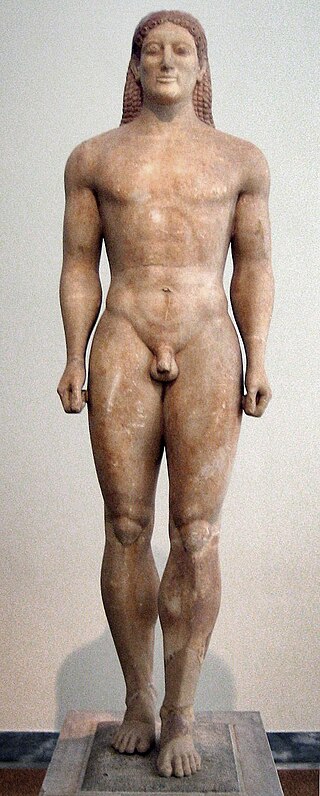

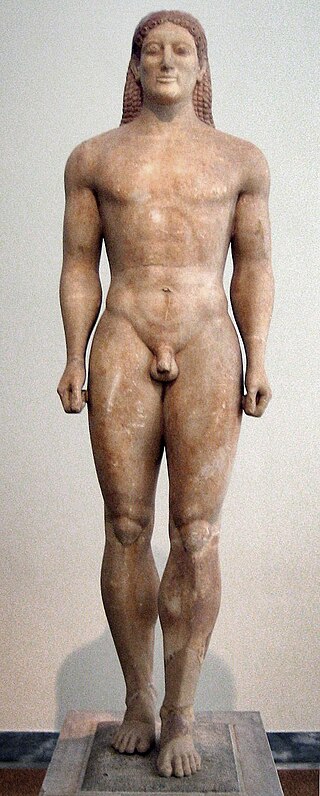

Kouros is the modern term given to free-standing Ancient Greek sculptures that depict nude male youths. They first appear in the Archaic period in Greece and are prominent in Attica and Boeotia, with a less frequent presence in many other Ancient Greek territories such as Sicily. Such statues are found across the Greek-speaking world; the preponderance of these were found in sanctuaries of Apollo with more than one hundred from the sanctuary of Apollo Ptoion, Boeotia, alone. These free-standing sculptures were typically marble, but the form is also rendered in limestone, wood, bronze, ivory and terracotta. They are typically life-sized, though early colossal examples are up to 3 meters tall.

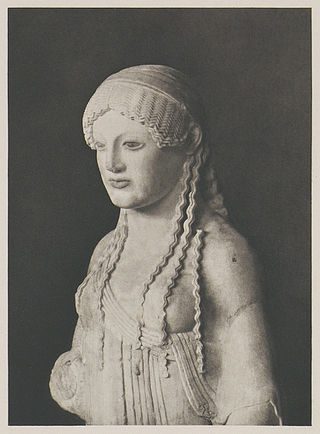

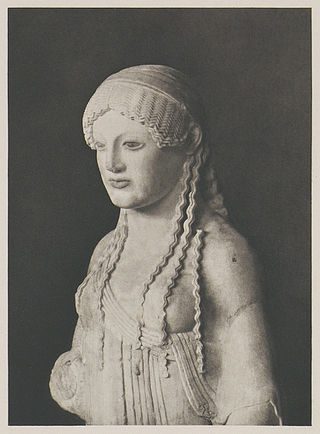

The relatively small limestone Cretan sculpture called the Lady of Auxerre, at the Louvre Museum in Paris depicts an archaic Greek goddess of c. 650 - 625 BCE. It is a Kore ("maiden"), perhaps a votary rather than the maiden Goddess Persephone herself, for her right hand touches her solar plexus and her left remains stiffly at her side. It is also possible that the Kore is a depiction of a deceased individual, possibly in a position of prayer.

The daidala is a type of sculpture attributed to the legendary Greek artist Daedalus, who is connected in legend both to Bronze Age Crete and to the earliest period of Archaic sculpture in Bronze Age Greece. The legends about Daedalus recognize him both as a man and as a mythical embodiment. He was the reputed inventor of agalmata, statues of the gods which had open eyes and moveable limbs. These statues were so lifelike that Plato remarked upon their amazing and disconcerting mobility, which was accomplished with techniques that are clearly those of the "daidala". The writer Pausanias thought that wooden images were referred to as "daidala" even before Daedalus’s time. The name "Daedalus", more specifically, has been suggested by Alberto Pérez-Gómez to be a play on the Greek word "daidala" which appears in archaic literature as a complement of the verb "to make", "to manufacture", "to forge", "to weave", "to place on", or "to see". Daidala were the implements of early society: defensive works, arms, furniture, and so forth.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from c. 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea: by the end of the period, they were part of a trade network that spanned the entire Mediterranean.

