Jiaochao (simplified Chinese :交钞; traditional Chinese :交鈔; pinyin :jiāochāo) is a Chinese word for banknote first used for the currency of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty and later by the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China.

Jiaochao (simplified Chinese :交钞; traditional Chinese :交鈔; pinyin :jiāochāo) is a Chinese word for banknote first used for the currency of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty and later by the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China.

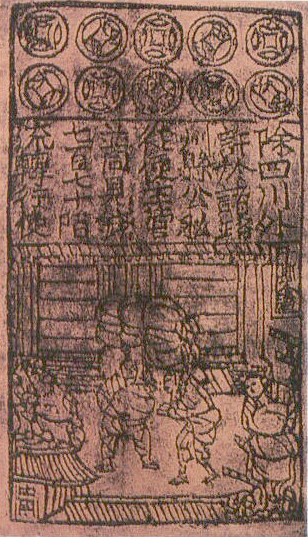

The Jurchens swept control over northern China, conquering the Liao dynasty and half of the Song dynasty by 1142. Initially they did not have a unique currency of their own but reused the coinage of the Liao or Southern Song dynasty coinage. In 1154, Wanyan Liang issued the Jiaochao banknotes three years before minting their own distinct coinage, a sequence in Chinese history that has never happened before or since. Jiaochao came in ten denominations. Small bills came in 100, 200, 300, 500, and 700 wén while large bills were in 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 guàn . Like previous Chinese notes, there was a fee for redeeming them for copper coins: 15 wén per guàn. Jiaochao initially had an expiration period of seven years upon issue but in 1189 this was abolished, giving notes an indefinite lifespan. Like other early Chinese paper currencies, it was a victim of overprinting which led to runaway inflation. In 1214, due to severe hyperinflation, the government began printing notes worth up to 1000 guàn. The following year, Jiaochao was replaced with a new paper currency the Baoquan (寶泉) which suffered the same fate. Up until the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty in 1234, the state kept releasing new types of banknotes which were rejected by the public who were only willing to accept transactions in silver. [1] : 9–33

Jin and Song notes continued to circulate in territories conquered by the Mongols. In 1227, during the last year of Genghis Khan's life, he had silk-backed imitation Huizi printed. Sorghaghtani Beki, Ögedei Khan, Güyük Khan, and Möngke Khan issued various paper scrips for their occupational armies. [1] : 37

In 1260, the first year of Kublai Khan's rule, he issued two different Jiaochao notes. The first in July was backed by silk but was unsuccessful. The second was in October which used the silver standard. [1] : 37 It was the first paper currency to be used as the predominant circulating medium in the history of China. [2] The primary press was the Imperial Mint established in 1260, probably in Yanjing. It was certainly located in Khanbaliq after that city was established the same decade. Regional capitals were sometimes authorized to print money as well. The money of the various eras of the Yuan were also separately known, as the Zhongtong notes and Zhiyuan notes of the reign of Kublai Khan. [3] They too suffered from devaluation and hyperinflation. In 1350 the final series of banknotes, the Zhizheng Jiaochao (至正交鈔) was issued. Unlike earlier notes, this was a fiat currency and was widely rejected. [1] : 35–76

Jiaochao was described by the a number of foreign visitors, including Rustichello in his account of the travels of the Venetian Marco Polo, [4] by William of Rubruck, and by Ibn Battuta. [5]

The people of China do not do business for dinars and dirhams. In their country all the gold and silver they acquire they melt down into ingots, as we have said. They buy and sell with pieces of paper the size of the palm of the hand which are stamped with the Sultan's stamp. Twenty-five such pieces are called balisht, which is the same as dinar among us. If these pieces of paper become tattered from handling they take them to a house which is like our mint and receive new ones instead. The new pieces are not given against payment of any kind, for those in charge of this work receive regular salaries from the Sultan. The amir in charge of that house is one of the most important. If anyone goes to the bazaar with a silver dirham or a dinar intending to buy something with it, it is not accepted and he is disregarded until he pays with a balisht and buys what he wants. [6]

