Amblypoda was a taxonomic hypothesis uniting a group of extinct, herbivorous mammals. They were considered a suborder of the primitive ungulate mammals and have since been shown to represent a polyphyletic group.

Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

The narwhal, also known as a narwhale, is a medium-sized toothed whale that lives year-round in Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada and Russia. It is one of two living species of whale in the family Monodontidae, along with the beluga whale, and the only species in the genus Monodon. The narwhal males are distinguished by a long, straight, helical tusk, which in actuality is an oversized canine tooth. On the other hand, females rarely possess this feature; an example of sexual dimorphism. The narwhal was one of many species described by Carl Linnaeus in his publication Systema Naturae in 1758.

Paraceratherium is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch. The first fossils were discovered in what is now Pakistan, and remains have been found across Eurasia between China and the Balkans. Paraceratherium means "near the hornless beast", in reference to Aceratherium, the genus in which the type species P. bugtiense was originally placed.

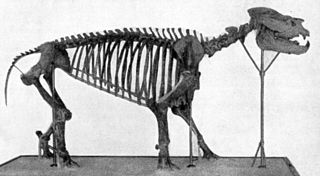

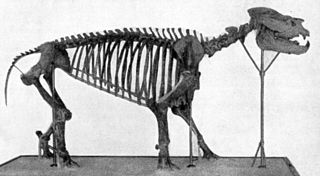

Dinocerata also known as uintatheres, is an extinct order of large herbivorous hoofed mammals with horns and protuberant canine teeth, known from the Paleocene and Eocene of Asia and North America. With body masses ranging up to 4,500 kilograms (9,900 lb) they represent some of the earliest known large mammals.

Eobasileus cornutus was a prehistoric species of dinocerate mammal.

Metamynodon is an extinct genus of amynodont rhino that lived in North America and Asia from the late Eocene until early Oligocene, although the questionable inclusion of M. mckinneyi could extend their range to the Middle Eocene. The various species were large, displaying a suit of semiaquatic adaptations more similar to those of the modern hippopotamus, despite their closer affinities with rhinoceroses.

Anthracobunidae is an extinct family of stem perissodactyls that lived in the early to middle Eocene period. They were originally considered to be a paraphyletic family of primitive proboscideans possibly ancestral to the Moeritheriidae and the desmostylians. The family has also thought to be ancestral to the Sirenia.

Hypercoryphodon is an extinct genus of rhinoceros-sized pantodont native to Late Eocene Mongolia, and was very similar to its ancestor, Coryphodon. Described from a skull, Hypercoryphodon is a quadrupedal hippopotamus-like herbivore that may have been able to adapt its feeding to suit different situations. It is thought to have possibly lived in wetland to forest ecosystems that it might have shared with other herbivores such as dinoceratans like Gobiatherium.

Prodinoceras is the earliest known uintathere genus, which lived in the late Paleocene of Mongolia. It was a relatively small uintathere, reaching 2.9 m in length. It is also regarded as the most basal uintathere, as, although it had the characteristic fang-like tusks, it had yet to evolve the characteristic knob-like horns.

Ninjemys oweni is an extinct large meiolaniid stem-turtle from Pleistocene Queensland and possibly New South Wales (Australia). It overall resembled its relative, Meiolania, save that the largest pair of horns on its head stuck out to the sides, rather than point backwards, the larger scales at the back of its skull and the tail club which is made up of only two tail rings rather than four. With a shell length of approximately 1 m it is a large turtle and among the largest meiolaniids. Ninjemys is primarily known from a well preserved skull and associated tail armor, which were initially thought to have belonged to the giant monitor lizard Megalania.

Amynodontidae is a family of extinct average-sized rhinocerotoids. They are commonly portrayed as semiaquatic hippo-like rhinos but this description only fits members of the Metamynodontini; other groups of amynodonts like the cadurcodontines had more typical ungulate proportions and convergently evolved a tapir-like proboscis.

Carodnia is an extinct genus of South American ungulate known from the Early Eocene of Brazil, Argentina, and Peru. Carodnia is placed in the order Xenungulata together with Etayoa and Notoetayoa.

Astrapotheria is an extinct order of South American and Antarctic hoofed mammals that existed from the late Paleocene to the Middle Miocene, 59 to 11.8 million years ago. Astrapotheres were large, rhinoceros-like animals and have been called one of the most bizarre orders of mammals with an enigmatic evolutionary history.

Gnathabelodon is an extinct genus of gomphothere endemic to North America that includes species that lived during the Middle to Late Miocene.

The Clarkforkian North American Stage, on the geologic timescale, is the North American faunal stage according to the North American Land Mammal Ages chronology (NALMA), typically set from 56,800,000 to 55,400,000 years BP lasting 1.4 million years.

Paleontology in Texas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Texas. Author Marian Murray has said that "Texas is as big for fossils as it is for everything else." Some of the most important fossil finds in United States history have come from Texas. Fossils can be found throughout most of the state. The fossil record of Texas spans almost the entire geologic column from Precambrian to Pleistocene. Shark teeth are probably the state's most common fossil. During the early Paleozoic era Texas was covered by a sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, graptolites, and trilobites. Little is known about the state's Devonian and early Carboniferous life. Evidence indicates that during the late Carboniferous the state was home to marine life, land plants and early reptiles. During the Permian, the seas largely shrank away, but nevertheless coral reefs formed in the state. The rest of Texas was a coastal plain inhabited by early relatives of mammals like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus. During the Triassic, a great river system formed in the state that was inhabited by crocodile-like phytosaurs. Little is known about Jurassic Texas, but there are fossil aquatic invertebrates of this age like ammonites in the state. During the Early Cretaceous local large sauropods and theropods left a great abundance of footprints. Later in the Cretaceous, the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway and home to creatures like mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and few icthyosaurs. Early Cenozoic Texas still contained areas covered in seawater where invertebrates and sharks lived. On land the state would come to be home to creatures like glyptodonts, mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, titanotheres, uintatheres, and dire wolves. Archaeological evidence suggests that local Native Americans knew about local fossils. Formally trained scientists were already investigating the state's fossils by the late 1800s. In 1938, a major dinosaur footprint find occurred near Glen Rose. Pleurocoelus was the Texas state dinosaur from 1997 to 2009, when it was replaced by Paluxysaurus jonesi after the Texan fossils once referred to the former species were reclassified to a new genus.

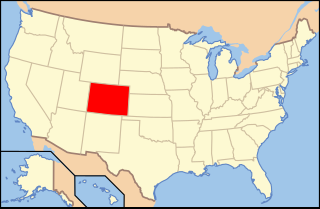

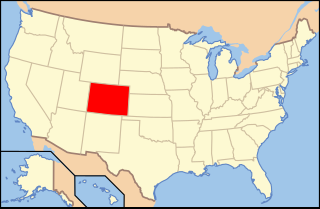

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

The Gelocidae are an extinct family of hornless ruminantia that are estimated to have lived during the Eocene and Oligocene epochs, from 36 MYA to 6 MYA. The family generally includes ruminants with dental traits of both the Tragulina and Pecora, making it a notorious wastebasket taxon with unresolved affinities.

A narluga is a hybrid born from mating a female narwhal and a male beluga whale. Narwhals and beluga whales are both cetaceans found in the High Arctic and are the only two living members of the family Monodontidae.