Thomas James Ladnier was an American jazz trumpeter. Hugues Panassié – an influential French critic, jazz historian, and renowned exponent of New Orleans jazz – rated Ladnier, sometime on or before 1956, second only to Louis Armstrong.

George Murphy "Pops" Foster was an American jazz musician, best known for his vigorous slap bass playing of the string bass. He also played the tuba and trumpet professionally.

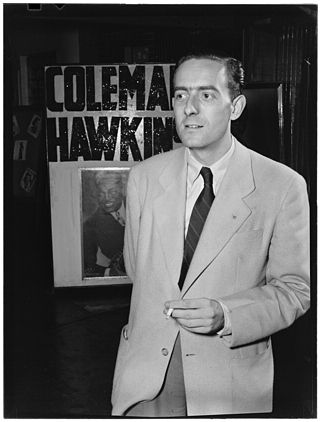

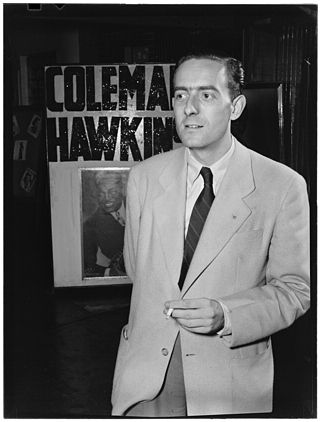

Milton Mesirow, better known as Mezz Mezzrow, was an American jazz clarinetist and saxophonist from Chicago, Illinois. He is remembered for organizing and financing recording sessions with Tommy Ladnier and Sidney Bechet. He recorded with Bechet as well and briefly acted as manager for Louis Armstrong. Mezzrow is equally known as a colorful character, as portrayed in his autobiography, Really the Blues, co-written with Bernard Wolfe and published in 1946.

Arthur James "Zutty" Singleton was an American jazz drummer.

Charles Delaunay was a French author, jazz expert, co-founder and long-term leader of the Hot Club de France.

Arthur W. Hodes, was a Russian Empire-born American jazz and blues pianist. He is regarded by many critics as the greatest white blues pianist.

William C. "Buster" Bailey was an American jazz clarinetist.

The Hot Club de France is a French organization of jazz fans dedicated to the promotion of "traditional" jazz, swing, and blues. It was founded in 1931 in Paris, France, by five students of the Lycée Carnot. In 1928, Jacques Bureaux, Hugues Panassie, Charles Delaunay, Jacques Auxenfans, and Elvin Dirat came together to listen to jazz and, later, promote its acceptance in France. The point was to make the public aware of jazz and to defend and promote the style in the face of all opposition. The club began in the fall of 1931 as the Jazz Club Universitaire, as the members were all still students; it was reborn and reimagined in 1932 as the Hot Club de France.

Guy Lafitte was a French jazz saxophonist.

Will Friedwald is an American author and music critic. He has written for newspapers that include the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Village Voice, Newsday, New York Observer, and New York Sun – and for magazines that include Entertainment Weekly, Oxford American, New York, Mojo, BBC Music Magazine, Stereo Review, Fi, and American Heritage.

Leeds "Lee" Collins was an American jazz trumpeter.

Vernon Brown was an American jazz trombonist.

The Nice Jazz Festival, held annually since 1948 in Nice, on the French Riviera, is "the first jazz festival of international significance." At the inaugural festival, Louis Armstrong and his All Stars were the headliners. Frommer's calls it "the biggest, flashiest, and most prestigious jazz festival in Europe." From 1974 it was known as La Grande Parade du Jazz; in 1980 the name changed to JVC Nice Jazz Festival; since 1993 it has been known as the Nice Jazz Festival.

"Heebie Jeebies" is a composition written by Boyd Atkins which achieved fame when it was recorded by Louis Armstrong in 1926. Armstrong also performed "Heebie Jeebies" as a number at the Vendome Theatre. The recording on Okeh Records by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five includes a famous example of scat singing by Armstrong. After the success of the recording, an accompanying dance was choreographed and advertised by Okeh.

Jive talk, also known as Harlem jive or simply Jive, the argot of jazz, jazz jargon, vernacular of the jazz world, slang of jazz, and parlance of hip is an African-American Vernacular English slang or vocabulary that developed in Harlem, where "jive" (jazz) was played and was adopted more widely in African-American society, peaking in the 1940s.

Coot Grant was an American classic female blues, country blues, and vaudeville singer and songwriter. On her own and with her husband and musical partner, Wesley "Kid" Wilson, she was popular with African American audiences from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Wesley Shellie Wilson, often credited as Kid Wilson, was an American blues and jazz singer and songwriter. His stagecraft and performances with his wife and musical partner, Coot Grant, were popular with African American audiences in the 1910s, 1920s and early 1930s.

Jimmy Ryan's was a jazz club in New York City, USA, located at 53 West 52nd Street from 1934 to 1962 and 154 West 54th Street from 1962–1983. It was a venue for performances of Dixieland jazz.

Jazz Hot is a French quarterly jazz magazine published in Marseille. It was founded in March 1935 in Paris.

Ford Lee "Buck" Washington was an American vaudeville performer, pianist, and singer. He was best known as half of the duo Buck and Bubbles, who were the first black artists to appear on television, with John W. Bubbles, his performance partner for 40 years.