Cryptosporidiosis, sometimes informally called crypto, is a parasitic disease caused by Cryptosporidium, a genus of protozoan parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa. It affects the distal small intestine and can affect the respiratory tract in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, resulting in watery diarrhea with or without an unexplained cough. In immunosuppressed individuals, the symptoms are particularly severe and can be fatal. It is primarily spread through the fecal-oral route, often through contaminated water; recent evidence suggests that it can also be transmitted via fomites contaminated with respiratory secretions.

Isosporiasis, also known as cystoisosporiasis, is a human intestinal disease caused by the parasite Cystoisospora belli. It is found worldwide, especially in tropical and subtropical areas. Infection often occurs in immuno-compromised individuals, notably AIDS patients, and outbreaks have been reported in institutionalized groups in the United States. The first documented case was in 1915. It is usually spread indirectly, normally through contaminated food or water (CDC.gov).

Coccidia (Coccidiasina) are a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class Conoidasida. As obligate intracellular parasites, they must live and reproduce within an animal cell. Coccidian parasites infect the intestinal tracts of animals, and are the largest group of apicomplexan protozoa.

Coccidiosis is a parasitic disease of the intestinal tract of animals caused by coccidian protozoa. The disease spreads from one animal to another by contact with infected feces or ingestion of infected tissue. Diarrhea, which may become bloody in severe cases, is the primary symptom. Most animals infected with coccidia are asymptomatic, but young or immunocompromised animals may suffer severe symptoms and death.

Eimeria is a genus of apicomplexan parasites that includes various species capable of causing the disease coccidiosis in animals such as cattle, poultry and smaller ruminants including sheep and goats. Eimeria species are considered to be monoxenous because the life cycle is completed within a single host, and stenoxenous because they tend to be host specific, although a number of exceptions have been identified. Species of this genus infect a wide variety of hosts. Thirty-one species are known to occur in bats (Chiroptera), two in turtles, and 130 named species infect fish. Two species infect seals. Five species infect llamas and alpacas: E. alpacae, E. ivitaensis, E. lamae, E. macusaniensis, and E. punonensis. A number of species infect rodents, including E. couesii, E. kinsellai, E. palustris, E. ojastii and E. oryzomysi. Others infect poultry, rabbits and cattle. For full species list, see below.

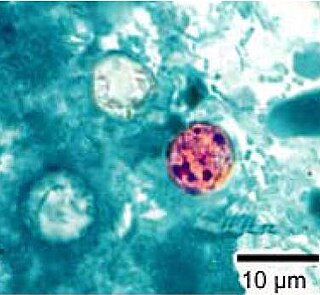

Cryptosporidium parvum is one of several species that cause cryptosporidiosis, a parasitic disease of the mammalian intestinal tract.

Cryptosporidium, sometimes called crypto, is an apicomplexan genus of alveolates which are parasites that can cause a respiratory and gastrointestinal illness (cryptosporidiosis) that primarily involves watery diarrhea, sometimes with a persistent cough.

Plasmodium knowlesi is a parasite that causes malaria in humans and other primates. It is found throughout Southeast Asia, and is the most common cause of human malaria in Malaysia. Like other Plasmodium species, P. knowlesi has a life cycle that requires infection of both a mosquito and a warm-blooded host. While the natural warm-blooded hosts of P. knowlesi are likely various Old World monkeys, humans can be infected by P. knowlesi if they are fed upon by infected mosquitoes. P. knowlesi is a eukaryote in the phylum Apicomplexa, genus Plasmodium, and subgenus Plasmodium. It is most closely related to the human parasite Plasmodium vivax as well as other Plasmodium species that infect non-human primates.

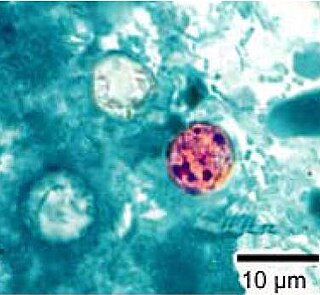

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a coccidian parasite that causes a diarrheal disease called cyclosporiasis in humans and possibly in other primates. Originally reported as a novel pathogen of probable coccidian nature in the 1980s and described in the early 1990s, it was virtually unknown in developed countries until awareness increased due to several outbreaks linked with fecally contaminated imported produce. C. cayetanensis has since emerged as an endemic cause of diarrheal disease in tropical countries and a cause of traveler's diarrhea and food-borne infections in developed nations. This species was placed in the genus Cyclospora because of the spherical shape of its sporocysts. The specific name refers to the Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru, where early epidemiological and taxonomic work was done.

The 1993 Milwaukee cryptosporidiosis outbreak was a significant distribution of the Cryptosporidium protozoan in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the largest waterborne disease outbreak in documented United States history. It is suspected that The Howard Avenue Water Purification Plant, one of two water treatment plants in Milwaukee at the time, was contaminated. It is believed that the contamination was due to an ineffective filtration process. Approximately 403,000 residents were affected resulting in illness and hospitalization. Immediate repairs were made to the treatment facilities along with continued infrastructure upgrades during the 25 years since the outbreak. The total cost of the outbreak, in productivity loss and medical expenses, was $96 million. At least 69 people died as a result of the outbreak. The city of Milwaukee has spent upwards to $510 million in repairs, upgrades, and outreach to citizens.

