Plot

About to be executed for a crime he never committed, Boris Grushenko recalls how he got into his present predicament. Initially scheduled to die at 5:00 am, Boris receives leniency—a delay in execution until 6:00 am.

While his brothers Ivan and Mikhail are brawny and athletic, Boris is scrawny and 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) tall. Since childhood, Boris has been in love with his cousin Sonja, with whom he has deep philosophical conversations. Sonja tells Boris that she yearns for a man who embodies the three essential aspects of love: intellectuality, spirituality, and sensuality. Thinking that she is confessing her love for him, Boris is devastated when Sonja reveals she has been in love with the dim-witted Ivan all her life.

When Napoleon invades Austria during the Napoleonic Wars, Boris, a pacifist who would rather write poetry than go to war, is branded a coward by everyone, including his parents and Sonja, who force him to enlist in the Russian army. When Ivan announces his intention to marry Anna Ivanova, a desolate Sonja impulsively announces that she will marry 81-year-old Sergei Minskov, who immediately dies from a heart attack. Sonja then marries Leonid Boskovic, the herring merchant, who amuses himself with herring while Sonja dallies with a musician.

Boris completes military training, including a "hygiene play" on condoms and venereal diseases. During a three-day furlough, Boris attends the opera in Saint Petersburg and flirts with the beautiful Countess Alexandrovna, whose current lover has killed several of her admirers in duels.

Unhappy in her marriage to Boskovic, Sonja recounts a long list of lovers. Boris offers to take her away, but Sonja only asks after Ivan. At the front line the next day, Boris inadvertently becomes a war hero when he falls asleep inside a large cannon and is fired into the French command tent, killing the officers. The regiment that started with 12,000 men in battle thins down to 14 survivors. Ivan, a battle fatality, is bayonetted to death by a Polish conscientious objector.

A Turkish cavalry officer impugns Sonja's chastity. Boskovic dies accidentally while cleaning his pistol in preparation for a duel to defend her honor. Sonja laments she was not kinder to him, believing she could have had sex with him even once, but quickly moves on and grieves over Ivan's death with Anna.

After the Countess has sex with Boris in gratitude for his heroic efforts, her lover, Anton Lebedokov, challenges him to a duel. On the night before the duel, Boris proposes to the widowed Sonja, who promises to marry him, predicting that he will die in the duel. To her surprise and dejection, Boris survives the duel. Their marriage is filled with philosophical debates. Sonja believes that sex without love is an empty experience, to which Boris replies, "Yes, but as empty experiences go, it's one of the best." As time passes, he wins Sonja's heart.

As French troops occupy Moscow, Sonja conceives a plot to assassinate Napoleon at his headquarters in Moscow. They debate the matter with philosophical doublespeak, and Boris reluctantly agrees. At an inn en route to Moscow, they encounter Don Francisco and his sister, emissaries from Joseph Bonaparte to Napoleon. Boris and Sonja waylay the Spaniards, taking their place. Unknowingly, they meet with Napoleon's impostor, who attempts to seduce Sonja but is knocked out by her after Boris fails various attempts. Over the unconscious body, Sonja and Boris debate the ethics of killing Napoleon. While Boris vacillates, another intended Napoleon assassin shoots the impostor.

Sonja escapes, but Boris is arrested for the murder. Despite being told by an angelic vision that he will be pardoned, Boris is executed. At home, while sharing her philosophical insights on love and suffering with her friend Natasha Petrovna, Sonja sees Boris' ghost outside her window, standing with Death. Sonja tells Boris that he was her one great love. Boris soliloquizes about his thoughts on God, death, and love before dancing away with Death.

