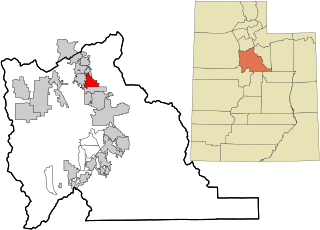

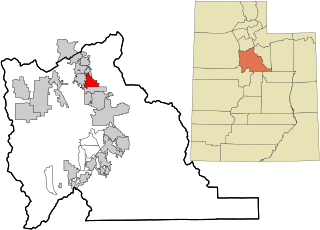

Provo is a city in and the county seat of Utah County, Utah, United States. It is 43 miles (69 km) south of Salt Lake City along the Wasatch Front, and lies between the cities of Orem to the north and Springville to the south. With a population at the 2020 census of 115,162, Provo is the fourth-largest city in Utah and the principal city in the Provo-Orem metropolitan area, which had a population of 526,810 at the 2010 census. It is Utah's second-largest metropolitan area after Salt Lake City.

Manti is a city in and the county seat of Sanpete County, Utah, United States. The population was 3,429 at the 2020 United States Census.

Payson is a city in Utah County, Utah, United States. It is part of the Provo–Orem Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 21,101 at the 2020 census.

Pleasant Grove, originally named Battle Creek, is a city in Utah County, Utah, United States, known as "Utah's City of Trees". It is part of the Provo–Orem Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 37,726 at the 2020 Census.

The Mormon Battalion was the only religious unit in United States military history in federal service, recruited solely from one religious body and having a religious title as the unit designation. The volunteers served from July 1846 to July 1847 during the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848. The battalion was a volunteer unit of between 534 and 559 Latter-day Saint men, led by Mormon company officers commanded by regular United States Army officers. During its service, the battalion made a grueling march of nearly 1,950 miles from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Diego, California.

The Mormon Trail is the 1,300-mile (2,100 km) route from Illinois to Utah on which Mormon pioneers traveled from 1846 to 1869. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail.

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also known as Latter-day Saints, who migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the Midwest to the Salt Lake Valley in what is today the U.S. state of Utah. At the time of the planning of the exodus in 1846, the territory comprising present-day Utah was part of the Republic of Mexico, with which the U.S. soon went to war over a border dispute left unresolved after the annexation of Texas. The Salt Lake Valley became American territory as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war.

Maeser Elementary was an elementary school in Provo, Utah. It was named after Karl G. Maeser. Built in 1898, it is the oldest school building in Provo, Utah. The school was designed by architect Richard C. Watkins, who also designed the Provo Third Ward Chapel and Amusement Hall, The Knight Block Building, and the Thomas N. Taylor Mansion.

Antonga, or Black Hawk, was a nineteenth-century war chief of the Timpanogos tribe in what is the present-day state of Utah. He led the Timpanogos against Mormon settlers and gained alliances with Paiute and Navajo bands in the territory against them during what became known as the Black Hawk War in Utah (1865–1872). Although Black Hawk made peace in 1867, other bands continued raiding until the US intervened with about 200 troops in 1872. Black Hawk died in 1870 from a gunshot wound he received while trying to rescue a fallen warrior, White Horse, at Gravely Ford Richfield, Utah, June 10, 1866. The wound never healed and complications set in.

Chief Walkara was a Northern Ute leader of the Utah Indians known as the Timpanogo and Sanpete Band. He had a reputation as a diplomat, horseman and warrior, and a military leader of raiding parties in Wakara's War.

Daniel Webster Jones was an American and Mormon pioneer. He was the leader of the group that colonized what eventually became Mesa, Arizona, made the first translation of selections of The Book of Mormon into Spanish, led the first Mormon missionary expedition into Mexico, dealt frequently with the American Indians, and was the leader of the group that wintered at Devil's Gate during the rescue of the stranded handcart companies in 1856.

The History of Utah is an examination of the human history and social activity within the state of Utah located in the western United States.

Ensign Peak is a dome-shaped peak in the hills just north of downtown Salt Lake City, Utah. The peak and surrounding area are part of Ensign Peak Nature Park, which is owned by the city. The hill's summit is accessed via a popular hiking trail, and provides an elevated view of Salt Lake Valley and Great Salt Lake.

The Black Hawk War, or Black Hawk's War, is the name of the estimated 150 battles, skirmishes, raids, and military engagements taking place from 1865 to 1872, primarily between Mormon settlers in Sanpete County, Sevier County and other parts of central and southern Utah, and members of 16 Ute, Southern Paiute, Apache and Navajo tribes, led by a local Ute war chief, Antonga Black Hawk. The conflict resulted in the abandonment of some settlements and hindered Mormon expansion in the region.

The Timpanogos are a tribe of Native Americans who inhabited a large part of central Utah, in particular, the area from Utah Lake east to the Uinta Mountains and south into present-day Sanpete County.

The Battle Creek massacre was a lynching of a Timpanogos group on March 5, 1849, by a group of 35 Mormon settlers at Battle Creek Canyon near present-day Pleasant Grove, Utah. It was the first violent engagement between the settlers who had begun coming to the area two years before, and was in response to reported cattle theft by the group. The attacked group was outnumbered, outgunned, and had little defense against the militia that crept in and surrounded their camp before dawn. The massacre had been ordered by Brigham Young, the Utah territory governor and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). The formation of the Mormon settlement of Utah Valley soon followed the attack at Battle Creek. One of the young survivors from the group of 17 children, women, and men who had been attacked grew up to be Antonga Black Hawk, a Timpanogos leader in the Black Hawk War (1865–1872).

Lake Point is a city on the eastern edge of northern Tooele County, Utah, United States. It is located 17 miles southwest of Salt Lake City International Airport and 11 miles north of Tooele, Utah. At its location on the south shore of the Great Salt Lake, the city is served by Interstate 80 and Utah State Route 36.

The Provo River Massacre was a violent attack and massacre in 1850 in which 90 Mormon militiamen surrounded an encampment of Timpanogos families on the Provo River, and laid siege for two days. They eventually shot between 40 and 100 Native American men and one woman with guns and a cannon during the siege, as well as during the pursuit and capture of the two groups that fled during the last night. One militiaman died and eighteen were wounded from return fire during the siege.

The Las Vegas Mission was one of the earliest European settlements in the Las Vegas Valley. It was established by missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In May 1855, at the direction of then church president Brigham Young, thirty-two missionaries were sent to evangelize among Native Americans and establish a mission outpost in the Las Vegas Valley. The mission was abandoned in December 1857 due to growing political issues revolving Mormons and the threat of Native American attacks.

Fort Supply was a Mormon pioneer-era fort in Green River County, Utah Territory, United States. Established in 1853 and abandoned during the Utah War of 1857, the fort served to solidify Mormon influence and control in the area, as a base for local missionary efforts, and to supply food and other provisions for pioneers headed to Salt Lake City. The site of the former fort is located near the modern-day community of Robertson, Uinta County, Wyoming, and a monument commemorating the settlement is maintained as a satellite site of Wyoming's Fort Bridger State Historic Site.