Definitions and Concepts

When examining Paul’s work, it is important to make the distinction from modern definitions of words to the definitions used by medieval philosophers and scientists.

Substance – Paul does not use “substance” as the modern definition of “material” or “matter.” Instead, substance describes something that is primary and can exist on its own.

Accident – Paul doesn’t use this term as an unexpected/unplanned event. Instead, it is simply an attribute, or adjective, and cannot exist on its own.

Form/Substantial Form – Form is something that acts on matter that gives it characteristics (e.g. color, hardness, and heaviness). Substantial form is a fundamental type of “form.”

As an example to demonstrate: Substance is simply the object itself, including characteristics that define the object, whereas accidents simply qualify it, but are not necessary for its existence. For example, a bird could be considered the substance, generally combining characteristics such as feathers, a beak, and the ability to lay eggs. Describing a bird as big/small or timid/aggressive simply adds qualification to the bird, but is not defining characteristics of a bird. These concepts of substance and accident stem from Aristotle’s works. [2]

Theorica et practica

Nature and intellect relationship

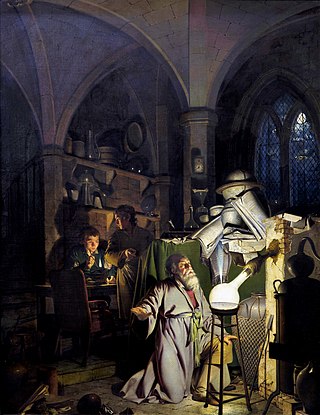

Paul argues that human intellect is superior to nature. Therefore, humans must have the ability to manipulate nature as they see fit. Sculptures and painters, for example, use nature (marble for statue, paint etc) to create various forms of art. They take natural materials and manipulate them in such a way (chiseling a statue, combining colors/drawing shapes, patterns, and figures) to create artistic works. They are able to in a controllable manner alter and improve nature. This thought is also reflected in the act of writing. “[T]he hand does not write by the motion alone of nature, but as ruled by intellect through art.” [3] Artists are able to control nature and use it as a tool or instrument. This concept of intellect over nature is derived from the pseudo-Aristotelian Liber de Causis. [4]

Two categories of arts

Paul then identifies two categories of arts: “Purely artificial” art alters the extrinsic form or “form of art” and “perfective art” alters the “intrinsic” form (or form of nature). Purely artificial art only changes nature superficially, whereas perfective art changes the essence of nature. Paul clarifies this distinction through the use of primary and secondary qualities. The primary qualities are the four Aristotelian qualities, hot, cold, wet, and dry, which reside in the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire). Secondary qualities include white, black, sweet, bitter, hard, soft, sharp, and dull. Perfective art alters the primary qualities, while purely artificial art only results in changes among the secondary qualities; essential changes result from changes in primary qualities, while accidental changes are a result of changes in secondary qualities. A painter and sculpture, then, only practice artificial art since they change shapes and colors of material. Physicians are considered to practice perfective art since they attempt to control the four humors, which by their definition are characterized by the primary qualities. Farmers too, practice perfective art since they work with the transmutation power inherent in seeds. [5] [6] [7]

An analogous modern example of extrinsic versus intrinsic changes is the difference between a physical and chemical reaction. In a physical reaction, there is no change in the molecules in the system. Boiling water is a classic example: The system starts with liquid water, and when enough heat has been added to the water, the water boils into the gaseous phase. While there has been a phase change, the water molecule, H2O hasn’t broken apart and is still present at the end of the reaction, so this is analogous to an extrinsic change. Electrolysis of water is a chemical change – electricity is used to break water into hydrogen and oxygen gas. Since the molecules present have been changed, this is a chemical change, similar to an intrinsic change.