Style

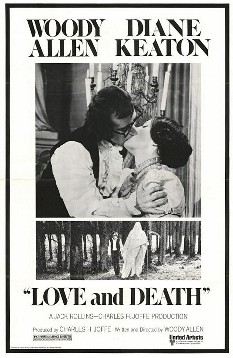

Coming between Allen's Sleeper (1973) and Annie Hall (1977), Love and Death is in many respects an artistic transition between the two. [3] Allen pays tribute to the humor of The Marx Brothers, Bob Hope and Charlie Chaplin throughout the film (for example, the opening narration, “How I got into this predicament, I’ll never know”, is a paraphrase of a punchline from Animal Crackers). [4]

The dialogue and scenarios parody Russian novels, particularly those by Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, such as The Brothers Karamazov , Crime and Punishment , The Gambler , The Idiot and War and Peace . [3] This includes a dialogue between Boris and his father in which each line alludes to, or is composed entirely of, Dostoyevsky titles.

The use of Prokofiev on the soundtrack adds to the Russian flavor of the film. Prokofiev's "Troika" from the Lieutenant Kijé Suite is featured prominently, for the film's opening and closing credits and in selected scenes in the film when a "bouncy" theme is required. [5] The battle scene is accompanied with music from Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky cantata. Boris is marched to his execution to the "March" from Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges . [3] The soundtrack is completed by Prokofiev’s Scythian Suite (it plays when the cannon comes loose) and excerpts from Mozart and Boccherini. [6]

Some of the humor is straightforward; other jokes rely on the viewer's awareness of classic literature or contemporary European cinema. For example, the final shot of Keaton is a reference to Ingmar Bergman's Persona . [3] The sequence with the stone lions is a parody of Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin , while the Russian battle against Napoleon's army heavily parodies the same film's "Odessa steps" sequence. [3] Bergman's The Seventh Seal is parodied several times, including during the climax. [3]

Reception

The film grossed $20.1 million in North America, [2] making it the 18th highest grossing picture of 1975 in North America (theatrical rentals were $5 million). [7]

On Rotten Tomatoes, 26 out of 26 critics gave the film a positive rating, with a 100% rating and an average rating of 9.4/10. The site's consensus reads: "Woody Allen plunks his neurotic persona into a Tolstoy pastiche and yields one of his funniest films, brimming with slapstick ingenuity and a literary inquiry into subjects as momentous as Love and Death". [8] Metacritic , which uses a weighted average , assigned the film a score of 89 out of 100, based on 6 critics, indicating "universal acclaim". [9]

Roger Ebert gave it three and a half stars and wrote: "Miss Keaton is very good in Love and Death, perhaps because here she gets to establish and develop a character, instead of just providing a foil, as she's often done in other Allen films ... There are dozens of little moments when their looks have to be exactly right, and they almost always are. There are shadings of comic meaning that could have gotten lost if all we had were the words, and there are whole scenes that play off facial expressions. It's a good movie to watch just for that reason, because it's been done with such care, love and lunacy." [10]

Gene Siskel awarded a full four stars and wrote: "Woody Allen is simply terrific in Love and Death. To my mind, it's his funniest film. He plays to his greatest strength (gag line dialog) and stays away from what has limited his other movies (an attempt to develop a story)." [11] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "Woody Allen's grandest work" and "side-splitting." [12] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times declared: "Thin but likable just about sums it up." [13] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post found the film "funny with remarkable and delightful consistency." [14] Penelope Gilliatt of The New Yorker thought that Woody Allen and Diane Keaton "have become an unbeatable new team at pacing haywire intellectual backchat. Their style works as if each of them were a less mock-assertive Groucho Marx with a duplicate of him to play against. For such a recklessly funny film, the impression is weirdly serene." [15] Geoff Brown of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that "the occasional longueurs and dud jokes never prove fatal to the movie's overall success; to use the description Boris applies to his father, Woody Allen is a 'major loon' and Love and Death provides a fine showcase for his talent." [16]

Comedian and filmmaker Bill Hader talked about his appreciation of the film, having listed it as one of his favorite films saying: "I love Diane Keaton in this movie so much. My first real movie crush. It's nonstop jokes, but it's played very real and loose, and it has the starkness of a Bergman movie! It's insane, yet it completely works." [17]