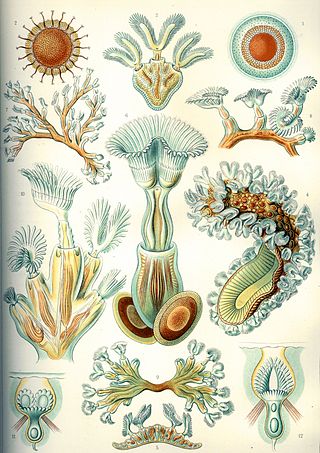

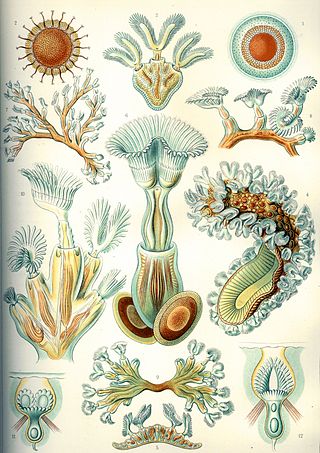

Bryozoa are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about 0.5 millimetres long, they have a special feeding structure called a lophophore, a "crown" of tentacles used for filter feeding. Most marine bryozoans live in tropical waters, but a few are found in oceanic trenches and polar waters. The bryozoans are classified as the marine bryozoans (Stenolaemata), freshwater bryozoans (Phylactolaemata), and mostly-marine bryozoans (Gymnolaemata), a few members of which prefer brackish water. 5,869 living species are known. At least, two genera are solitary ; all the rest are colonial.

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.

Graptolites are a group of colonial animals, members of the subclass Graptolithina within the class Pterobranchia. These filter-feeding organisms are known chiefly from fossils found from the Middle Cambrian through the Lower Carboniferous (Mississippian). A possible early graptolite, Chaunograptus, is known from the Middle Cambrian. Recent analyses have favored the idea that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura represents an extant graptolite which diverged from the rest of the group in the Cambrian. Fossil graptolites and Rhabdopleura share a colony structure of interconnected zooids housed in organic tubes (theca) which have a basic structure of stacked half-rings (fuselli). Most extinct graptolites belong to two major orders: the bush-like sessile Dendroidea and the planktonic, free-floating Graptoloidea. These orders most likely evolved from encrusting pterobranchs similar to Rhabdopleura. Due to their widespread abundance, plantkonic lifestyle, and well-traced evolutionary trends, graptoloids in particular are useful index fossils for the Ordovician and Silurian periods.

In biology, a colony is composed of two or more conspecific individuals living in close association with, or connected to, one another. This association is usually for mutual benefit such as stronger defense or the ability to attack bigger prey.

Stenolaemata are a class of exclusively marine bryozoans. Stenolaemates originated and diversified in the Ordovician, and more than 600 species are still alive today. All extant (living) species are in the order Cyclostomatida, the third-largest order of living bryozoans.

A clonal colony or genet is a group of genetically identical individuals, such as plants, fungi, or bacteria, that have grown in a given location, all originating vegetatively, not sexually, from a single ancestor. In plants, an individual in such a population is referred to as a ramet. In fungi, "individuals" typically refers to the visible fruiting bodies or mushrooms that develop from a common mycelium which, although spread over a large area, is otherwise hidden in the soil. Clonal colonies are common in many plant species. Although many plants reproduce sexually through the production of seed, reproduction occurs by underground stolons or rhizomes in some plants. Above ground, these plants most often appear to be distinct individuals, but underground they remain interconnected and are all clones of the same plant. However, it is not always easy to recognize a clonal colony especially if it spreads underground and is also sexually reproducing.

Tabulata, commonly known as tabulate corals, are an order of extinct forms of coral. They are almost always colonial, forming colonies of individual hexagonal cells known as corallites defined by a skeleton of calcite, similar in appearance to a honeycomb. Adjacent cells are joined by small pores. Their distinguishing feature is their well-developed horizontal internal partitions (tabulae) within each cell, but reduced or absent vertical internal partitions. They are usually smaller than rugose corals, but vary considerably in shape, from flat to conical to spherical.

Cyclostomatida, or cyclostomata, are an ancient order of stenolaemate bryozoans which first appeared in the Lower Ordovician. It consists of 7+ suborders, 59+ families, 373+ genera, and 666+ species. The cyclostome bryozoans were dominant in the Mesozoic; since that era, they have decreased. Currently, cyclostomes seldom constitute more than 20% of the species recorded in regional bryozoan faunas.

