Related Research Articles

Pope Nicholas I, called Nicholas the Great, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 858 until his death. He is remembered as a consolidator of papal authority, exerting decisive influence on the historical development of the papacy and its position among the Christian nations of Western Europe. Nicholas I asserted that the pope should have suzerainty over all Christians, even royalty, in matters of faith and morals.

Lothair II was the king of Lotharingia from 855 until his death in 869. He was the second son of Emperor Lothair I and Ermengarde of Tours. He was married to Teutberga, daughter of Boso the Elder.

Charles III, also known as Charles the Fat, was the emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 881 to 887. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, Charles was the youngest son of Louis the German and Hemma, and a great-grandson of Charlemagne. He was the last Carolingian emperor of legitimate birth and the last to rule a united kingdom of the Franks.

Lothair, sometimes called Lothair II, III or IV, was the penultimate Carolingian king of West Francia, reigning from 10 September 954 until his death in 986.

Hincmar, archbishop of Reims, was a Frankish jurist and theologian, as well as the friend, advisor and propagandist of Charles the Bald. He belonged to a noble family of northern Francia.

Rorik was a Danish Viking, who ruled over parts of Friesland between 841 and 873, conquering Dorestad and Utrecht in 850. Rorik swore allegiance to Louis the German in 873. He was born in Denmark around 800. He died at some point between 873 and 882.

Tilpin, Latin Tilpinus, also called Tulpin, a name later corrupted as Turpin, was the bishop of Reims from about 748 until his death. He was for many years regarded as the author of the legendary Historia Caroli Magni, which is thus also known as the "Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle". He appears as one of the Twelve Peers of France in a number of the chansons de geste, the most important of which is The Song of Roland. His portrayal in the chansons, often as a warrior-bishop, is completely fictitious.

Fulk the Venerable was archbishop of Reims from 883 until his death. He was a key figure in the political conflicts of the West Frankish kingdom that followed the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire in the late ninth century.

Arnulf was the illegitimate son of King Lothair of France. He became archbishop of Reims.

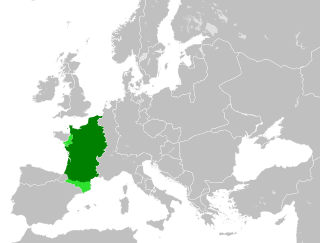

In medieval historiography, West Francia or the Kingdom of the West Franks constitutes the initial stage of the Kingdom of France and extends from the year 843, from the Treaty of Verdun, to 987, the beginning of the Capetian dynasty. It was created from the division of the Carolingian Empire following the death of Louis the Pious, with its neighbor East Francia eventually evolving into the Kingdom of Germany.

Carloman was the youngest son of Charles the Bald, king of West Francia, and his first wife, Ermentrude. He was intended for an ecclesiastical career from an early age, but in 870 rebelled against his father and tried to claim a part of the kingdom as an inheritance.

Richilde of Provence was the second wife of the Frankish emperor Charles the Bald. By her marriage, she became queen and later empress. She ruled as regent in 877.

Theotgaud was the archbishop of Trier from 850 until his deposition in 867. He was the abbot of Mettlach prior to his election in 847 to succeed his uncle, Hetto, as archbishop.

Pardulus of Laon was bishop of Laon from 847 to 857. He is known for his participation in theological controversy. A letter of his to Hincmar of Reims is known.

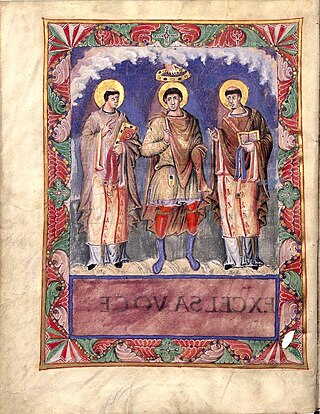

The De divortio Lotharii regis et Theutbergae reginae is an extended mid ninth-century treatise written by Hincmar, Archbishop of Reims, which survives in a single manuscript, Paris BnF. lat. 2866. The front few pages of this manuscript have been lost, and so this is an assumed title. It explores the issues arising from the attempt by Lothar II, king of Lotharingia (855–869), to rid himself of his wife Teutberga and replace her with his concubine, Waldrada. Hincmar is primarily concerned with defining what marriage is and how it may be ended, and with the duties of bishops and of kings. However, in the course of discussing these questions, he touches on many other issues too, and gives much detail on ninth-century politics and religious practice in Francia.

Wulfad was the archbishop of Bourges from 866 until his death. Prior to that, he was the abbot of Montier-en-Der and Soissons. He also served as a tutor to Carloman, a younger son of King Charles the Bald. Carloman succeeded Wulfad as abbot of Soissons in 860.

Odo I was a West Frankish prelate who served as abbot of Corbie in the 850s and as bishop of Beauvais from around 860 until his death in 881. He was a courtier and a diplomat, going on missions to East Francia and the Holy See.

Immo was the bishop of Noyon from between 835 and 841 until his death at the hands of a group of Vikings. During the civil war that convulsed the Carolingian Empire following the death of Emperor Louis the Pious in 840, Immo supported the emperor's youngest son, Charles the Bald, from 841.

Adventius was the Bishop of Metz from 855 until his death in 875. He was a prominent figure within the courts of the Carolingian kings Lothar II (855–869) and Charles the Bald (840–877).

The Council of Metz of 863 was arranged by Pope Nicholas I to discuss the divorce case of Lothar II, king of Lotharingia, and his wife Theutberga. The council was mainly attended by Lothar II's supporters, and thus concluded the divorce case in his favour; this decision was later overruled by Pope Nicholas I who suspected foul play. It was the fourth and final council called during the reign of Lothar II. No documents from the council survive, but as the council was controversial it is discussed in other medieval sources such as the letters of Pope Nicholas I, the Annals of St Bertin, the Annals of Fulda and the Liber Pontificalis.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 McKeon, Peter. R. (1978). Hincmar of Laon and Carolingian Politics. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nelson, Janet (1992). Charles the Bald. Harlow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 West, Charles (2015). "Lordship in Ninth-Century Francia: the case of Bishop Hincmar of Laon and his followers" (PDF). Past and Present (226): 3–40. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtu044.

- ↑ Charles, West (2017). "Verify the Source".

- ↑ Hincmar of Reims, trans. C. West (868). "Hincmar of Reims, Rotula" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morrison, Karl. F. (1964). The Two Kingdoms: Ecclesiology in Carolingian Political Thought. Princeton.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Nelson, Janet (1991). The Annals of St-Bertin. Manchester. pp. 150–152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)