Ellicott City is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in, and the county seat of, Howard County, Maryland, United States. Part of the Baltimore metropolitan area, its population was 65,834 at the 2010 census, qualifying it as the largest unincorporated county seat in the country.

Korean Americans are Americans of Korean heritage or descent, with a very small minority from North Korea, China, Japan, and the Post-Soviet states). The Korean American community constitutes about 0.6% of the United States population, or about 1.8 million people, and is the fifth largest Asian American subgroup, after the Chinese American, Filipino American, Indian American, and Vietnamese American communities. The U.S. is home to the largest Korean diaspora community in the world.

Koreatown is an ethnic enclave in Toronto, Canada known for its Korean businesses. It is located along Bloor Street between Christie and Bathurst Streets in Seaton Village. The area developed during the 1970s due to an influx of Korean immigrants.

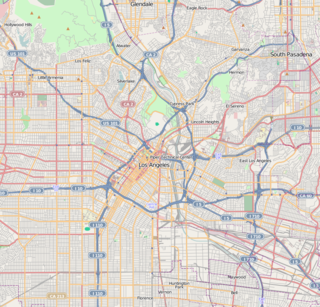

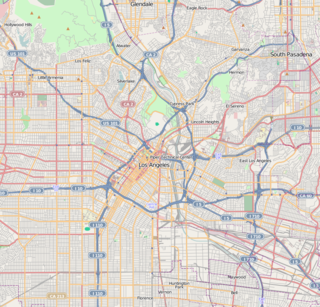

Koreatown is a neighborhood in Central Los Angeles, California, centered near Eighth Street and Irolo Street, west of MacArthur Park.

A Koreatown, also known as a Little Korea or Little Seoul, is a Korean-dominated ethnic enclave within a city or metropolitan area outside the Korean Peninsula.

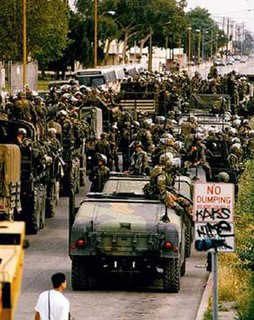

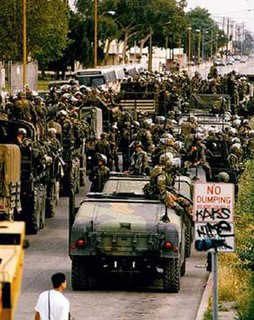

The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sometimes called the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, were a series of riots and civil disturbances that occurred in Los Angeles County in April and May 1992. Unrest began in South Central Los Angeles on April 29, after a trial jury acquitted four officers of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for usage of excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King, which had been videotaped and widely viewed in TV broadcasts.

Charles Village is a neighborhood located in the north-central area of Baltimore, Maryland, USA. It is a middle-class area with many single-family homes that is in proximity to many of Baltimore's urban amenities. The neighborhood began in 1869 when 50 acres (200,000 m2) of land were purchased for development. The land was divided and turned over to various builders who constructed home exteriors, leaving the interiors to be custom built according to buyer specifications. The area was first developed as a streetcar suburb in the early 20th century, and is thought to be the first community to employ tract housing tactics. At the time, the area was known as Peabody Heights; the moniker Charles Village, derived from Charles Street, the area's major north-south corridor, was coined in the 1970s as the beginning of a process of conceptually grouping a large and somewhat heterogeneous area. The neighborhood history has been researched and published by Gregory J. Alexander and Paul K. Williams in their book Charles Village: A Brief History.

Grand Mart International Food is a Korean supermarket chain primarily located in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, with locations in North Carolina and Georgia. It is owned by Annandale, Virginia-based Man Min Corporation, a family company. It was founded in 2002 by David Min Sik Kang, a Korean-American entrepreneur who originally owned small Korean grocery stores in Washington, D.C.

Fiesta Mart, L.L.C., formerly Fiesta Mart Inc., is a Latino-American supermarket chain based in Houston, Texas that was established in 1972. Fiesta Mart stores are located in Texas. The chain uses a cartoon parrot as a mascot. As of 2004 it operated 34 supermarkets in Greater Houston, 16 supermarkets in other locations in Texas, and 17 Beverage Mart liquor store locations. During the same year it had 7.5% of the grocery market share in Greater Houston. Many of its stores were located in Hispanic neighborhoods and other minority neighborhoods.

Korean Canadians are Canadian Citizens who are of full or partial Korean descent, It also includes Canadian-born Koreans. According to South Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, there were 240,942 ethnic Koreans or people of Korean descent in Canada as of 2017, making them the fourth-largest Korean diaspora population.

Fulton is an unincorporated community and census-designated place located in southern Howard County, Maryland, United States. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 2,049.

