Chad is one of the 47 landlocked countries in the world and is located in North Central Africa, measuring 1,284,000 square kilometers (495,755 sq mi), nearly twice the size of France and slightly more than three times the size of California. Most of its ethnically and linguistically diverse population lives in the south, with densities ranging from 54 persons per square kilometer in the Logone River basin to 0.1 persons in the northern B.E.T. (Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti) desert region, which itself is larger than France. The capital city of N'Djaména, situated at the confluence of the Chari and Logone Rivers, is cosmopolitan in nature, with a current population in excess of 700,000 people.

Desertification is a type of gradual land degradation of fertile land into arid desert due to a combination of natural processes and human activities.

Niger is a landlocked nation in West Africa located along the border between the Sahara and Sub-Saharan regions. Its geographic coordinates are longitude 16°N and latitude 8°E

Nigeria is a country in West Africa. It shares land borders with the Republic of Benin to the west, Chad and Cameroon to the east, and Niger to the north. Its coast lies on the Gulf of Guinea in the south and it borders Lake Chad to the northeast. Notable geographical features in Nigeria include the Adamawa Plateau, Mambilla Plateau, Jos Plateau, Obudu Plateau, the Niger River, Benue River, and Niger Delta.

Mauritania, a country in the Western Region of the continent of Africa, is generally flat, its 1,030,700 square kilometres forming vast, arid plains broken by occasional ridges and clifflike outcroppings. Mauritania is the world’s largest country lying entirely below an altitude of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft). It borders the North Atlantic Ocean, between Senegal and Western Sahara, Mali and Algeria. It is considered part of both the Sahel and the Maghreb. A series of scarps face southwest, longitudinally bisecting these plains in the center of the country. The scarps also separate a series of sandstone plateaus, the highest of which is the Adrar Plateau, reaching an elevation of 500 metres or 1,640 feet. Spring-fed oases lie at the foot of some of the scarps. Isolated peaks, often rich in minerals, rise above the plateaus; the smaller peaks are called Guelbs and the larger ones Kedias. The concentric Guelb er Richat is a prominent feature of the north-central region. Kediet ej Jill, near the city of Zouîrât, has an elevation of 915 metres or 3,002 feet and is the highest peak.

Mali is a landlocked nation in West Africa, located southwest of Algeria, extending south-west from the southern Sahara Desert through the Sahel to the Sudanian savanna zone. Mali's size is 1,240,192 square kilometers.

The Sahel region, or Sahelian acacia savanna, is a biogeographical region in Africa. It is the transition zone between the more humid Sudanian savannas to its south and the drier Sahara to the north. The Sahel has a hot semi-arid climate and stretches across the southernmost latitudes of North Africa between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea. Although geographically located in the tropics, the Sahel does not have a tropical climate.

The Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel is an international organization consisting of countries in the Sahel region of Africa.

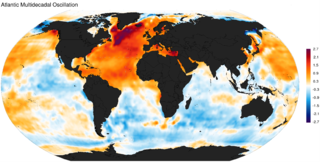

The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), also known as Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV), is the theorized variability of the sea surface temperature (SST) of the North Atlantic Ocean on the timescale of several decades.

A large-scale, drought-induced famine occurred in Africa's Sahel region and many parts of the neighbouring Sénégal River Area from February to August 2010. It is one of many famines to have hit the region in recent times.

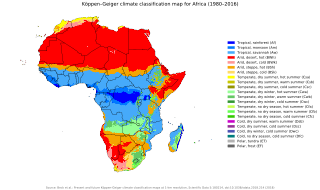

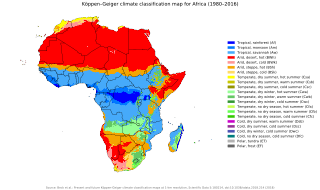

The climate of Africa is a range of climates such as the equatorial climate, the tropical wet and dry climate, the tropical monsoon climate, the semi-arid climate, the desert climate, the humid subtropical climate, and the subtropical highland climate. Temperate climates are rare across the continent except at very high elevations and along the fringes. In fact, the climate of Africa is more variable by rainfall amount than by temperatures, which are consistently high. African deserts are the sunniest and the driest parts of the continent, owing to the prevailing presence of the subtropical ridge with subsiding, hot, dry air masses. Africa holds many heat-related records: the continent has the hottest extended region year-round, the areas with the hottest summer climate, the highest sunshine duration, and more.

Climate change in Africa is an increasingly serious threat as Africa is among the most vulnerable continents to the effects of climate change. Some sources even classify Africa as "the most vulnerable continent on Earth". Climate change and climate variability will likely reduce agricultural production, food security and water security. As a result, there will be negative consequences on people's lives and sustainable development in Africa.

2012 had a very severe drought in the Sahel, the semiarid region of Africa that lies between the Sahara and the savannas. Countries included in this region are Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea. Droughts in the Sahel occur quite often and tend to reduce the already meager water supply and stress the economies of developing countries in that region.

The prehistory of West Africa timespan from the earliest human presence in the region to the emergence of the Iron Age in West Africa. West African populations were considerably mobile and interacted with one another throughout the population history of West Africa. Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP. During the Pleistocene, Middle Stone Age peoples, who dwelled throughout West Africa between MIS 4 and MIS 2, were gradually replaced by incoming Late Stone Age peoples, who migrated into West Africa as an increase in humid conditions resulted in the subsequent expansion of the West African forest. West African hunter-gatherers occupied western Central Africa earlier than 32,000 BP, dwelled throughout coastal West Africa by 12,000 BP, and migrated northward between 12,000 BP and 8000 BP as far as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania.