Later in 1294, in order to control the treasury, Gaykhatu of the Ilkhanate in Persia attempted to introduce paper money in his khanate, which imitated the notes issued by the Yuan dynasty so closely that they even had Chinese words printed on them. However, the experiment proved to be a complete failure, and Gaykhatu was assassinated shortly afterward. [7]

Paper money, often referred to as a note or a bill, is a type of negotiable promissory note that is payable to the bearer on demand, making it a form of currency. The main types of paper money are government notes, which are directly issued by political authorities, and banknotes issued by banks, namely banks of issue including central banks. In some cases, paper money may be issued by other entities than governments or banks, for example merchants in pre-modern China and Japan. "Banknote" is often used synonymously for paper money, not least by collectors, but in a narrow sense banknotes are only the subset of paper money that is issued by banks.

Möngke Khan was the fourth khagan of the Mongol Empire, ruling from 1 July 1251 to 11 August 1259. He was the first Khagan from the Toluid line, and made significant reforms to improve the administration of the Empire during his reign. Under Möngke, the Mongols conquered Iraq and Syria as well as the kingdom of Dali.

Külüg Khan, born Khayishan, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Wuzong of Yuan, was an emperor of the Yuan dynasty of China. Apart from being the Emperor of China, he is regarded as the seventh Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, although it was only nominal due to the division of the empire. His regnal name "Külüg Khan" means "warrior Khan" or "fine horse Khan" in the Mongolian language.

The Manchukuo yuan was the official unit of currency of the Empire of Manchuria, from June 1932 to August 1945.

The history of Chinese currency spans more than 3000 years from ancient China to imperial China and modern China. Currency of some type has been used in China since the Neolithic age which can be traced back to between 3000 and 4500 years ago. The history of China's monetary system traces back to the Shang Dynasty, where cowrie shells served as early currency. Cowry shells are believed to have been the earliest form of currency used in Central China, and were used during the Neolithic period. By the Warring States Period, diverse metal currencies like knife and spade coins emerged. These early currencies, starting as a commodity exchange to cowrie shells, copper coins, paper money and modern chinese currencies and digital currencies shows how centralized power developed the most influential monetary system in the world.

Mongols living within the Mongol Empire (1206–1368) maintained their own culture, not necessarily reflective of the majority population of the historical Mongolian empire, as most of the non-Mongol peoples inside it were allowed to continue their own social customs. The Mongol class largely lead separate lives, although over time there was a considerable cultural influence, especially in Persia and China.

Bolad, was an ethnic Mongol minister of the Yuan dynasty of China, and later served in the Ilkhanate as the representative of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire and cultural adviser to the Ilkhans. He also provided valuable information to Rashid-al-Din Hamadani to write about the Mongols. Mongolists consider him a cultural bridge between East and West. He was ennobled by Emperor Renzong of Yuan as Duke of Ze (澤國公) in 1311 and Prince of Yongfeng (永豐郡王) in 1313, posthumously.

The Yuan dynasty, officially the Great Yuan, was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire from the Borjigin clan, and lasted from 1271 to 1368. In Chinese history, the Yuan dynasty followed the Song dynasty and preceded the Ming dynasty.

Fiat money is a type of government issued currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity. Fiat currency is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender, and is authorized by government regulation. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1975, the major currencies in the world are fiat money.

The Yuan dynasty was a Mongol-ruled Chinese dynasty which existed from 1271 to 1368. After the conquest of the Western Xia, Western Liao, and Jin dynasties they allowed for the continuation of locally minted copper currency, as well as allowing for the continued use of previously created and older forms of currency, while they immediately abolished the Jin dynasty's paper money as it suffered heavily from inflation due to the wars with the Mongols. After the conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, the Yuan dynasty started issuing their own copper coins largely based on older Jin dynasty models, though eventually the preferred Yuan currency became the Jiaochao and silver sycees, as coins would eventually fall largely into disuse. Although the Mongols at first preferred to have every banknote backed up by gold and silver, high government expenditures forced the Yuan to create fiat money in order to sustain government spending.

The Southern Song dynasty refers to an era of the Song dynasty after Kaifeng was captured by the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty in 1127. The government of the Song was forced to establish a new capital city at Lin'an which wasn't near any sources of copper so the quality of the cash coins produced under the Southern Song significantly deteriorated compared to the cast copper-alloy cash coins of the Northern Song dynasty. The Southern Song government preferred to invest in their defenses while trying to remain passive towards the Jin dynasty establishing a long peace until the Mongols eventually annexed the Jin before marching down to the Song establishing the Yuan dynasty.

The Jin dynasty was a Jurchen-led dynasty of China that ruled over northern China and Manchuria from 1115 until 1234. After the Jurchens defeated the Liao dynasty and the Northern Song dynasty, they would continue to use their coins for day to day usage in the conquered territories. In 1234, they were conquered by the Mongol Empire.

During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) of China, many scientific and technological advancements were made in areas such as mathematics, medicine, printing technology, and gunpowder warfare.

The Great Ming Treasure Note or Da Ming Baochao was a series of banknotes issued during the Ming dynasty in China. They were first issued in 1375 under the Hongwu Emperor. Although initially the Great Ming Treasure Note paper money was successful, the fact that it was a fiat currency and that the government largely stopped accepting these notes caused the people to lose faith in them as a valid currency causing the price of silver relative to paper money to increase. The negative experiences with inflation that the Ming dynasty had witnessed signaled the Manchus to not repeat this mistake until the first Chinese banknotes after almost 400 years were issued again in response to the Taiping Rebellion under the Qing dynasty's Xianfeng Emperor during the mid-19th century.

The paper money of the Qing dynasty was periodically used alongside a bimetallic coinage system of copper-alloy cash coins and silver sycees; paper money was used during different periods of Chinese history under the Qing dynasty, having acquired experiences from the prior Song, Jin, Yuan, and Ming dynasties which adopted paper money but where uncontrolled printing led to hyperinflation. During the youngest days of the Qing dynasty paper money was used but this was quickly abolished as the government sought not to repeat history for a fourth time; however, under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor, due to several large wars and rebellions, the Qing government was forced to issue paper money again.

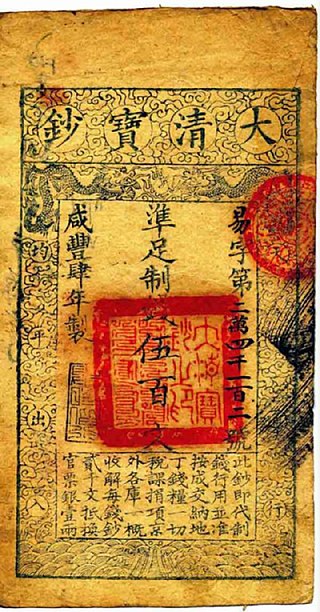

The Great Qing Treasure Note or Da-Qing Baochao refers to a series of Qing dynasty government notes issued under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor issued between the years 1853 and 1859. These government notes were all denominated in wén and were usually introduced to the general market through the salaries of soldiers and government officials.

The Hubu Guanpiao is the name of two series of government notes produced by the Qing dynasty, the first series was known as the Chaoguan (鈔官) and was introduced under the Shunzhi Emperor during the Qing conquest of the Ming dynasty but was quickly abandoned after this war ended, it was introduced amid residual ethnic Han resistance to the Manchu invaders. These government notes were produced on a small scale, amounting to 120,000 strings of cash coins annually, and only lasted between 1651 and 1661. After the death of the Shunzhi Emperor in the year 1661, calls for resumption of note issuance weakened, although they never completely disappeared.

A string of cash coins refers to a historical Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, and Vietnamese currency unit that was used as a superunit of the Chinese cash, Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn currencies. The square hole in the middle of cash coins served to allow for them to be strung together in strings. The term would later also be used on banknotes and served there as a superunit of wén (文).

The banknotes of the Da-Qing Bank were intended to become the main form of paper money of the Qing dynasty following the bank's establishment in 1905. The Da-Qing Bank had branches throughout China and many of its branches outside of its headquarters in Beijing also issued banknotes.

Daqian are large-denomination cash coins produced in the Qing dynasty starting from 1853 until 1890. Large denomination cash coins were previously used in earlier Chinese dynasties and had faced similar issues as 19th-century Daqian. The term referred to cash coins with a denomination of 4 wén or higher.