireland. It is a National Monument.

The Tandragee Idol is the name given to a carved sandstone figure, generally dated to the Iron Age, with some sources suggesting a date as early as 1,000 BC. The sculpture was found in the 19th century in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It is 60 cm (24 in) in height, and consists of the torso and head of a grotesque and brutish-looking figure who crosses his body with his left arm to hold his right arm in what appears to be a ritualistic pose. The idol has a crude, vulgar and gaping mouth, pierced nostrils and the stubs of a horned helmet.

Thomas J. Barron, known as Tom, was an Irish folklorist and amateur historian. A primary school teacher by profession, Barron became respected through extensive local field research, conservation efforts, and his regular contributions to the Irish Folklore Commission, with articles largely gathering and detailing the folklore of the East Cavan area.

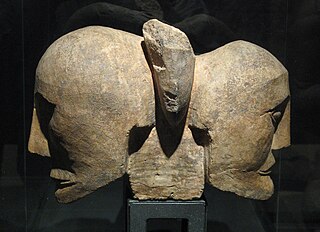

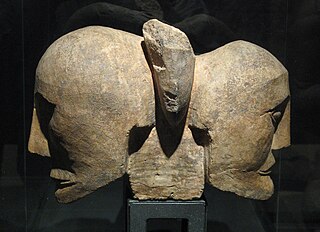

The Corraghy Heads was the name given to two physically connected Iron Age stone idols uncovered c. 1855 in the townland of Drumeague, County Cavan, Ireland. The sculpture consisted of a two-headed or double idol janus structure of a human and ram's head linked by a long cross-piece. The ram's head was lost in the mid-19th century, but the human head survives and is now in the National Museum of Ireland, but is rarely displayed. This head is unusually naturalistic for the time, having ears, hair and a beard.

The Pfalzfeld obelisk is a Celtic carved sandstone monument, an example of the sculpture of the Iron Age La Tène culture. The obelisk, removed from its original site to the churchyard of Pfalzfeld, is believed to have been a funerary monument from one of the nearby burial grounds. The obelisk has been dated to the 4th or 5th century BC. It is currently in the collection of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn.

The Holzgerlingen figure is a two-faced anthropomorphic statue of the early to middle La Tène culture. The statue depicts a human figure from the belt up, each side carved with a mirror image of the other, wearing a horn-like headdress which is probably an example of the Celtic leaf-crown motif. The figure is thought to be a Celtic cult object, perhaps representing a god, though it is less often identified as a funerary monument. Over 2 metres tall, the Holzgerlingen figure is the largest known Iron Age statue. The statue is presently at the Landesmuseum Württemberg.

The Euffigneix statue or God of Euffigneix is a Celtic stone pillar statue found near Euffigneix, a commune of Haute-Marne, France. The statue has been dated to the 1st century BC, within the Gallo-Roman period. The statue is a human bust with a large relief of a boar on its chest. The boar was a potent symbol for the Celts and the figure has been thought to represent a Gaulish boar-god, perhaps Moccus.

Celtic stone idols are Northern European stone sculptures dated to the Iron Age, that are believed to represent Celtic gods. The majority contain one or more human heads, which may have one or more faces. It is thought that the heads were often placed on top of pillar stones and were a centrepiece at cultic worship sites. They can be found across Northern Europe but are most numerous in Gaul and the British Isles, with the majority dating to the Romano-British and Gallo-Roman periods. Thus, they are sometimes described as a result of cultural exchange between abstract Celtic art and the Roman tradition of monumental stone carving. Parallels are found in contemporary Scandinavia.