The effects of climate change on the water cycle are profound and have been described as an intensification or a strengthening of the water cycle. This effect has been observed since at least 1980. One example is when heavy rain events become even stronger. The effects of climate change on the water cycle have important negative effects on the availability of freshwater resources, as well as other water reservoirs such as oceans, ice sheets, the atmosphere and soil moisture. The water cycle is essential to life on Earth and plays a large role in the global climate system and ocean circulation. The warming of our planet is expected to be accompanied by changes in the water cycle for various reasons. For example, a warmer atmosphere can contain more water vapor which has effects on evaporation and rainfall.

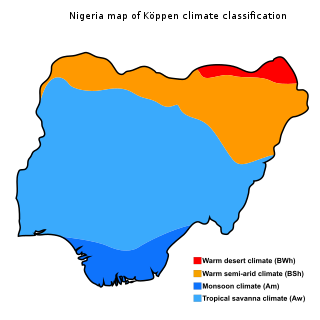

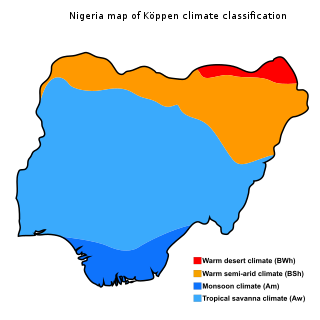

Natural disasters in Nigeria are mainly related to the climate of Nigeria, which has been reported to cause loss of lives and properties. A natural disaster might be caused by flooding, landslides, and insect infestation, among others. To be classified as a disaster, there is needs to be a profound environmental effect or human loss which must lead to financial loss. This occurrence has become an issue of concern, threatening large populations living in diverse environments in recent years.

Climate change in Ethiopia is affecting the people in Ethiopia due to increased floods, heat waves and infectious diseases. In the Awash basin in central Ethiopia floods and droughts are common. Agriculture in the basin is mainly rainfed. This applies to around 98% of total cropland as of 2012. So changes in rainfall patterns due to climate change will reduce economic activities in the basin. Rainfall shocks have a direct impact on agriculture. A rainfall decrease in the Awash basin could lead to a 5% decline in the basin's overall GDP. The agricultural GDP could even drop by as much as 10%.

The climate of Nigeria is mostly tropical. Nigeria has three distinct climatic zones, two seasons, and an average temperature ranging between 21 °C and 35 °C. Two major elements determine the temperature in Nigeria: the altitude of the sun and the atmosphere's transparency. Its rainfall is mediated by three distinct conditions including convectional, frontal, and orographical determinants. Statistics from the World Bank Group showed Nigeria's annual temperature and rainfall variations, the nation's highest average annual mean temperature was 28.1 °C in 1938, while its wettest year was 1957 with an annual mean rainfall of 1,441.45mm.

Climate change in Africa is reducing its food security. Climate change at the global, continental, and sub-continental levels has been observed to include an increase in air and ocean temperatures, sea-level rise, a decrease in snow and ice extent, an increase and decrease in precipitation, changes in terrestrial and marine biological systems, and ocean acidification. The agricultural industry is responsible for more than 60% of full time employment in Africa. Millions of people in Africa depend on the agricultural industry for their economic well-being and means of subsistence. A variety of climate change-related factors such as worsening pests and diseases that damage agriculture and livestock, altered rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, droughts, and floods are having a negative impact on the agricultural industry in Africa. Many African populations access to food is being impacted by these climate change effects on the agricultural industry, which result in a trend of decreasing crop yields, animal losses, and rising food prices.

Desertification in Africa is a form of land degradation that involves the conversion of productive land into desert or arid areas. This issue is a pressing environmental concern that poses a significant threat to the livelihoods of millions of people in Africa who depend on the land for subsistence. Geographical and environmental studies have recently coined the term desertification. Desertification is the process by which a piece of land becomes a desert, as the word desert implies. The loss or destruction of the biological potential of the land is referred to as desertification. It reduces or eliminates the potential for plant and animal production on the land and is a component of the widespread ecosystem degradation. Additionally, the term desertification is specifically used to describe the deterioration of the world's drylands, or its arid, semi-arid, and sub-humid climates. These regions may be far from the so-called natural or climatic deserts, but they still experience irregular water stress due to their low and variable rainfall. They are especially susceptible to damage from excessive human land use pressure. The causes of desertification are a combination of natural and human factors, with climate change exacerbating the problem. Despite this, there is a common misconception that desertification in Africa is solely the result of natural causes like climate change and soil erosion. In reality, human activities like deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices contribute significantly to the issue. Another misconception is that, desertification is irreversible, and that degraded land will forever remain barren wastelands. However, it is possible to restore degraded land through sustainable land management practices like reforestation and soil conservation. A 10.3 million km2 area, or 34.2% of the continent's surface, is at risk of desertification. If the deserts are taken into account, the affected and potentially affected area is roughly 16.5 million km2 or 54.6% of all of Africa. 5.7 percent of the continent's surface is made up of very severe regions, 16.2 percent by severe regions, and 12.3 percent by moderate to mild regions.