Interminority racism is prejudice or discrimination between racial minorities. This article strictly addresses interminority racism as it exists in the United States.

The history of the Czechs in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. Thousands of Czechs immigrated to East Baltimore during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming an important component of Baltimore's ethnic and cultural heritage. The Czech community has founded a number of cultural institutions to preserve the city's Czech heritage, including a Roman Catholic church, a heritage association, a gymnastics association, an annual festival, a language school, and a cemetery. During the height of the Czech community in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Baltimore was home to 12,000 to 15,000 people of Czech birth or heritage. The population began to decline during the mid-to-late 20th century, as the community assimilated and aged and many Czech Americans moved to the suburbs of Baltimore. By the 1980s and early 1990s, the former Czech community in East Baltimore had been almost entirely dispersed, though a few remnants of the city's Czech cultural legacy still remain.

There have been a variety of ethnic groups in Baltimore, Maryland and its surrounding area for 12,000 years. Prior to European colonization, various Native American nations have lived in the Baltimore area for nearly 12 millennia, with the earliest known Native inhabitants dating to the 10th century BCE. Following Baltimore's foundation as a subdivision of the Province of Maryland by British colonial authorities in 1661, the city became home to numerous European settlers and immigrants and their African slaves. Since the first English settlers arrived, substantial immigration from all over Europe, the presence of a deeply rooted community of free black people that was the largest in the pre-Civil War United States, out-migration of African-Americans from the Deep South, out-migration of White Southerners from Appalachia, out-migration of Native Americans from the Southeast such as the Lumbee and the Cherokee, and new waves of more recent immigrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa have added layers of complexity to the workforce and culture of Baltimore, as well as the religious and ethnic fabric of the city. Baltimore's culture has been described as "the blending of Southern culture and [African-American] migration, Northern industry, and the influx of European immigrants—first mixing at the port and its neighborhoods...Baltimore’s character, it’s uniqueness, the dialect, all of it, is a kind of amalgamation of these very different things coming together—with a little Appalachia thrown in...It’s all threaded through these neighborhoods", according to the American studies academic Mary Rizzo.

As of 2008, the sixty thousand ethnic Koreans in Greater Los Angeles constituted the largest Korean community in the United States. Their number made up 15 percent of the country's Korean American population.

The history of the Russians in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. The Russian community is a growing population and constitutes a major source of new immigrants to the city. Historically the Russian community was centered in East Baltimore, but most Russians now live in Northwest Baltimore's Arlington neighborhood and in Baltimore's suburb of Pikesville.

As of the 2000 U.S. Census there were 45,000 South Korean-origin people in the Chicago metropolitan area. As of 2006 the largest groups of Koreans are in Albany Park, North Park, West Ridge, and other communities near Albany Park. By that time many Koreans began moving to northern and northwestern Chicago suburbs, settling in Glenview, Morton Grove, Mount Prospect, Niles, Northbrook, Schaumburg, and Skokie. A Koreatown, labeled "Seoul Drive", exists along Lawrence Avenue between Kedzie Avenue and Pulaski Road. There are also Korean businesses on Clark Street.

The history of the Hispanics and Latinos in Baltimore dates back to the mid-20th century. The Hispanic and Latino community of Baltimore is the fastest growing ethnic group in the city. There is a significant Hispanic/Latino presence in many Southeast Baltimore neighborhoods, particularly Highlandtown, Upper Fell's Point, and Greektown. Overall Baltimore has a small but growing Hispanic population, primarily in the Southeast portion of the area from Fells Point to Dundalk.

There is a Korean American community in the states of Virginia and Maryland in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. It is the third-largest ethnic Korean community in the United States.

Nick J. Mosby is an American politician in Baltimore, Maryland. He was first elected to serve on the Baltimore City Council. at the age of 32. Mosby served on the Baltimore City Council from December 2011 to December 2016 passing major pieces of legislation like the most progressive form of Ban the Box in the country, addressing proliferation of liquor establishments in high crime and impoverished communities, and working to comprehensively evaluate outdated zoning designations. In January 2017, Mosby was appointed to serve as a member of the Maryland General Assembly in the Maryland House of Delegates representing Baltimore City's 40th District. He was equally successful as a Delegate passing legislation eliminating the draconian practice of selling liens of residents homes for unpaid water bills, developing tax credit programs to strengthen endowments of Maryland's Historically Black Colleges and Universities, requiring the state to allow GED recipients access to over $83 million annual dollars in state higher education scholarships, and passing Ban the Box statewide. Prior to public service, Mosby worked as an electrical engineer managing large scale telecommunication system projects and building multi-million dollar state of the art video cloud storage and computing data centers.