Extra Texture (Read All About It) is the sixth studio album by English musician George Harrison, released on 22 September 1975. It was Harrison's final album under his contract with Apple Records and EMI, and the last studio album issued by Apple. The release came nine months after his troubled 1974 North American tour with Ravi Shankar and the poorly received Dark Horse album.

The discography of English singer-songwriter and former member of the Beatles, George Harrison consists of 12 studio albums, two live albums, four compilation albums, 35 singles, two video albums and four box sets. Harrison's first solo releases – the Wonderwall Music film soundtrack (1968) and Electronic Sound (1969) – were almost entirely instrumental works, issued during the last two years of the Beatles' career. Following the band's break-up in April 1970, Harrison continued to produce recordings by his fellow Apple Records acts, notably former bandmate Ringo Starr. He recorded and collaborated with a wide range of artists, including Shankar, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton and Gary Wright.

"You" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released as the opening track of his 1975 album Extra Texture . It was also the album's lead single, becoming a top 20 hit in America and reaching number 9 in Canada. A 45-second instrumental portion of the song, titled "A Bit More of You", appears on Extra Texture also, opening side two of the original LP format. Harrison wrote "You" in 1970 as a song for Ronnie Spector, formerly of the Ronettes, and wife of Harrison's All Things Must Pass co-producer Phil Spector. The composition reflects Harrison's admiration for 1960s American soul/R&B, particularly Motown.

"Don't Let Me Wait Too Long" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, released on his 1973 album Living in the Material World. It was scheduled to be issued as a single in September that year, as the follow-up to "Give Me Love ", but the release was cancelled. Music critics have traditionally viewed "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long" as a highlight of the Material World album, praising its pop qualities and production, with some considering the song worthy of hit status.

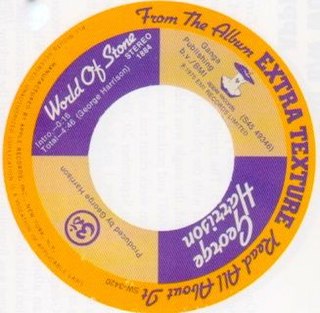

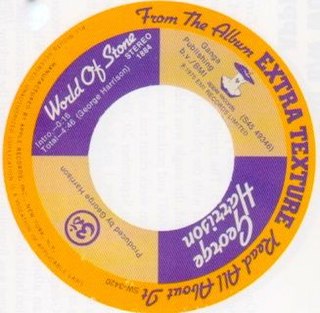

"World of Stone" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, released in 1975 on Extra Texture , his final album for Apple Records. It was also issued as the B-side of the album's lead single, "You". Harrison wrote the song in 1973 but recorded it two years later, following the unfavourable critical reception afforded his 1974 North American tour with Ravi Shankar and the Dark Horse album. Due to its context on release, commentators view "World of Stone" as a plea from Harrison for tolerance from these detractors. According to some of his biographers, the lyrics reflect Harrison's doubts regarding his devotion to a spiritual path – an apparent crisis of faith that followed his often-unwelcome spiritual pronouncements during the tour, and which permeated his work throughout 1975.

"Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison from his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. Harrison wrote the song as a tribute to Frank Crisp, a nineteenth-century lawyer and the original owner of Friar Park – the Victorian Gothic residence in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, that Harrison purchased in early 1970. Commentators have likened the song to a cinematic journey through the grand house and the grounds of the estate.

"Run of the Mill" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released on his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. Harrison wrote the song shortly after the Beatles' troubled Get Back sessions in early 1969, during a period when his growth as a songwriter had inadvertently contributed to the dysfunction within the Beatles' group dynamic. The lyrics reflect the toll that running their company Apple Corps had taken on relationships within the band, especially between Paul McCartney and the other three Beatles, as well as Harrison's dismay at John Lennon's emotional withdrawal from the band. Commentators recognise "Run of the Mill" as one of several Harrison compositions that provide an insight into events behind the Beatles' break-up, particularly the difficulties surrounding Apple.

