Related Research Articles

A manuscript was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has come to be understood to further include any written, typed, or word-processed copy of an author's work, as distinguished from the rendition as a printed version of the same.

In textual studies, a palimpsest is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off in preparation for reuse, in the form of another document. Parchment was made of lamb, calf, or kid skin and was expensive and not readily available, so, in the interest of economy, a page was often re-used by scraping off the previous writing. In colloquial usage, the term palimpsest is also used in architecture, archaeology and geomorphology to denote an object made or worked upon for one purpose and later reused for another; for example, a monumental brass the reverse blank side of which has been re-engraved.

Pedanius Dioscorides, "the father of pharmacognosy", was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of De materia medica —a 5-volume Greek encyclopedia about herbal medicine and related medicinal substances, that was widely read for more than 1,500 years. For almost two millennia Dioscorides was regarded as the most prominent writer on plants and plant drugs.

The Key of Solomon is a pseudepigraphical grimoire attributed to King Solomon. It probably dates back to the 14th or 15th century Italian Renaissance. It presents a typical example of Renaissance magic.

Trotula is a name referring to a group of three texts on women's medicine that were composed in the southern Italian port town of Salerno in the 12th century. The name derives from a historic female figure, Trota of Salerno, a physician and medical writer who was associated with one of the three texts. However, "Trotula" came to be understood as a real person in the Middle Ages and because the so-called Trotula texts circulated widely throughout medieval Europe, from Spain to Poland, and Sicily to Ireland, "Trotula" has historic importance in "her" own right.

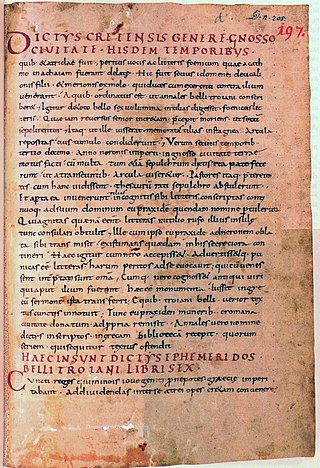

Dictys Cretensis, i.e. Dictys of Crete of Knossos was a legendary companion of Idomeneus during the Trojan War, and the purported author of a diary of its events, that deployed some of the same materials worked up by Homer for the Iliad. The story of his journal, an amusing fiction addressed to a knowledgeable Alexandrian audience, came to be taken literally during Late Antiquity.

On the Soul is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC. His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different operations. Thus plants have the capacity for nourishment and reproduction, the minimum that must be possessed by any kind of living organism. Lower animals have, in addition, the powers of sense-perception and self-motion (action). Humans have all these as well as intellect.

Taqwīm aṣ‑Ṣiḥḥa is originally an 11th-century Arab medical treatise by Ibn Butlan of Baghdad. In the West, the work is known by the Latinized name taken by its translations: TacuinumSanitatis. It is a medieval handbook mainly on health, aimed at a cultured lay audience. The text exists in several variant Latin versions, the manuscripts of which are characteristically so profusely illustrated that one student called the Tacuinum "a [300] picture book", only "nominally a medical text". Numerous European versions were made in increasing numbers in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The Alexander Romance is an account of the life and exploits of Alexander the Great. Although constructed around a historical core, the romance is mostly fictional. It was widely copied and translated, accruing various legends and fantastical elements at different stages. The original version was composed in Ancient Greek some time before 338 CE, when a Latin translation was made, although the exact date is unknown. Several late manuscripts attribute the work to Alexander's court historian Callisthenes, but Callisthenes died before Alexander and therefore could not have written a full account of his life. The unknown author is still sometimes known as Pseudo-Callisthenes.

Pseudo-Apuleius is the name given in modern scholarship to the author of a 4th-century herbal known as Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius or Herbarium Apuleii Platonici. The author of the text apparently wished readers to think that it was by Apuleius of Madaura (124–170 CE), the Roman poet and philosopher, but modern scholars do not believe this attribution. Little or nothing else is known of Pseudo-Apuleius apart from this.

Clavicula may refer to:

The Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis is a collection of craft recipes compiled in Egypt c. 300 AD. It is written in Greek. The Stockholm papyrus has 154 recipes for dyeing, coloring gemstones, cleaning (purifying) pearls, and imitation gold and silver. Certain of them may derive from the Pseudo-Democritus. Zosimos of Panopolis, an Egyptian alchemist of c. 300 AD, gives similar recipes. Some of these recipes are found in medieval Latin collections of technological recipes, notably the Mappae clavicula.

There have been many Coptic versions of the Bible, including some of the earliest translations into any language. Several different versions were made in the ancient world, with different editions of the Old and New Testament in five of the dialects of Coptic: Bohairic (northern), Fayyumic, Sahidic (southern), Akhmimic and Mesokemic (middle). Biblical books were translated from the Alexandrian Greek version.

A biblical manuscript is any handwritten copy of a portion of the text of the Bible. Biblical manuscripts vary in size from tiny scrolls containing individual verses of the Jewish scriptures to huge polyglot codices containing both the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and the New Testament, as well as extracanonical works.

British Library, Add MS 14453, designated by number 66 on the list of Wright, is a Syriac manuscript of the New Testament, on parchment, according to the Peshitta version. Palaeographically it has been assigned to the 5th or 6th century. The manuscript is lacunose. Gregory labelled it by 15e.

The Leyden papyrus X is a papyrus codex written in Greek at about the end of the 3rd century A.D. or perhaps around 250 A.D. and buried with its owner, and today preserved at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

John Greenfield Hawthorne was an English and American archaeologist and academic. He was known for his works on Greek literature, and translations, and in 1963 published, with Cyril Stanley Smith, a translation of the works on metallurgy by Theophilus.

References

- ↑ "Notes on Some Manuscripts of the Mappae Clavicula", by Rozelle P. Johnson, year 1935. A Review of Compositiones variae from Codex 490, Biblioteca Capitolare, by Lynn White, year 1940. Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture, by William Eamon, year 1996, pages 32-36.

- 1 2 3 Mappae clavicula from a 12th-century manuscript, text published in Latin by Thomas Phillipps in year 1847. The original manuscript that Thomas Phillipps possessed, dated late 12th century, is now in the hands of the Corning Museum of Glass. Hence it is referred to as "the Phillipps-Corning manuscript". A digital image of it is downloadable at the Corning Museum of Glass, MS 5.

- 1 2 3 Clarke, M. (2001) The Art of All Colours: Mediaeval Recipe Books for Painters and Illuminators. London: Archetype Publications.

- 1 2 Smith, C. S. and J. G. Hawthorne (1974) ‘Mappae Clavicula: A Little Key to the World of Medieval Techniques’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society: Held at Philadelphia for promoting useful knowledge (new series) 64 (4) [occupies whole issue].

- ↑ Robert Halleux, 'Recettes d'artisan, recettes d'alchimiste', in: R. Jansen-Sieben (ed.) Artes mechanicae, Archives et bibliothèques de Belgique, no. spécial 34 (Brussels, 1989), p. 28

- Sir Thomas Phillipps, "A transcript of a manuscript treatise on the preparation of pigments, and on various processes of the decorative arts practised during the Middle Ages, written in the twelfth century, and entitled Mappae Clavicula." Published in journal Archaeologia, volume XXXII, pages 183–244, year 1847. Downloadable at Archive.org.

- C. S. Smith and J. G. Hawthorne (1974) ‘Mappae Clavicula: A Little Key to the World of Medieval Techniques’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society: Held at Philadelphia for promoting useful knowledge (new series) 64 (4) [occupies whole issue].