The Heraion of Samos was a large sanctuary to the goddess Hera, on the island of Samos, Greece, 6 km southwest of the ancient city of Samos. It was located in the low, marshy basin of the Imbrasos river, near where it enters the sea. The late Archaic temple in the sanctuary was the first of the gigantic free-standing Ionic temples, but its predecessors at this site reached back to the Geometric Period of the 8th century BC, or earlier. The ruins of the temple, along with the nearby archeological site of Pythagoreion, were designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1992, as a testimony to their exceptional architecture and to the mercantile and naval power of Samos during the Archaic Period.

Prinias is an archaeological site in Crete that has revealed a seventh-century BCE temple with striking similarities to ancient Egyptian architecture, including an Egyptianised seated goddess. It is 35 kilometres (22 mi) southwest of Iraklion, about halfway between Gortyn and Knossos. Above the site is a peak sanctuary, a sub-Minoan survival.

The Artemision Bronze is an ancient Greek sculpture that was recovered from the sea off Cape Artemision, in northern Euboea, Greece. According to most scholars, the bronze represents Zeus, the thunder-god and king of gods, though it has also been suggested it might represent Poseidon. The statue is slightly over lifesize at 2.09 meters, and would have held either a thunderbolt, if Zeus, or a trident if Poseidon. The empty eye-sockets were originally inset, probably with bone, as well as the eyebrows, the lips, and the nipples. The sculptor is unknown. The statue is a highlight of the collections in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

For the Apollo Temple in the Grand Canyon, see Apollo Temple.

Kore is the modern term given to a type of free-standing ancient Greek sculpture of the Archaic period depicting female figures, always of a young age. Kouroi are the youthful male equivalent of kore statues.

Delphi Archaeological museum is one of the principal museums of Greece and one of the most visited. It is operated by the Greek Ministry of Culture. Founded in 1903, it has been rearranged several times and houses the discoveries made at the Panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi, which date from the Late Helladic (Mycenean) period to the early Byzantine era.

The Sounion Kouros is an early archaic Greek statue of a naked young man or kouros carved in marble from the island of Naxos around 600 BCE. It is one of the earliest examples that scholars have of the kouros-type which functioned as votive offerings to gods or demi-gods, and were dedicated to heroes. Found near the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion, this kouros was found badly damaged and heavily weathered. It was restored to its original height of 3.05 meters (10.0 ft) returning it to its larger than life size. It is now held by the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The Phrasikleia Kore is an Archaic Greek funerary statue by the artist Aristion of Paros, created between 550 and 540 BCE. It was found carefully buried in the ancient city of Myrrhinous in Attica and excavated in 1972. The exceptional preservation of the statue and the intact nature of the polychromy elements makes the Phrasikleia Kore one of the most important works of Archaic art.

The Xenokrateia Relief is a marble votive offering, dated to the end of the fifth-century BCE. It commemorates the foundation of a sanctuary to the river god Kephisos by a woman named Xenokrateia.

Piraeus Artemis refers to two bronze statues of Artemis excavated in Piraeus, Athens in 1959, along with a large theatrical mask and three pieces of marble sculptures. Two other statues were found in the buried cache as well: a larger-than-lifesize bronze archaistic Apollo ostensibly from late fourth century, and a similarly sized bronze fourth century-style Athena. Both statues are now exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus in Athens.

The Peplos Kore is an ancient sculpture from the Acropolis of Athens. It is considered one of the best-known examples of Archaic Greek art. Kore is a type of archaic Greek statue that portrays a young woman with a stiff posture looking straight forward. Although this statue is one of the most famous examples of a kore, it is actually not considered a typical one. The statue is not completely straight, her face is leaned slightly to the side, and she is standing with her weight shifted to one leg. The other part of the statue's name, peplos, is based on the popular archaic Greek gown for women. When the statue was found it was initially thought that she was wearing a peplos, although it is now known that she is not.

The Antenor Kore is a Late Archaic statue of a girl (Kore) made of Parian marble, which was created around 530/20 BC.

The Euthydikos Kore is a late archaic, Parian marble statue of the kore type, c 490–480 BCE, that once stood amongst the Akropolis votive sculptures. It was destroyed during the Persian invasion of 480 BCE and found in the Perserschutt. It is named after the dedication on the base of the sculpture, “Euthydikos son of Thaliarchos dedicated [me]”. It now stands in the Acropolis Museum.

Archaic Greek Sculpture represents the first stages of the formation of a sculptural tradition that became one of the most significant in the entire history of Western Art. The Archaic period of Ancient Greece is poorly delimited, and there is great controversy among scholars on the subject. It is generally considered to begin between 700 and 650 BC and end between 500 and 480 BC, but some indicate a much earlier date for its beginning, 776 BC, the date of the first Olympiad. In this period the foundations were laid for the emergence of large-scale autonomous sculpture and monumental sculpture for the decoration of buildings. This evolution depended in its origins on the oriental and Egyptian influence, but soon acquired a peculiar and original character.

The Mantiklos"Apollo" is an ancient Greek sculpture from the early Archaic period. The sculpture dates to about 700-675 B.C from Thebes and measures 20.3 cm tall. It is on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.