Ifugao, officially the Province of Ifugao, is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital is Lagawe and it borders Benguet to the west, Mountain Province to the north, Isabela to the east, and Nueva Vizcaya to the south.

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their distinct material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. The Lapita people are believed to have originated from the northern Philippines, either directly, via the Mariana Islands, or both. They were notable for their distinctive geometric designs on dentate-stamped pottery, which closely resemble the pottery recovered from the Nagsabaran archaeological site in northern Luzon. The Lapita intermarried with the Papuan populations to various degrees, and are the direct ancestors of the Austronesian peoples of Polynesia, eastern Micronesia, and Island Melanesia.

A paddy field is a flooded field of arable land used for growing semiaquatic crops, most notably rice and taro. It originates from the Neolithic rice-farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin in southern China, associated with pre-Austronesian and Hmong-Mien cultures. It was spread in prehistoric times by the expansion of Austronesian peoples to Island Southeast Asia, Southeast Asia including Northeastern India, Madagascar, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. The technology was also acquired by other cultures in mainland Asia for rice farming, spreading to East Asia, Mainland Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed. This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants into crops.

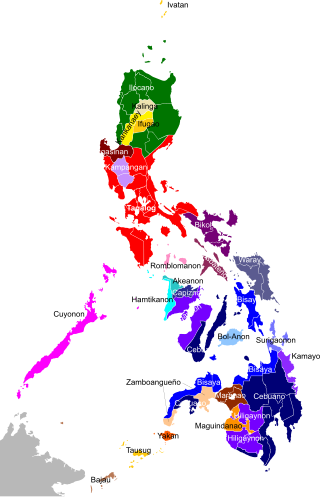

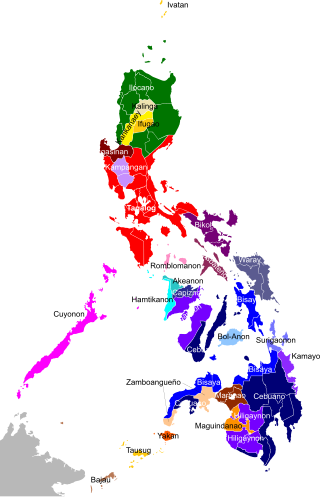

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

The Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras are a World Heritage Site consisting of a complex of rice terraces on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. They were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995, the first-ever property to be included in the cultural landscape category of the World Heritage List. This inscription has five sites: the Batad Rice Terraces and Bangaan Rice Terraces, Mayoyao Rice Terraces, Hungduan Rice Terraces and Nagacadan Rice Terraces, all in Ifugao Province. The Ifugao Rice Terraces reach a higher altitude and were built on steeper slopes than many other terraces. The Ifugao complex of stone or mud walls and the careful carving of the natural contours of hills and mountains combine to make terraced pond fields, coupled with the development of intricate irrigation systems, harvesting water from the forests of the mountain tops, and an elaborate farming system.

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austronesian languages. They also include indigenous ethnic minorities in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Hainan, the Comoros, and the Torres Strait Islands. The nations and territories predominantly populated by Austronesian-speaking peoples are sometimes known collectively as Austronesia.

The concept of a Malay race was originally proposed by the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), and classified as a brown race. Malay is a loose term used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to describe the Austronesian peoples.

The Ivatan people are an Austronesian ethnolinguistic group native to the Batanes and Babuyan Islands of the northernmost Philippines. They are genetically closely related to other ethnic groups in Northern Luzon, but also share close linguistic and cultural affinities to the Tao people of Orchid Island in Taiwan.

In a hypothesis developed by Wilhelm Solheim, the Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) is a trade and communication network that first appeared in the Asia-Pacific region during its Neolithic age, or beginning roughly around 5000 BC. Nusantao is an artificial term coined by Solheim, derived from the Austronesian root words nusa "island" and tao "man, people". Solheim's theory is an alternative hypothesis to the spread of the Austronesian language family in Southeast Asia. It contrasts the more widely accepted Out-of-Taiwan hypothesis (OOT) by Peter Bellwood.

The prehistory of the Philippines covers the events prior to the written history of what is now the Philippines. The current demarcation between this period and the early history of the Philippines is April 21, 900, which is the equivalent on the Proleptic Gregorian calendar for the date indicated on the Laguna Copperplate Inscription—the earliest known surviving written record to come from the Philippines. This period saw the immense change that took hold of the archipelago from Stone Age cultures in 50000 BC to the emergence of developed thalassocratic civilizations in the fourth century, continuing on with the gradual widening of trade until 900 and the first surviving written records.

