The English Civil War was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Royalists and Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, the struggle consisted of the First English Civil War and the Second English Civil War. The Anglo-Scottish War of 1650 to 1652 is sometimes referred to as the Third English Civil War.

The 17th century lasted from January 1, 1601, to December 31, 1700 (MDCC).

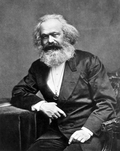

Friedrich Engels was a German philosopher, political theorist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He was also a businessman and Karl Marx's lifelong friend and closest collaborator, serving as a leading authority on Marxism.

Samuel Rawson Gardiner was an English historian who specialized in 17th-century English history as a prominent foundational historian of the Puritan revolution and the English Civil War.

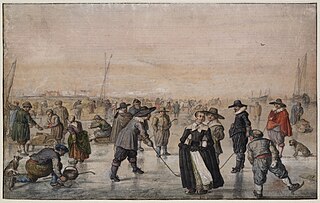

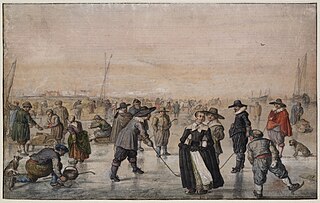

The term Cavalier was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of Charles I of England and his son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration. It was later adopted by the Royalists themselves. Although it referred originally to political and social attitudes and behaviour, of which clothing was a very small part, it has subsequently become strongly identified with the fashionable clothing of the court at the time. Prince Rupert, commander of much of Charles I's cavalry, is often considered to be an archetypal Cavalier.

William Lenthall (1591–1662) was an English politician of the Civil War period. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons for a period of almost twenty years, both before and after the execution of King Charles I.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bishops' Wars, the First and Second English Civil Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish War of 1650–1652. They resulted in the execution of Charles I, the abolition of monarchy, and founding of the Commonwealth of England, a unitary state which controlled the British Isles until the Stuart Restoration in 1660.

Early modern Britain is the history of the island of Great Britain roughly corresponding to the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Major historical events in early modern British history include numerous wars, especially with France, along with the English Renaissance, the English Reformation and Scottish Reformation, the English Civil War, the Restoration of Charles II, the Glorious Revolution, the Treaty of Union, the Scottish Enlightenment and the formation and the collapse of the First British Empire.

The Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652), also known as the Third Civil War, was the final conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between shifting alliances of religious and political factions in England, Scotland and Ireland.

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. An estimated 15% to 20% of adult males in England and Wales served in the military at some point between 1639 and 1653, while around 4% of the total population died from war-related causes. These figures illustrate the widespread impact of the conflict on society, and the bitterness it engendered as a result.

The Ordinance for the Regulating of Printing, also known as the Licensing Order of 1643, instituted pre-publication censorship upon Parliamentary England. Milton's Areopagitica was written specifically against this ordinance.

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660, which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various forms of republican government.

The Clergy Act 1640, also known as the Bishops Exclusion Act, or the Clerical Disabilities Act, was an Act of Parliament, effective 13 February 1642 that prevented men in holy orders from exercising any temporal jurisdiction or authority.

The military history of England and Wales deals with the period prior to the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707.(for the period after 1707, see Military history of the United Kingdom)

Gerald Edward Aylmer, was an English historian of 17th century England.

Lieutenant-Colonel George Joyce was an officer and Agitator in the Parliamentary New Model Army during the English Civil War.

The Stuart period of British history lasted from 1603 to 1714 during the dynasty of the House of Stuart. The period was plagued by internal and religious strife, and a large-scale civil war which resulted in the execution of King Charles I in 1649. The Interregnum, largely under the control of Oliver Cromwell, is included here for continuity, even though the Stuarts were in exile. The Cromwell regime collapsed and Charles II had very wide support for his taking of the throne in 1660. His brother James II was overthrown in 1689 in the Glorious Revolution. He was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary II and her Dutch husband William III. Mary's sister Anne was the last of the line. For the next half century James II and his son James Francis Edward Stuart and grandson Charles Edward Stuart claimed that they were the true Stuart kings, but they were in exile and their attempts to return with German aid were defeated. The period ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of King George I from the German House of Hanover.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in Die Revolution, a German monthly magazine published in New York City by Marxist Joseph Weydemeyer. Later English editions, such as the 1869 Hamburg edition with a preface by Marx, were entitled The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The essay serves as a major historiographic application of Marx's theory of historical materialism.

Bourgeois revolution is a term used in Marxist theory to refer to a social revolution that aims to destroy a feudal system or its vestiges, establish the rule of the bourgeoisie, and create a capitalist state. In colonised or subjugated countries, bourgeois revolutions often take the form of a war of national independence. The Dutch, English, American, and French revolutions are considered the archetypal bourgeois revolutions, in that they attempted to clear away the remnants of the medieval feudal system, so as to pave the way for the rise of capitalism. The term is usually used in contrast to "proletarian revolution", and is also sometimes called a "bourgeois-democratic revolution".

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the wars of the Three Kingdoms: