Gamelan is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. The most common instruments used are metallophones and a set of hand-drums called kendang, which keep the beat. The kemanak, a banana-shaped idiophone, and the gangsa, another metallophone, are also commonly used gamelan instruments on Bali. Other notable instruments include xylophones, bamboo flutes, a bowed string instrument called a rebab, and a zither-like instrument called a siter, used in Javanese gamelan. Additionally, vocalists may be featured, being referred to as sindhen for females or gerong for males.

| conven Siege of Johor (1567) | common_name = Majapahit

Central Java is a province of Indonesia, located in the middle of the island of Java. Its administrative capital is Semarang. It is bordered by West Java in the west, the Indian Ocean and the Special Region of Yogyakarta in the south, East Java in the east, and the Java Sea in the north. It has a total area of 34,337.48 km2, with a population of 36,516,035 at the 2020 Census making it the third-most populous province in both Java and Indonesia after West Java and East Java. The official population estimate in mid-2022 was 37,032,410. The province also includes a number of offshore islands, including the island of Nusakambangan in the south, and the Karimun Jawa Islands in the Java Sea.

The kris or keris is a Javanese asymmetrical dagger with a distinctive blade-patterning achieved through alternating laminations of iron and nickelous iron (pamor). The kris is famous for its distinctive wavy blade, although many have straight blades as well, and is one of the weapons commonly used in the pencak silat martial art native to Indonesia. Kris have been produced in many regions of Indonesia for centuries, but nowhere—although the island of Bali comes close—is the kris so embedded in a mutually-connected whole of ritual prescriptions and acts, ceremonies, mythical backgrounds and epic poetry as in Central Java. Within Indonesia the kris is commonly associated with Javanese culture, although other ethnicities in it and surrounding regions are familiar with the weapon as part of their cultures, such as the Balinese, Sundanese, Malay, Madurese, Banjar, Buginese, and Makassar people. The kris itself is considered as a cultural symbol of Indonesia and also neighbouring countries like Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand.

The culture of Indonesia has been shaped by long interaction between original indigenous customs and multiple foreign influences. Indonesia is centrally-located along ancient trading routes between the Far East, South Asia and the Middle East, resulting in many cultural practices being strongly influenced by a multitude of religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, and Islam, all strong in the major trading cities. The result is a complex cultural mixture, often different from the original indigenous cultures.

Rangda is the demon queen of the Leyaks in Bali, according to traditional Balinese mythology. Terrifying to behold, the child-eating Rangda leads an army of evil witches against the leader of the forces of good — Barong. The battle between Barong and Rangda is featured in a Barong dance which represents the eternal battle between good and evil.

Wayang wong, also known as wayang orang, is a type of classical Javanese and Balinese dance theatrical performance with themes taken from episodes of the Ramayāna or Mahabharāta. Performances are stylised, reflecting Javanese court culture:

Wayang wong dance drama in the central Javanese Kraton of Yogyakarta represents the epitome of Javanese aesthetic unity. It is total theatre involving dance, drama, music, visual arts, language, and literature. A highly cultured sense of formality permeates every aspect of its presentation.

Dance in Indonesia reflects the country's diversity of ethnicities and cultures. There are more than 1,300 ethnic groups in Indonesia. Austronesian roots and Melanesian tribal forms are visible, and influences ranging from neighboring Asian and even western styles through colonization. Each ethnic group has its own dances: there are more than 3,000 original dance forms in Indonesia. The old traditions of dance and drama are being preserved in the many dance schools which flourish not only in the courts but also in the modern, government-run or supervised art academies.

Javanese literature is, generally speaking, literature from Java and, more specifically, from areas where Javanese is spoken. However, similar with other literary traditions, Javanese language works were and not necessarily produced only in Java, but also in Sunda, Madura, Bali, Lombok, Southern Sumatra and Suriname. This article only deals with Javanese written literature and not with oral literature and Javanese theatre such as wayang.

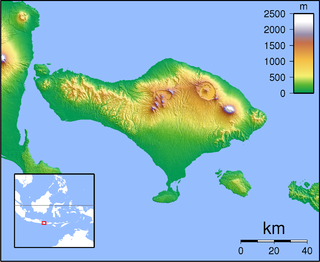

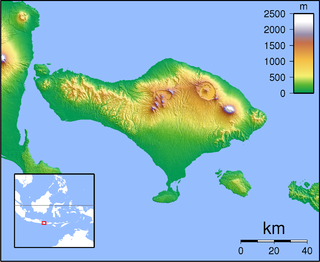

The History of Bali covers a period from the Paleolithic to the present, and is characterized by migrations of people and cultures from other parts of Asia. In the 16th century, the history of Bali started to be marked by Western influence with the arrival of Europeans, to become, after a long and difficult colonial period under the Dutch, an example of the preservation of traditional cultures and a key tourist destination.

Joe Cribb is a numismatist, specialising in Asian coinages, and in particular on coins of the Kushan Empire. His catalogues of Chinese silver currency ingots, and of ritual coins of Southeast Asia were the first detailed works on these subjects in English. With David Jongeward he published a catalogue of Kushan, Kushano-Sasanian and Kidarite Hun coins in the American Numismatic Society New York in 2015. In 2021 he was appointed Adjunct Professor of Numismatics at Hebei Normal University, China.

Javanisation or Javanization is the process in which Javanese culture dominates, assimilates, or influences other cultures in general. The term "Javanise" means "to make or to become Javanese in form, idiom, style, or character". This domination could take place in various aspects; such as cultural, language, politics and social.

The Kingdomship of Bali was a series of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms that once ruled some parts of the volcanic island of Bali, in Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia. With a history of native Balinese kingship spanning from the early 10th to early 20th centuries, Balinese kingdoms demonstrated sophisticated Balinese court culture where native elements of spirit and ancestral reverence combined with Hindu influences—adopted from India through ancient Java intermediary—flourished, enriched and shaped Balinese culture.

Wayang kulit is a traditional form of shadow puppetry originally found in the cultures of Java and Bali in Indonesia. In a wayang kulit performance, the puppet figures are rear-projected on a taut linen screen with a coconut oil light. The dalang manipulates carved leather figures between the lamp and the screen to bring the shadows to life. The narratives of wayang kulit often have to do with the major theme of good vs. evil.

It is quite difficult to define Indonesian art, since the country is immensely diverse. The sprawling archipelago nation consists of 17.000 islands. Around 922 of those permanently inhabited, by over 1,300 ethnic groups, which speak more than 700 living languages.

The makuṭa, variously known in several languages as makuta, mahkota, magaik, mokot, mongkut or chada, is a type of headdress used as crowns in the Southeast Asian monarchies of today's Cambodia and Thailand, and historically in Java and Bali (Indonesia), Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Laos and Myanmar. They are also used in classical court dances in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand; such as khol, khon, the various forms of lakhon, as well as wayang wong dance drama. They feature a tall pointed shape, are made of gold or a substitute, and are usually decorated with gemstones. As a symbol of kingship, they are featured in the royal regalia of both Cambodia and Thailand.

Kemben is an Indonesian female torso wrap historically common in Java, Bali, and other parts of the Indonesian archipelago. It is made by wrapping a piece of kain (clothes), either plain, batik printed, velvet, or any type of fabrics, covering the chest wrapped around the woman's torso.

By the 10th-century, Java had one of the most complex economies in Southeast Asia. Despite the importance of rice farming which acts as the chief tax income for the Javanese courts, the influx of sea trade in Asia between the 10th and 13th centuries forced a more convenient currency to the Javanese economy. During the late 8th-century, ingots made of gold and silver were introduced. These are the early Nusantara coins.

The cash coins of Indonesia was a historical currency in Indonesia based on Chinese imperial coinage during the Tang dynasty era. It was introduced by the Chinese traders, but did not become popular in Indonesia until Singhasari defeated the Mongol empire in 13th century. Chinese cash coins continued to circulate in Indonesian archipelago for centuries; when the Ming dynasty banned trade with the region, many local rulers started creating their own imitations of Chinese cash coins which were often thinner and of inferior quality. Cash coins produced in Indonesia were made from various materials such as copper-alloys, lead, and most commonly tin.