"Awaiting on You All" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released on his 1970 triple album, All Things Must Pass. Along with the single "My Sweet Lord", it is among the more overtly religious compositions on All Things Must Pass, and the recording typifies co-producer Phil Spector's influence on the album, due to his liberal use of reverberation and other Wall of Sound production techniques. Harrison recorded the track in London backed by musicians such as Eric Clapton, Bobby Whitlock, Klaus Voormann, Jim Gordon and Jim Price – many of whom he had toured with, as Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, in December 1969, while still officially a member of the Beatles. Musically, the composition reflects Harrison's embracing of the gospel music genre, following his production of fellow Apple Records artists Billy Preston and Doris Troy.

"I Dig Love" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison from his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. A paean to free love, it marks a departure from the more profound, spiritually oriented subject matter of much of that album. Musically, the song reflects Harrison's early experimentation with slide guitar, a technique that he was introduced to while touring with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends in December 1969.

"Living in the Material World" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison that was released as the title track of his 1973 album. In the song's lyrics, Harrison contrasts the world of material concerns with his commitment to a spiritual path, and the conflict is further represented in the musical arrangement as the rock accompaniment alternates with sections of Indian sounds. Inspired by Gaudiya Vaishnava teacher A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the song promotes the need to recognise the illusory nature of human existence and escape the constant cycle of reincarnation, and thereby attain moksha in the Hindu faith. The contrasts presented in "Living in the Material World" inspired the Last Supper-style photograph by Ken Marcus that appeared inside the album's gatefold cover, and also designer Tom Wilkes's incorporation of Krishna-related symbolism elsewhere in the packaging.

"Māya Love" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released on his 1974 album Dark Horse. The song originated as a slide guitar tune, to which Harrison later added lyrics relating to the illusory nature of love – maya being a Sanskrit term for "illusion", or "that which is not". Harrison's biographers consider the lyrical theme to be reflective of his failed marriage to Pattie Boyd, who left him for his friend Eric Clapton shortly before the words were written. Harrison recorded the song at his home, Friar Park, on the eve of his North American tour with Ravi Shankar, which took place in November and December 1974. The recording features Harrison's slide guitar extensively and contributions from four musicians who formed the nucleus of his tour band: Billy Preston, Tom Scott, Willie Weeks and Andy Newmark. Reviewers note the track as an example of its parent album's more diverse musical genres, namely funk and rhythm and blues, compared with the more traditional rock orientation of Harrison's earlier solo work.

"It Is 'He' " is a song by English musician George Harrison, released as the final track of his 1974 album Dark Horse. Harrison was inspired to write the song while in the Hindu holy city of Vrindavan, in northern India, with his friend Ravi Shankar. The composition originated on a day that Harrison describes in his autobiography as "my most fantastic experience", during which his party and their ascetic guide toured the city's temples. The song's choruses were adapted from the Sanskrit chant they sang before visiting Seva Kunj, a park dedicated to Krishna's childhood. The same pilgrimage to India led to Harrison staging Shankar's Music Festival from India in September 1974 and undertaking a joint North American tour with Shankar at the end of that year.

"The Answer's at the End" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, released in 1975 on his final album for Apple Records, Extra Texture . Part of the song lyrics came from a wall inscription at Harrison's nineteenth-century home, Friar Park, a legacy of the property's original owner, Sir Frank Crisp. This aphorism, beginning "Scan not a friend with a microscopic glass", had resonated with Harrison since he bought Friar Park in 1970, and it was a quote he often used when discussing his difficult relationship with his former Beatles bandmate Paul McCartney.

"Ooh Baby (You Know That I Love You)" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released in 1975 on his album Extra Texture (Read All About It). Harrison wrote the composition as a tribute to American singer Smokey Robinson, whom he often identified as one of his favourite vocalists and songwriters. The song was intended as a companion piece to Robinson's 1965 hit with the Miracles, "Ooo Baby Baby", and its inclusion on Extra Texture contributed to that album's standing as Harrison's soul music album. His impersonation of Robinson's celebrated vocal style on the track, including portions sung in falsetto, contrasted with Harrison's hoarse, laryngitis-marred singing on his 1974 North American tour and the poorly received Dark Horse album.