Since H. Otley Beyer first proposed his wave migration theory, numerous scholars have approached the question of how, when and why humans first came to the Philippines. The current scientific consensus favors the "Out of Taiwan" model, which broadly match linguistic, genetic, archaeological, and cultural evidence.

Lingling-o or ling-ling-o, are a type of penannular or double-headed pendant or amulet that have been associated with various late Neolithic to late Iron Age Austronesian cultures. Most lingling-o were made in jade workshops in the Philippines, and to a lesser extent in the Sa Huỳnh culture of Vietnam, although the raw jade was mostly sourced from Taiwan.

Southeast Asia was first reached by anatomically modern humans possibly before 70,000 years ago. Anatomically modern humans are suggested to have reached Southeast Asia twice in the course of the Southern Dispersal migrations during and after the formation of a distinct East Asian clade from 70,000 to 50,000 years ago.

One of the major human migration events was the maritime settlement of the islands of the Indo-Pacific by the Austronesian peoples, believed to have started from at least 5,500 to 4,000 BP. These migrations were accompanied by a set of domesticated, semi-domesticated, and commensal plants and animals transported via outrigger ships and catamarans that enabled early Austronesians to thrive in the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, Near Oceania (Melanesia), Remote Oceania, Madagascar, and the Comoros Islands.

The post-1500s Philippines is defined by colonial powers occupying the land. Whether it be the Spanish, the Americans, or the Japanese, the Philippines were subjugated and shaped by the presence of a hegemonic power enacting dominance over the people, the land, and the culture itself. The respective field of the archaeology of the post-1500s Philippines is a particularly growing and revolutionary field, particularly seen in the archaeology of Stephen Acabado in Ifugao and Grace Barretto-Tesoro in Manila. There were also many important events that had happened during this period. In 1521, Portuguese explorer, Ferdinand Magellan discovered Homonhon Island and called it "Arcigelago de San Lazaro." Magellan became the first European to cross over the Pacific Ocean.

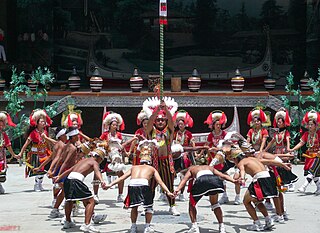

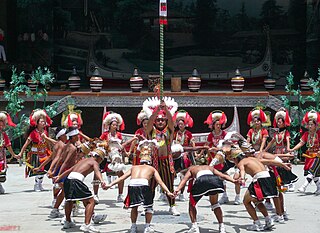

Symbolism is an abstract meaning given to an object or representative of one. Symbols can define certain aspects of cultures making them initially exclusive to particular groups. When it comes to symbolism in archaeology, artifacts found may display iconography with these abstract symbols or tell us more about the people who made them through their construction. Symbolism is not limited to only inanimate objects but can be found in the actions or being of living things as well. The Philippines, comprising more than 7,000 islands, is an archipelago where symbols of the past and present contribute to its unique culture. These symbols are influenced by and noticeable in burial practices, rituals, social status, architecture, agriculture, and The Philippines' place in the Austronesian world.

The history of rice cultivation is an interdisciplinary subject that studies archaeological and documentary evidence to explain how rice was first domesticated and cultivated by humans, the spread of cultivation to different regions of the planet, and the technological changes that have impacted cultivation over time.

The farming/language dispersal hypothesis proposes that many of the largest language families in the world dispersed along with the expansion of agriculture. This hypothesis was proposed by archaeologists Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew. It has been widely debated and archaeologists, linguists, and geneticists often disagree with all or only parts of the hypothesis.

Old Kiyyangan Village (OKV) is an archeological site in the Lazo highlands in the province of Ifugao in the Cordillera Administrative Region of the Philippines. The importance of this site is the presence of the Ifugao people and culture as the first inhabitants in the valley, who also represent one of the major indigenous Filipino societies for rice cultivation. This site is surrounded by rice terraces used for agricultural practices and remain heavily debated as to when and how recent these terraces formed. Artifacts found at this site suggest a strong influence of Christianity, mortuary rituals, and a system that defined social status according to the accumulation of various beads and ceramics.