The Shamkhalate of Tarki, or Tarki Shamkhalate was a Kumyk state in the eastern part of the North Caucasus, with its capital in the ancient town of Tarki. It formed on the territory populated by Kumyks and included territories corresponding to modern Dagestan and adjacent regions. After subjugation by the Russian Empire, the Shamkhalate's lands were split between the Empire's feudal domain with the same name extending from the river Sulak to the southern borders of Dagestan, between Kumyk possessions of the Russian Empire and other administrative units.

The Malkhi were an ancient nation, living in the Western/Central North Caucasus, mentioned in classical sources, primarily by ancient Greco-Syrian writer Lucian and ancient Roman writer Claudius Aelianus.

Syunik was a region of historical Armenia and the ninth province of the Kingdom of Armenia from 189 BC until 428 AD. From the 7th to 9th centuries, it fell under Arab control. In 821, it formed two Armenian principalities: Kingdom of Syunik and principality of Khachen, which around the year 1000 was proclaimed the Kingdom of Artsakh, becoming one of the last medieval eastern Armenian kingdoms and principalities to maintain its autonomy following the Turkic invasions of the 11th to 14th centuries.

Terki fortress, Terka, or Terek was a Russian fortress in the Caucasus in the 16-18th centuries. It was originally erected at the mouth of the Sunzha river on the lands of the Tyumen Khanate, it was demolished several times, restored and transferred.

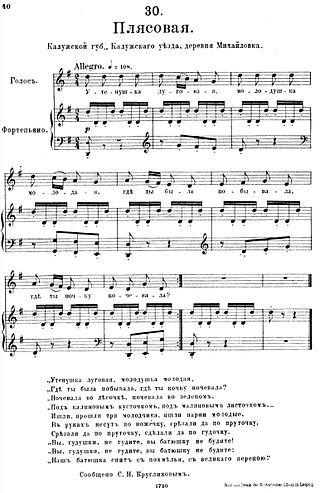

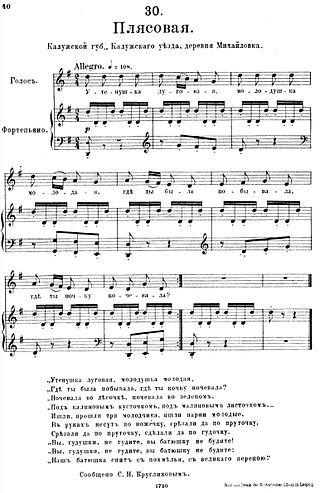

"Utushka lugovaya" is an ancient Russian folk song.

Talkhig of Shali was a 19th-century commander from the Northern Caucuses. A native of Shali and a representative of the taip Kurchaloy, he was a military leader and statesman of the North Caucasian Imamate. He was also a mudir (general-naib) and head of artillery of the North Caucasian Imamate, as well as a naib of the districts of Shali and Greater Chechnya.

Kizlyar Brandy Factory is a Russian producer of alcoholic beverages, located in Kizlyar, Dagestan. It is one of the five largest Russian brandy producers.

Kumykia, or rarely called Kumykistan, is a historical and geographical region located along the Caspian Sea shores, on the Kumyk plateau, in the foothills of Dagestan and along the river Terek. The term Kumykia encompasses territories which are historically and currently populated by the Turkic-speaking Kumyk people. Kumykia was the main "granary of Dagestan". The important trade routes, such as one of the branches of the Great Silk Road, passed via Kumykia.

The Komi language, a Uralic language spoken in the north-eastern part of European Russia, has been written in several different alphabets. Currently, Komi writing uses letters from the Cyrillic script. There have been five distinct stages in the history of Komi writing:

Aldaman Gheza was a Chechen feudal lord that lived in the Chebarla (Cheberloy) region of Chechnya in the 17th century. He is a prominent figure in the region, Chechen and Ingush folklores, and celebrated as a hero that protected the Chechen borders from foreign invasions. For example, the victory at the Battle of Khachara is attributed to him as he supposedly led the Chechen forces in the battle against Avar Khanate.

The Kashin Bridge is a hingeless vault bridge across the Kryukov Canal in the Admiralteysky District of Saint Petersburg, Russia. The bridge connects Kolomensky and Kazansky Islands.

Since its inception in the 18th century and up to the present, it is based on the Cyrillic alphabet to write the Udmurt language. Attempts were also made to use the Latin alphabet to write the Udmurt language. In its modern form, the Udmurt alphabet was approved in 1937.

Iktul Distillery is a Russian distiller based in Sokolovo, Zonalny District, Altai Krai. Founded in 1868, it's the oldest distillery in Eastern Siberia.

Zangezur is a historical and geographical region in Eastern Armenia on the slopes of the Zangezur Mountains which largely corresponds to the Syunik Province of Armenia. It was ceded to Russia by Qajar Iran according to the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. In Soviet times, the Goris, Kapan, Meghri and Sisian regions of the Armenian SSR were located within Zangezur, which in 1995 became part of the Syunik Province of Armenia.

Narchat, Narchatka, Naricha was a Moksha Queen, ruler of Moxel mentioned in Russian sources as Murunza. She was daughter and successor of king Puresh and sister of Atämaz. She led the uprising against Mongols in 1242 and was slain in Battle of Sernya in 1242.

The Dzherakh, also spelled Jerakh, historically also known as Erokhan people, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society, today a tribal organization/clan (teip), that was formed in the Dzheyrakhin gorge, as well as in the area of the lower reaches of the Armkhi River and the upper reaches of the Terek River.

Khamkhins, also known as Ghalghaï, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society, which was located in the upper reaches of the Assa River. The Khamkhin society, like the Tsorin society, was formed from the former "Ghalghaï society" as a result of the transfer of rural government to Khamkhi.

Tsorins, Tsori, also Ghalghaï, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society that was located in mountainous Ingushetia in the region of river Guloykhi. The center of the society was Tsori from which it got its name. Tsorin society, like the Khamkhin society, was formed from the former "Galgaï society" as a result of the transfer (appearance) of rural government to the village Tsori.

Tashaw-Hadji was one of the prominent leaders of the North Caucasian resistance during the Caucasian War, a companion of imam Shamil. He was the imam of Chechnya since 1834. Upon the death of Gazi-Muhammad, he was one of the major candidates at the elections of the Imam of Dagestan, losing to Shamil by one vote only. Later, he became one of the mudirs of Imam Shamil. He was also the governor (naib) of Aukh.

World Music Cultures Center is a scientific and creative center at the Moscow State Conservatory, which conducts scientific, informational, organizational, concert, festival and educational activities. The scientific and creative center organizes festivals and conducts master classes with famous performers of traditional music from around the world.