A Movie is a 1958 experimental collage film by American artist Bruce Conner. It combines pieces of found footage taken from various sources such as newsreels, soft-core pornography, and B movies, all set to a score featuring Ottorino Respighi's Pines of Rome.

An underground film is a film that is out of the mainstream either in its style, genre or financing.

Experimental film or avant-garde cinema is a mode of filmmaking that rigorously re-evaluates cinematic conventions and explores non-narrative forms or alternatives to traditional narratives or methods of working. Many experimental films, particularly early ones, relate to arts in other disciplines: painting, dance, literature and poetry, or arise from research and development of new technical resources.

Lawrence Jordan is an American independent filmmaker who is most widely known for his animated collage films. He was a founding member of the Canyon Cinema Cooperative and the Camera Obscura Film Society.

Structural film was an avant-garde experimental film movement prominent in the United States in the 1960s. A related movement developed in the United Kingdom in the 1970s.

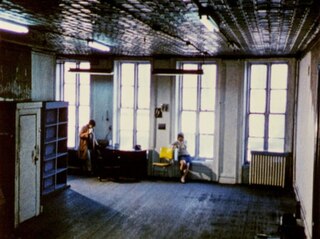

Wavelength is a 1967 experimental film by Canadian artist Michael Snow. Shot from a fixed camera angle, it depicts a loft space with an extended zoom over the duration of the film. Considered a landmark of avant-garde cinema, it was filmed over one week in December 1966 and edited in 1967, and is an example of what film theorist P. Adams Sitney describes as "structural film", calling Snow "the dean of structural filmmakers."

Nathaniel Dorsky is an American experimental filmmaker and film editor. His film career began during the New American Cinema movement of the 1960s, when he met his partner Jerome Hiler. He won an Emmy Award in 1967 for his work on the film Gauguin in Tahiti: Search for Paradise.

Venom and Eternity is a 1951 French avant-garde film by Isidore Isou that grew out of the Lettrist movement in Paris. It created a scandal at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival.

Schwechater is a 1958 experimental short film by Austrian filmmaker Peter Kubelka. It is the second entry in his trilogy of metrical films, between Adebar and Arnulf Rainer.

The End is a 1953 American short film directed by Christopher Maclaine. It tells the stories of six people on the last day of their lives. It premiered at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art as part of Frank Stauffacher's Art in Cinema series. Though the film met audience disapproval at its premiere, it was praised by critics as a "masterpiece" and "a great work of art".

All My Life is a 1966 American experimental short film directed by Bruce Baillie. It shows a continuous shot of a fence, soundtracked by Ella Fitzgerald's 1936 debut single "All My Life". Film critic P. Adams Sitney identified it as an early example of what he termed structural film.

Anticipation of the Night is a 1958 American avant-garde film directed by Stan Brakhage. It was a breakthrough in the development of the lyrical style Brakhage used in his later films.

Variations is a 1998 American short silent avant-garde film directed by Nathaniel Dorsky. It is the second film in a set of "Four Cinematic Songs", which also includes Triste, Arbor Vitae, and Love's Refrain.

Side/Walk/Shuttle is a 1991 American avant-garde film directed by Ernie Gehr. It shows downtown San Francisco as seen at different angles from a moving elevator.

Adebar is a 1957 Austrian avant-garde short film directed by Peter Kubelka. It is the first entry in Kubelka's trilogy of metrical films, followed by Schwechater and Arnulf Rainer. Adebar is the first film to be edited entirely according to a mathematical rhythmic strategy.

Triste is a 1996 American avant-garde short film directed by Nathaniel Dorsky. It is the first in a set of "Four Cinematic Songs", which also includes Variations, Arbor Vitae, and Love's Refrain.

Breakaway is a 1966 American short film by Bruce Conner. It shows Toni Basil dancing to her song "Breakaway". The film has a palindromic structure in which the second half of the film reverses the image and sound of the first half. Breakaway is often cited as a precursor to the development of the music video.

The Way to Shadow Garden is a 1955 American experimental film directed by Stan Brakhage.

Twice a Man is a 1963 American avant-garde film directed by Gregory Markopoulos.

Eniaios is a 22-part silent avant-garde film by Gregory Markopoulos, completed in 1991 and released in parts starting in 2004. The film is made from previous released and unreleased films by Markopoulos, arranged into 22 orders totaling 80 hours of footage. An extensive restoration effort on the film began several years after Markopoulos's death in 1992, and as prints of each order have been created, they have been presented in an ongoing premiere, taking place every four years at a remote site near Lyssarea, Greece.