Sarcocystis is a genus of protozoan parasites, with many species infecting mammals, reptiles and birds. Its name is dervived from Greek sarx = flesh and kystis = bladder.

Nitazoxanide, sold under the brand name Alinia among others, is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic and broad-spectrum antiviral medication that is used in medicine for the treatment of various helminthic, protozoal, and viral infections. It is indicated for the treatment of infection by Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in immunocompetent individuals and has been repurposed for the treatment of influenza. Nitazoxanide has also been shown to have in vitro antiparasitic activity and clinical treatment efficacy for infections caused by other protozoa and helminths; evidence as of 2014 suggested that it possesses efficacy in treating a number of viral infections as well.

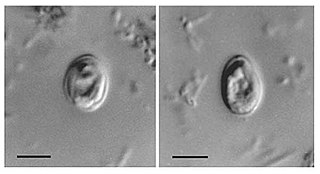

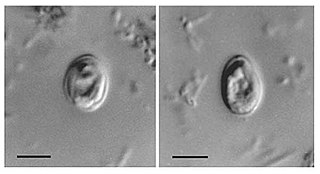

Blastocystis is a genus of single-celled parasites belonging to the Stramenopiles that includes algae, diatoms, and water molds. There are several species, living in the gastrointestinal tracts of species as diverse as humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and cockroaches. Blastocystis has low host specificity, and many different species of Blastocystis can infect humans, and by current convention, any of these species would be identified as Blastocystis hominis.

Blastocystosis refers to a medical condition caused by infection with Blastocystis. Blastocystis is a protozoal, single-celled parasite that inhabits the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other animals. Many different types of Blastocystis exist, and they can infect humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and even cockroaches. Blastocystosis has been found to be a possible risk factor for development of irritable bowel syndrome.

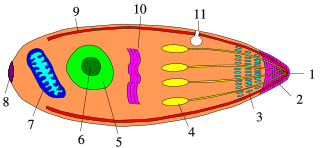

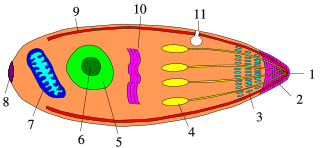

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is typified by a cellular variety with a distinct morphology and biochemistry.

Cryptosporidium muris is a species of coccidium, first isolated from the gastric glands of the common mouse. Cryptosporidium does originate in common mice, specifically laboratory mice. However, it also has infected cows, dogs, cats, rats, rabbits, lambs, and humans and other primates.

Cystoisospora belli, previously known as Isospora belli, is a parasite that causes an intestinal disease known as cystoisosporiasis. This protozoan parasite is opportunistic in immune suppressed human hosts. It primarily exists in the epithelial cells of the small intestine, and develops in the cell cytoplasm. The distribution of this coccidian parasite is cosmopolitan, but is mainly found in tropical and subtropical areas of the world such as the Caribbean, Central and S. America, India, Africa, and S.E. Asia. In the U.S., it is usually associated with HIV infection and institutional living.

Cryspovirus is a genus of viruses, in the family Partitiviridae. Protists serve as natural hosts. There is only one species in this genus: Cryptosporidium parvum virus 1.

Cryptosporidium varanii is a protozoal parasite that infects the gastrointestinal tract of lizards. C. varanii is often shed in the feces, and transmission is primarily via fecal-oral route. Unlike Cryptosporidium serpentis, C. varanii does not colonize the stomach, but rather the intestines of most infected lizards, such as geckos. An exception to this rule are monitor lizards, as gastric (stomach) lesions have been found in those species. Oocysts of lizard Cryptosporidium are larger than the snake counterpart.

Cryptosporidium serpentis is a protozoal parasite that infects the gastrointestinal tract of snakes. Sporated oocysts of C. serpentis are intermittently shed in the feces, and transmission is primarily via fecal-oral route. C. serpentis is a gastric parasite, primarily colonizing the stomach. Unlike mammalian Cryptosporidium - that is usually self-limiting - C. serpentis remains chronic and in most cases, eventually lethal in snakes once an animal has become symptomatic. However, recent advancements in detection have led to the identification of healthy carrier animals some of which have thus far remained in good health for years and cast doubt on previous assumptions about the lethality of the parasite, though it remains to be seen how many carriers will remain healthy and for how long as most such animals are euthanized immediately. Cryptosporidiosis infection has been documented in a variety of snake species worldwide, such as North American Corn snakes and Australian Taipans, both free-living and captive. Necropsy examinations of expired captive snakes infected with C. serpentis note characteristic gastric mucosal hypertrophy that, in time, narrows the gastric lumen, resulting in classic symptoms of repetitive regurgitation and anorexia. Due to the enlargement of the stomach lining, a noticeable midbody bulge can be palpable and commonly visible. Frequent mucoid stools have been reported. However, some snakes will display no external symptoms at all throughout their lifetime, yet still remain infectious to counterparts.