Mycenae is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about 120 kilometres south-west of Athens; 11 kilometres north of Argos; and 48 kilometres south of Corinth. The site is 19 kilometres inland from the Saronic Gulf and built upon a hill rising 900 feet above sea level.

Mycenaean Greece was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland Greece with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art, and writing system. The Mycenaeans were mainland Greek peoples who were likely stimulated by their contact with insular Minoan Crete and other Mediterranean cultures to develop a more sophisticated sociopolitical culture of their own. The most prominent site was Mycenae, after which the culture of this era is named. Other centers of power that emerged included Pylos, Tiryns, and Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, and Athens in Central Greece, and Iolcos in Thessaly. Mycenaean settlements also appeared in Epirus, Macedonia, on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, and on Cyprus, while Mycenaean-influenced settlements appeared in the Levant and Italy.

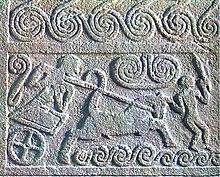

A stele, or occasionally stela when derived from Latin, is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected in the ancient world as a monument. The surface of the stele often has text, ornamentation, or both. These may be inscribed, carved in relief, or painted.

The Nordic Bronze Age is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from c. 2000/1750–500 BC.

A shaft tomb or shaft grave is a type of deep rectangular burial structure, similar in shape to the much shallower cist grave, containing a floor of pebbles, walls of rubble masonry, and a roof constructed of wooden planks.

The Treasury of Atreus or Tomb of Agamemnon is a large tholos or beehive tomb constructed between 1300 and 1250 BCE in Mycenae, Greece.

Aegean art is art that was created in the lands surrounding, and the islands within, the Aegean Sea during the Bronze Age, that is, until the 11th century BC, before Ancient Greek art. Because is it mostly found in the territory of modern Greece, it is sometimes called Greek Bronze Age art, though it includes not just the art of the Mycenaean Greeks, but also that of the non-Greek Cycladic and Minoan cultures, which converged over time.

Lion Gate is the popular modern name for the main entrance of the Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae in southern Greece. It was erected during the thirteenth century BC, around 1250 BC, in the northwestern side of the acropolis. In modern times, it was named after the relief sculpture of two lionesses in a heraldic pose that stands above the entrance.

Delphi Archaeological museum is one of the principal museums of Greece and one of the most visited. It is operated by the Greek Ministry of Culture. Founded in 1903, it has been rearranged several times and houses the discoveries made at the Panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi, which date from the Late Helladic (Mycenean) period to the early Byzantine era.

Bush Barrow is a site of the early British Bronze Age Wessex culture, at the western end of the Normanton Down Barrows cemetery in Wiltshire, England. It is among the most important sites of the Stonehenge complex, having produced some of the most spectacular grave goods in Britain. It was excavated in 1808 by William Cunnington for Sir Richard Colt Hoare. The finds, including worked gold objects, are displayed at Wiltshire Museum in Devizes.

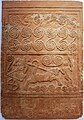

The Monteleone chariot is an Etruscan chariot dated to c. 530 BC, considered one of the world's great archaeological finds. It was originally uncovered at Monteleone di Spoleto, Umbria, Italy, and is currently a major attraction in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Grave Circle A is a 16th-century BC royal cemetery situated to the south of the Lion Gate, the main entrance of the Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae in southern Greece. This burial complex was initially constructed outside the walls of Mycenae and ultimately enclosed in the acropolis when the fortification was extended during the 13th century BC. Grave Circle A and Grave Circle B, the latter found outside the walls of Mycenae, represents one of the significant characteristics of the early phase of the Mycenaean civilization.

Ancient Greek funerary practices are attested widely in literature, the archaeological record, and in ancient Greek art. Finds associated with burials are an important source for ancient Greek culture, though Greek funerals are not as well documented as those of the ancient Romans.

Grave Circle B in Mycenae is a 17th–16th century BCE royal cemetery situated outside the late Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae, southern Greece. This burial complex was constructed outside the fortification walls of Mycenae and together with Grave Circle A represent one of the major characteristics of the early phase of the Mycenaean civilization.

The Archaeological Museum of Chora is a museum in Chora, Messenia, in southern Greece, whose collections focus on the Mycenaean civilization, particularly from the excavations at the Palace of Nestor and other regions of Messenia. The museum was founded in 1969 by the Greek Archaeological Service under the auspices of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Olympia. At the time, the latter included in its jurisdiction the larger part of Messenia.

The military nature of Mycenaean Greece in the Late Bronze Age is evident by the numerous weapons unearthed, warrior and combat representations in contemporary art, as well as by the preserved Greek Linear B records. The Mycenaeans invested in the development of military infrastructure with military production and logistics being supervised directly from the palatial centres. This militaristic ethos inspired later Ancient Greek tradition, and especially Homer's epics, which are focused on the heroic nature of the Mycenaean-era warrior élite.

The Tomb of Clytemnestra was a Mycenaean tholos type tomb built in c. 1250 BC. A number of architectural features such as the semi-column were largely adopted by later classical monuments of the first millennium BC, both in the Greek and Latin world. The Tomb of Clytemnestra with its imposing façade is together with the Treasury of Atreus the most monumental tomb of that type.

The theme of death within ancient Greek art has continued from the Early Bronze Age all the way through to the Hellenistic period. The Greeks used architecture, pottery, and funerary objects as different mediums through which to portray death. These depictions include mythical deaths, deaths of historical figures, and commemorations of those who died in war. This page includes various examples of the different types of mediums in which death is presented in Greek art.

There have been many discoveries of gold grave goods at Grave Circles A and B in the Bronze Age city of Mycenae. Gold has always been used to show status amongst the deceased when used in grave goods. While there's evidence that the practice of grave goods and monumentalizing graves to show status was used throughout Ancient Greece from the Bronze Age and passed through the Classical Period, the goods themselves changed over time. However, using gold as a material was a constant status marker. At the Grave Circles in Mycenae, there were several grave goods found that were made out of gold; masks, cups, swords, jewelry, and more. Because there were so many gold grave goods found at this site there's a legend of Golden Mycenae. Each family group would add ostentatious grave goods to compete with the other family groups for who is the wealthiest. There was more gold found at Grave Circle A and B than in all of Crete before the late Bronze Age.

The death masks of Mycenae are a series of golden funerary masks found on buried bodies within a burial site titled Grave Circle A, located within the ancient Greek city of Mycenae. There are seven discovered masks in total, found with the burials of six adult males and one male child. There were no women who had masks. They were discovered by Heinrich Schliemann during his 1876 excavation of Mycenae.