Related Research Articles

Storyville was the red-light district of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1897 to 1917. It was established by municipal ordinance under the New Orleans City Council, to regulate prostitution. Sidney Story, a city alderman, wrote guidelines and legislation to control prostitution within the city. The ordinance designated an area of the city in which prostitution, although still nominally illegal, was tolerated or regulated. The area was originally referred to as "The District", but its nickname, "Storyville", soon caught on, much to the chagrin of Alderman Story. It was bound by the streets of North Robertson, Iberville, Basin, and St. Louis Streets. It was located by a train station, making it a popular destination for travelers throughout the city, and became a centralized attraction in the heart of New Orleans. Only a few of its remnants are now visible. The neighborhood lies in Faubourg Tremé and the majority of the land was repurposed for public housing. It is well known for being the home of jazz musicians, most notably Louis Armstrong as a minor.

James Bowie was a 19th-century American pioneer, slave smuggler and trader, and soldier who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He was among the Americans who died at the Battle of the Alamo. Stories of him as a fighter and frontiersman, both real and fictitious, have made him a legendary figure in Texas history and a folk hero of American culture.

A Bowie knife is a pattern of fixed-blade fighting knife created by Rezin Bowie in the early 19th century for his brother James Bowie, who had become famous for his use of a large knife at a duel known as the Sandbar Fight.

Roosevelt Sykes was an American blues musician, also known as "the Honeydripper".

Bourbon Street is a historic street in the heart of the French Quarter of New Orleans. Extending twelve blocks from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue, Bourbon Street is famous for its many bars and strip clubs.

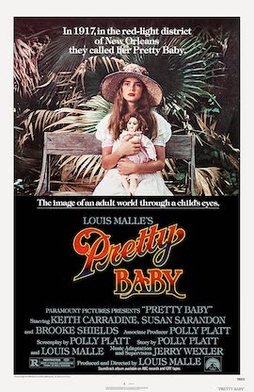

Pretty Baby is a 1977 American historical drama film directed by Louis Malle, written by Polly Platt, and starring Brooke Shields, Keith Carradine, and Susan Sarandon. Set in 1917, it focuses on a 12-year-old girl being raised in a brothel in Storyville, the red-light district of New Orleans by her prostitute mother. Barbara Steele, Diana Scarwid, and Antonio Fargas appear in supporting roles. The film is based on the true account of a young girl who was sexually exploited by being forced into prostitution by her mother, which was recounted in historian Al Rose's 1974 book Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District, as well as the life of photographer Ernest Bellocq, who photographed various New Orleans prostitutes in the early-twentieth century. Its title is derived from the Tony Jackson song of the same name, which is used in the soundtrack.

The Levee District was the red-light district of Chicago from the 1880s until 1912, when police raids shut it down. The district, like many frontier town red-light districts, got its name from its proximity to wharves in the city. The Levee district encompassed four blocks in Chicago's South Loop area, between 18th and 22nd streets. It was home to many brothels, saloons, dance halls, and the famed Everleigh Club. Prostitution boomed in the Levee District, and it was not until the Chicago Vice Commission submitted a report on the city's vice districts that it was shut down.

Lulu White was a brothel madam, procuress and entrepreneur in New Orleans, Louisiana during the Storyville period. An eccentric figure, she was noted for her love of jewelry, her many failed business ventures, and her criminal record that extended in New Orleans as far back as 1880.

Minnie White was an American brothel owner in Storyville, New Orleans in the early part of the twentieth century. She operated out of a large mansion at 221 North Basin Street, in New Orleans, Louisiana, between 1907 and 1917. The brothel closed when, under pressure from The War and Navy Department, Mayor Martin Behrman closed Storyville. For most or all of that time, she co-owned the structure with another madam, Jessie Brown. A 1911-12 edition of the Storyville Blue Book indicates that the phone number of White's establishment was 1663 Main.

Hilma Burt was an American brothel madam in Storyville, New Orleans, Louisiana during the early twentieth century. This area, originally known as "The District", permitted legalized prostitution from 1897 to 1917 and became possibly the best known area for prostitution in the nation.

Josie Arlington was a brothel madam in the Storyville district of New Orleans, Louisiana. Arlington started her life as a prostitute at 17–18 years old as a means to support her family. Arlington used her experience to open a brothel in 1890, which she named "Chateau Lobrano d'Arlington". Shortly after Storyville was established as the red-light district for New Orleans, Arlington moved her business into this area. After her building was destroyed by fire in 1905 she moved her business into a saloon owned by Tom Anderson, which was known as 'The Arlington Annex'. Josie retired from the business in 1909 and sold her assets off to Tom Anderson. Arlington died in 1913 and was buried in Metairie Cemetery, where her grave had to be moved because it had become such a tourist attraction.

The Iron Mistress is a 1952 American Western film directed by Gordon Douglas and starring Alan Ladd and Virginia Mayo. It ends with Bowie's marriage to Ursula de Veramendi and does not deal with his death at the Battle of the Alamo in 1836.

Ripper Street is a British mystery drama television series set in Whitechapel in the East End of London starring Matthew Macfadyen, Jerome Flynn, Adam Rothenberg, and MyAnna Buring. It begins in 1889, six months after the infamous Jack the Ripper murders. The first episode was broadcast on 30 December 2012, during BBC One's Christmas schedule, and was first broadcast in the United States on BBC America on 19 January 2013. Ripper Street returned for a second eight-part series on 28 October 2013.

Julia Jackson was a Louisiana Voodoo practitioner from New Orleans.

Willie Vincent Piazza was a sex worker and brothel proprietor in the Storyville during that red light district's period of legal operation. From 1898 until the district's closure in 1917, Piazza worked as a madam and specialized in providing octoroon women for her clients; she herself was mixed-race.

Thomas Anderson (1858–1931) was a political boss and state legislator, and the unofficial "mayor" of Storyville in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Ann Cook was an American blues and gospel singer. Born and raised in rural Louisiana, Cook moved to New Orleans as a teenager. She served as a prostitute and singer in the Storyville neighborhood, living in an area known as "The Battlefield".

Clementine Barnabet was an accused American serial killer who was convicted of killing one person and confessed to have killed as many as 35. However, doubt has since been cast on her involvement.

New Orleans: the Storyville Musical is a musical by Toni Morrison, Donald McKayle and Dorothea Freitag, set in 1917 in New Orleans' Storyville district. Produced in workshop in 1982, it also received staged readings at New York Shakespeare Festival in 1984 but was never fully produced. It was Morrison's first venture in the medium of theatre.

References

- ↑ Rose 1974, preface.

- ↑ deClouet 1999, pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Taylor 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Storyville Madams". www.storyvilledistrictnola.com. Storyville: New Orleans. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- 1 2 Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, p. 41.

- ↑ deClouet 1999, p. 22.

- 1 2 "Early Mansions, New Orleans". www.storyvilledistrictnola.com. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ↑ deClouet 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Goodman 2005, p. 156.

- ↑ Goodman 2005, p. 157.

- ↑ deClouet 1999, p. 30.

- ↑ Goodman 2005, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Goodman 2005, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Goodman 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ deClouet 1999, pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 3 4 deClouet 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, p. 44.

- ↑ Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Gauthreaux & Hippensteel 2015, pp. 49–50.