Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne disease of dogs usually caused by the rickettsial agent Ehrlichia canis. Ehrlichia canis is the pathogen of animals. Humans can become infected by E. canis and other species after tick exposure. German Shepherd Dogs are thought to be susceptible to a particularly severe form of the disease; other breeds generally have milder clinical signs. Cats can also be infected.

Babesiosis or piroplasmosis is a malaria-like parasitic disease caused by infection with a eukaryotic parasite in the order Piroplasmida, typically a Babesia or Theileria, in the phylum Apicomplexa. Human babesiosis transmission via tick bite is most common in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States and parts of Europe, and sporadic throughout the rest of the world. It occurs in warm weather. People can get infected with Babesia parasites by the bite of an infected tick, by getting a blood transfusion from an infected donor of blood products, or by congenital transmission . Ticks transmit the human strain of babesiosis, so it often presents with other tick-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease. After trypanosomes, Babesia is thought to be the second-most common blood parasite of mammals. They can have major adverse effects on the health of domestic animals in areas without severe winters. In cattle, the disease is known as Texas cattle fever or redwater.

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is a retrovirus that infects cats. FeLV can be transmitted from infected cats when the transfer of saliva or nasal secretions is involved. If not defeated by the animal's immune system, the virus weakens the cat's immune system, which can lead to diseases which can be lethal. Because FeLV is cat-to-cat contagious, FeLV+ cats should only live with other FeLV+ cats.

Tick-borne diseases, which afflict humans and other animals, are caused by infectious agents transmitted by tick bites. They are caused by infection with a variety of pathogens, including rickettsia and other types of bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. The economic impact of tick-borne diseases is considered to be substantial in humans, and tick-borne diseases are estimated to affect ~80 % of cattle worldwide. Most of these pathogens require passage through vertebrate hosts as part of their life cycle. Tick-borne infections in humans, farm animals, and companion animals are primarily associated with wildlife animal reservoirs. Many tick-borne infections in humans involve a complex cycle between wildlife animal reservoirs and tick vectors. The survival and transmission of these tick-borne viruses are closely linked to their interactions with tick vectors and host cells. These viruses are classified into different families, including Asfarviridae, Reoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Bunyaviridae, and Flaviviridae.

A trophozoite is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of certain protozoa such as malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum and those of the Giardia group. The complementary form of the trophozoite state is the thick-walled cyst form. They are often different from the cyst stage, which is a protective, dormant form of the protozoa. Trophozoites are often found in the host's body fluids and tissues and in many cases, they are the form of the protozoan that causes disease in the host. In the protozoan, Entamoeba histolytica it invades the intestinal mucosa of its host, causing dysentery, which aid in the trophozoites traveling to the liver and leading to the production of hepatic abscesses.

Atovaquone, sold under the brand name Mepron, is an antimicrobial medication for the prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP).

Bartonellosis is an infectious disease produced by bacteria of the genus Bartonella. Bartonella species cause diseases such as Carrión's disease, trench fever, cat-scratch disease, bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatis, chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, chronic lymphadenopathy, and neurological disorders.

Chlamydia felis is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen that infects cats. It is endemic among domestic cats worldwide, primarily causing inflammation of feline conjunctiva, rhinitis and respiratory problems. C. felis can be recovered from the stomach and reproductive tract. Zoonotic infection of humans with C. felis has been reported. Strains FP Pring and FP Cello have an extrachromosomal plasmid, whereas the FP Baker strain does not. FP Cello produces lethal disease in mice, whereas the FP Baker does not. An attenuated FP Baker strain, and an attenuated 905 strain, are used as live vaccines for cats.

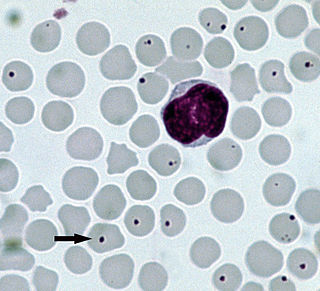

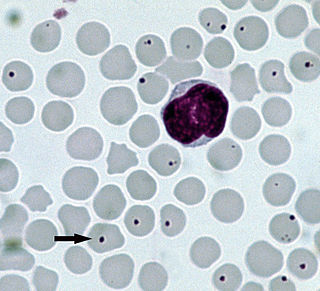

Babesia, also called Nuttallia, is an apicomplexan parasite that infects red blood cells and is transmitted by ticks. Originally discovered by the Romanian bacteriologist Victor Babeș in 1888, over 100 species of Babesia have since been identified.

