In physics, the Lorentz transformations are a six-parameter family of linear transformations from a coordinate frame in spacetime to another frame that moves at a constant velocity relative to the former. The respective inverse transformation is then parameterized by the negative of this velocity. The transformations are named after the Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz.

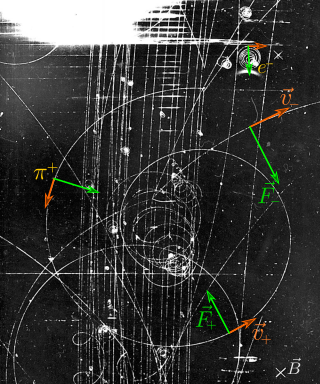

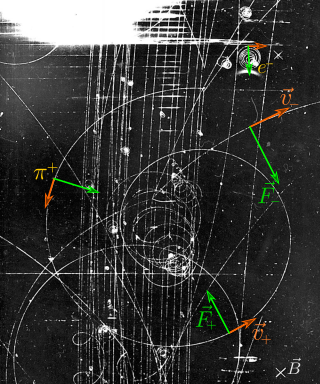

In physics, specifically in electromagnetism, the Lorentz force law is the combination of electric and magnetic force on a point charge due to electromagnetic fields. The Lorentz force, on the other hand, is a physical effect that occurs in the vicinity of electrically neutral, current-carrying conductors causing moving electrical charges to experience a magnetic force.

In statistical mechanics, the virial theorem provides a general equation that relates the average over time of the total kinetic energy of a stable system of discrete particles, bound by a conservative force with that of the total potential energy of the system. Mathematically, the theorem states where T is the total kinetic energy of the N particles, Fk represents the force on the kth particle, which is located at position rk, and angle brackets represent the average over time of the enclosed quantity. The word virial for the right-hand side of the equation derives from vis, the Latin word for "force" or "energy", and was given its technical definition by Rudolf Clausius in 1870.

In special relativity, four-momentum (also called momentum–energy or momenergy) is the generalization of the classical three-dimensional momentum to four-dimensional spacetime. Momentum is a vector in three dimensions; similarly four-momentum is a four-vector in spacetime. The contravariant four-momentum of a particle with relativistic energy E and three-momentum p = (px, py, pz) = γmv, where v is the particle's three-velocity and γ the Lorentz factor, is

In special relativity, a four-vector is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vector space considered as a representation space of the standard representation of the Lorentz group, the representation. It differs from a Euclidean vector in how its magnitude is determined. The transformations that preserve this magnitude are the Lorentz transformations, which include spatial rotations and boosts.

In the theory of relativity, four-acceleration is a four-vector that is analogous to classical acceleration. Four-acceleration has applications in areas such as the annihilation of antiprotons, resonance of strange particles and radiation of an accelerated charge.

In the special theory of relativity, four-force is a four-vector that replaces the classical force.

In mathematics, the covariant derivative is a way of specifying a derivative along tangent vectors of a manifold. Alternatively, the covariant derivative is a way of introducing and working with a connection on a manifold by means of a differential operator, to be contrasted with the approach given by a principal connection on the frame bundle – see affine connection. In the special case of a manifold isometrically embedded into a higher-dimensional Euclidean space, the covariant derivative can be viewed as the orthogonal projection of the Euclidean directional derivative onto the manifold's tangent space. In this case the Euclidean derivative is broken into two parts, the extrinsic normal component and the intrinsic covariant derivative component.

In differential geometry, the four-gradient is the four-vector analogue of the gradient from vector calculus.

In differential geometry, a tensor density or relative tensor is a generalization of the tensor field concept. A tensor density transforms as a tensor field when passing from one coordinate system to another, except that it is additionally multiplied or weighted by a power W of the Jacobian determinant of the coordinate transition function or its absolute value. A tensor density with a single index is called a vector density. A distinction is made among (authentic) tensor densities, pseudotensor densities, even tensor densities and odd tensor densities. Sometimes tensor densities with a negative weight W are called tensor capacity. A tensor density can also be regarded as a section of the tensor product of a tensor bundle with a density bundle.

When studying and formulating Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, various mathematical structures and techniques are utilized. The main tools used in this geometrical theory of gravitation are tensor fields defined on a Lorentzian manifold representing spacetime. This article is a general description of the mathematics of general relativity.

In a relativistic theory of physics, a Lorentz scalar is a scalar expression whose value is invariant under any Lorentz transformation. A Lorentz scalar may be generated from, e.g., the scalar product of vectors, or by contracting tensors. While the components of the contracted quantities may change under Lorentz transformations, the Lorentz scalars remain unchanged.

In electromagnetism, the electromagnetic tensor or electromagnetic field tensor is a mathematical object that describes the electromagnetic field in spacetime. The field tensor was first used after the four-dimensional tensor formulation of special relativity was introduced by Hermann Minkowski. The tensor allows related physical laws to be written concisely, and allows for the quantization of the electromagnetic field by the Lagrangian formulation described below.

In physics, the algebra of physical space (APS) is the use of the Clifford or geometric algebra Cl3,0(R) of the three-dimensional Euclidean space as a model for (3+1)-dimensional spacetime, representing a point in spacetime via a paravector.

A theoretical motivation for general relativity, including the motivation for the geodesic equation and the Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the dynamics of particles in circular orbits about the Earth. A key advantage in examining circular orbits is that it is possible to know the solution of the Einstein Field Equation a priori. This provides a means to inform and verify the formalism.

The derivation of the Navier–Stokes equations as well as their application and formulation for different families of fluids, is an important exercise in fluid dynamics with applications in mechanical engineering, physics, chemistry, heat transfer, and electrical engineering. A proof explaining the properties and bounds of the equations, such as Navier–Stokes existence and smoothness, is one of the important unsolved problems in mathematics.

In relativity, proper velocityw of an object relative to an observer is the ratio between observer-measured displacement vector and proper time τ elapsed on the clocks of the traveling object:

The Cauchy momentum equation is a vector partial differential equation put forth by Cauchy that describes the non-relativistic momentum transport in any continuum.

In theoretical physics, relativistic Lagrangian mechanics is Lagrangian mechanics applied in the context of special relativity and general relativity.

Accelerations in special relativity (SR) follow, as in Newtonian Mechanics, by differentiation of velocity with respect to time. Because of the Lorentz transformation and time dilation, the concepts of time and distance become more complex, which also leads to more complex definitions of "acceleration". SR as the theory of flat Minkowski spacetime remains valid in the presence of accelerations, because general relativity (GR) is only required when there is curvature of spacetime caused by the energy–momentum tensor. However, since the amount of spacetime curvature is not particularly high on Earth or its vicinity, SR remains valid for most practical purposes, such as experiments in particle accelerators.