"Can't Stop Thinking About You" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released in 1975 on his final album for Apple Records, Extra Texture . A love song in the style of a soul/R&B ballad, it was written by Harrison in December 1973, towards the end of his marriage to Pattie Boyd and while he was having an affair with Maureen Starkey, the wife of his former Beatles bandmate Ringo Starr. Having first considered the song for his 1974 release Dark Horse, Harrison recorded "Can't Stop Thinking About You" in Los Angeles in May 1975 for his so-called "soul album", Extra Texture. Some authors view its inclusion on the latter release as an obvious attempt by Harrison to commercialise the album, in response to the harsh critical reception afforded Dark Horse and his 1974 North American tour.

"His Name Is Legs (Ladies and Gentlemen)" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, released in 1975 as the closing track of his album Extra Texture (Read All About It). The song is a tribute to "Legs" Larry Smith, the drummer with the 1960s satirical-comedy group the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and one of many comedians with whom Harrison began associating during the 1970s. Smith appears on the recording, delivering a spoken monologue, while Harrison's lyrics similarly reflect the comedian's penchant for zany wordplay. The song serves as a precursor to Harrison's work with Monty Python members Eric Idle and Michael Palin, including his production of the troupe's 1975 single "The Lumberjack Song" and films such as Life of Brian (1979) that he produced under the aegis of his company HandMade Films.

"Beautiful Girl" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released on his 1976 album Thirty Three & 1/3. Harrison began writing the song in 1969 and considered recording it for his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. In its finished, 1976 form, the lyrics of "Beautiful Girl" were inspired by Harrison's second wife, Olivia Arias.

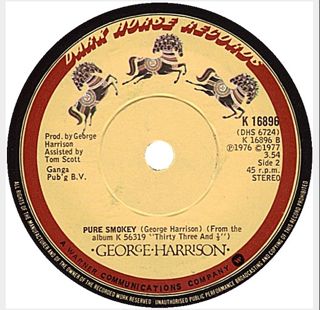

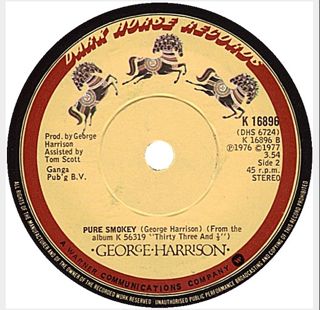

"Pure Smokey" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released in 1976 on his debut album for Dark Horse Records, Thirty Three & 1/3. The song was the second of Harrison's musical tributes to American soul singer Smokey Robinson, following "Ooh Baby " in 1975. Harrison frequently cited Robinson as one of his favourite vocalists and songwriters, and Robinson's group the Miracles had similarly influenced the Beatles during the 1960s. In the lyrics to "Pure Smokey", Harrison gives thanks for the gift of Robinson's music, while making a statement regarding the importance of expressing appreciation and gratitude, rather than forgetting to do so and later regretting it. The song title came from the name of Robinson's 1974 album Pure Smokey.

"Soft Touch" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison from his 1979 album George Harrison. It was also issued as the B-side of the album's lead single, "Blow Away", in Britain and some other countries, while in markets such as North America, it was the B-side of the second single, "Love Comes to Everyone". Harrison wrote the song while in the Virgin Islands with his future wife, Olivia Arias, shortly before recording his 1976 album Thirty Three & ⅓. The song is a love song in which Harrison also conveys his wonder at the idyllic island setting.

"Circles" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, released as the final track of his 1982 album Gone Troppo. Harrison wrote the song in India in 1968 while he and the Beatles were studying Transcendental Meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The theme of the lyrics is reincarnation. The composition reflects the cyclical aspect of human existence as, according to Hindu doctrine, the soul continues to pass from one life to the next. Although the Beatles never formally recorded it, "Circles" was among the demos the group made at Harrison's Esher home, Kinfauns, in May 1968, while considering material for their double album The Beatles.