Anaplasmosis is a tick-borne disease affecting ruminants, dogs, and horses, and is caused by Anaplasma bacteria. Anaplasmosis is an infectious but not contagious disease. Anaplasmosis can be transmitted through mechanical and biological vector processes. Anaplasmosis can also be referred to as "yellow bag" or "yellow fever" because the infected animal can develop a jaundiced look. Other signs of infection include weight loss, diarrhea, paleness of the skin, aggressive behavior, and high fever.

Babesia microti is a parasitic blood-borne piroplasm transmitted by deer ticks. B. microti is responsible for the disease babesiosis, a malaria-like disease which also causes fever and hemolysis.

Tropical theileriosis or Mediterranean theileriosis is a theileriosis of cattle from the Mediterranean and Middle East area, from Morocco to Western parts of India and China. It is a tick-borne disease, caused by Theileria annulata. The vectors are ticks of the genera Hyalomma and Rhipicephalus.

Ehrlichia canis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that acts as the causative agent of ehrlichiosis, a disease most commonly affecting canine species. This pathogen is present throughout the United States, South America, Asia, Africa and recently in the Kimberley region of Australia. First defined in 1935, E. canis emerged in the United States in 1963 and its presence has since been found in all 48 contiguous United States. Reported primarily in dogs, E. canis has also been documented in felines and humans, where it is transferred most commonly via Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick.

Theileria parva is a species of parasites, named in honour of Arnold Theiler, that causes East Coast fever (theileriosis) in cattle, a costly disease in Africa. The main vector for T. parva is the tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Theiler found that East Coast fever was not the same as redwater, but caused by a different protozoan.

Cat-scratch disease (CSD) is an infectious disease that most often results from a scratch or bite of a cat. Symptoms typically include a non-painful bump or blister at the site of injury and painful and swollen lymph nodes. People may feel tired, have a headache, or a fever. Symptoms typically begin within 3–14 days following infection.

Mycoplasma haemofelis is a gram-negative epierythrocytic parasitic bacterium. It often appears in bloodsmears as small (0.6μm) coccoid bodies, sometimes forming short chains of three to eight organisms. It is usually the causative agent of feline infectious anemia (FIA) in the United States.

Ticks of domestic animals directly cause poor health and loss of production to their hosts. Ticks also transmit numerous kinds of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa between domestic animals. These microbes cause diseases which can be severely debilitating or fatal to domestic animals, and may also affect humans. Ticks are especially important to domestic animals in tropical and subtropical countries, where the warm climate enables many species to flourish. Also, the large populations of wild animals in warm countries provide a reservoir of ticks and infective microbes that spread to domestic animals. Farmers of livestock animals use many methods to control ticks, and related treatments are used to reduce infestation of companion animals.

Cytauxzoon is a genus of parasitic alveolates in the phylum Apicomplexa. The name is derived from the Greek meaning an increase in the number of cells in an animal.

Anaplasma bovis is gram negative, obligate intracellular organism, which can be found in wild and domestic ruminants, and potentially a wide variety of other species. It is one of the last species of the Family Anaplasmaceae to be formally described. It preferentially infects host monocytes, and is often diagnosed via blood smears, PCR, and ELISA. A. bovis is not currently considered zoonotic, and does not frequently cause serious clinical disease in its host. This organism is transmitted by tick vectors, so tick bite prevention is the mainstay of A. bovis control, although clinical infections can be treated with tetracyclines. This organism has a global distribution, with infections noted in many areas, including Korea, Japan, Europe, Brazil, Africa, and North America.

Babesia canis is a parasite that infects red blood cells and can lead to anemia. This is a species that falls under the overarching genus Babesia. It is transmitted by the brown dog tick and is one of the most common piroplasm infections. The brown dog tick is adapted to warmer climates and is found in both Europe and the United States, especially in shelters and greyhound kennels. In Europe, it is also transmitted by Dermacentor ticks with an increase in infections reported due to people traveling with their pets.