Octocorallia is a subclass of Anthozoa comprising around 3,000 species of water-based organisms formed of colonial polyps with 8-fold symmetry. It includes the blue coral, soft corals, sea pens, and gorgonians within three orders: Alcyonacea, Helioporacea, and Pennatulacea. These organisms have an internal skeleton secreted by mesoglea and polyps with eight tentacles and eight mesentaries. As with all Cnidarians these organisms have a complex life cycle including a motile phase when they are considered plankton and later characteristic sessile phase.

Constellaria is an extinct genus of bryozoan from the Middle Ordovician to Early Silurian from North America, Asia and Europe. These branching coral-like bryozoans formed bushy colonies 10-15 mm across on the seabed. The fairly thick branches were erect, often compressed in one direction, and covered with distinctive tiny, star-shaped mounds called maculae or monticules. Feeding zoids were located along the rays of the stars. The maculae probably formed "chimneys" for the expulsion of exhalant feeding currents from the surface of a colony, after water had been filtered to obtain food for the organisms.

Fenestellidae is a family of bryozoans belonging to the order Fenestrida. The skeleton of its colonies consists of stiff branches that are interconnected by narrower crossbars. The individuals of the colony inhabit one side of the branches in two parallel rows or two at the branch base and three or more rows further up. Zooids can be recognized as small rimmed pores, and in well-preserved specimens the apertures are closed by centrally perforated lids. The front of the branches carries small nodes in a row or zigzag line between the apertures. Branches split from time to time giving the colonies a fan-shape or, in the genus Archimedes, create an mesh in the shape of an Archimedes screw.

Fenestella is a genus of bryozoans or moss animals, forming fan–shaped colonies with a netted appearance. It is known from the Middle Ordovician to the early Upper Triassic (Carnian), reaching its largest diversity during the Carboniferous. Many hundreds of species have been described from marine sediments all over the world.

Dekayia is an extinct genus of Ordovician bryozoans of the family Heterotrypidae. Its colonies can be branching, encrusting, or massive. All species have acanthopores in varying sizes and numbers. The autozooecia appear angular or sub-angular viewed through a cross-section of the colony, and their walls are distinctively undulating or crenulated. Maculae generally protrude from the colony surface very little or at all, and can contain unusually large autozooecia and a cluster of mesozooecia in their centers.

Homotrypa is an extinct genus of bryozoans from the Ordovician and Silurian periods, known from fossils found in the United States. Its colonies are branch-like and have small monticules made of groups of three or four larger zooecia slightly protruding out from the main surface of the colony. In cross section, the zooecia are erect in axis and gently curve toward the surface of the colony.

Mesotrypa is a genus of bryozoans known from the Ordovician period, first described in 1893. Its colonies consist of low masses, wider than they are thick, made of superimposed layers, with small monticules on the surface of the colony.

Eridotrypa is an extinct genus of bryozoans of the family Aisenvergiidae, consistently forming colonies made of thin branches. Diaphragms are very common in colonies. Distinctively, in the exozone there are serrated dark borders separating the autozooecia.

Cyphotrypa is an extinct genus of Ordovician bryozoan. Its colonies form hemispherical shapes, with flat undersides and rounded tops. In cross-section, the zooecia fan out from the initial growth area and intersect the rounded top surface of the colony at right angles. A few scattered maculae are present, composed of a few zooecia larger than the others with mesopore-like apertures.

Monticuliporidae is a family of bryozoans belonging to the order Trepostomata, characterized by branching, encrusting, or massive colonies with regularly spaced bumps on their surfaces. It is one of the earliest bryozoan families to arise, known from the early Ordovician period, but disappears from the fossil record after the late Silurian period. Monticuliporidae had a widespread geographical range and many genera had cosmopolitan distribution.

Lichenalia is an extinct genus of cystoporate bryozoan of the family Rhinoporidae, known from the Upper Ordovician to the Middle Silurian. Its colonies could form hollow branched or tube-shaped colonies or have an encrusting growth habit. It possessed prominent lunaria and a vesicular skeleton. As in other members of Rhinoporidae, the vesicular skeleton contained tunnels that appeared like ridges on the surface of the colony. Their purpose is unknown, but they may have been used as brooding chambers.

Tarphophragma is an extinct genus of Middle and Upper Ordovician bryozoans of the family Halloporidae. Its colonies began from an encrusting base and grew into branching structures. Raised maculae made from mesozooecia and large autozooecia covered the colony's surface, and its autozooecia were arranged in a disorderly pattern. Its interzooidal budding pattern and integrate wall structure distinguish it from other genera.