Sulfur-mercury theory of metals

One of the goals of Theorica et practica is to affirm the validity of the sulfur-mercury theory of metals, which basically states that metals are composed of sulfur and mercury and the different proportions between the two form different types of metals. Observations of the reactivity of metals suggest that metals were in fact composed of sulfur and mercury. When metals were heated, they gave off a sulfurous odor. When mercury came in contact with metals such as gold, silver, copper, tin, or lead, an amalgam resulted. These observations lead to the conclusion that metals were composed of both mercury and sulfur. [8] Paul addresses one of the many arguments against the sulfur-mercury theory: that intermediate substances cannot exist between the pure elements and the “final product.” Therefore, metals cannot be broken down into sulfur and mercury. In Theorica et practica, Paul first presents this argument before declining it in a contra and pro fashion. He first states the argument against the sulfur-mercury theory. Essentially the argument is as follows: In order to make “A” from “B and C”, “B and C” become corrupted as soon as they combine to make “A,” so “B and C” clearly cannot exist within “A.” [9]

Paul then rebuttals against this argument in two ways: theoretical examples and scientific experimentations. One example is how a smaller number can exist in a larger number. For example, the quantity “3” resides in the quantity “4”; 4 can be viewed as the combination of 3 and 1. A less abstract example is a live tree and a dead one. The difference between them is simply the essence of life or its vegetative soul. The dead tree still contains the substantial form of the wood, so clearly that form must have been there even when the tree was alive. Paul’s experimental approach is to decompose metals into other materials, then attempt to recombine those materials into the metal again. If the sulfur-mercury theory is correct, you can decompose metals into the four elements, but when attempting to recombine the elements, there is no reason for the elements to recombine into any one particular metal. Paul writes that he successfully recreated the same metal after a process of calcining, dissolving, subliming, and lastly reducing metals. Since he was able to recreate the same metal that he started with, he obviously did not break the metal down into the pure elements, but instead into some intermediate phases. [10]

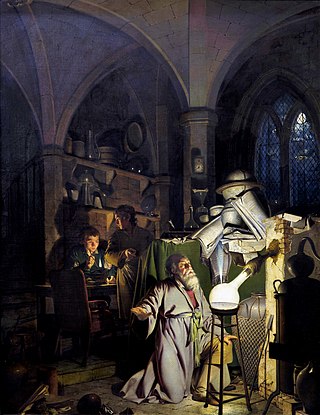

Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science under natural sciences that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, properties, behavior and the changes they undergo during a reaction with other substances. Chemistry also addresses the nature of chemical bonds in chemical compounds.

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula HNO3. It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitric acid has a concentration of 68% in water. When the solution contains more than 86% HNO3, it is referred to as fuming nitric acid. Depending on the amount of nitrogen dioxide present, fuming nitric acid is further characterized as red fuming nitric acid at concentrations above 86%, or white fuming nitric acid at concentrations above 95%.

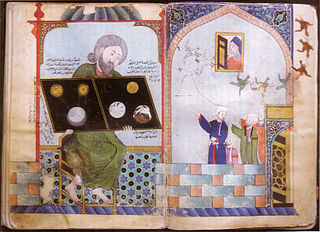

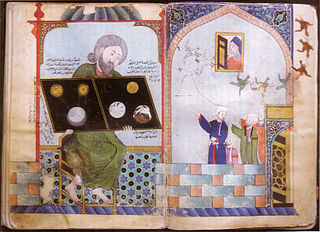

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, died c. 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The works that survive today mainly deal with alchemy and chemistry, magic, and Shi'ite religious philosophy. However, the original scope of the corpus was vast and diverse, covering a wide range of topics ranging from cosmology, astronomy and astrology, over medicine, pharmacology, zoology and botany, to metaphysics, logic, and grammar.

The philosopher's stone, or more properly philosophers' stone, is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver. It is also called the elixir of life, useful for rejuvenation and for achieving immortality; for many centuries, it was the most sought-after goal in alchemy. The philosopher's stone was the central symbol of the mystical terminology of alchemy, symbolizing perfection at its finest, enlightenment, and heavenly bliss. Efforts to discover the philosopher's stone were known as the Magnum Opus.

The compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula HCl and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colourless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hydrogen chloride gas and hydrochloric acid are important in technology and industry. Hydrochloric acid, the aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride, is also commonly given the formula HCl.

Vitriol is the general chemical name encompassing a class of chemical compound comprising sulfates of certain metals – originally, iron or copper. Those mineral substances were distinguished by their color, such as green vitriol for hydrated iron(II) sulfate and blue vitriol for hydrated copper(II) sulfate.

Alchemical symbols, originally devised as part of alchemy, were used to denote some elements and some compounds until the 18th century. Although notation was partly standardized, style and symbol varied between alchemists. Lüdy-Tenger published an inventory of 3,695 symbols and variants, and that was not exhaustive, omitting for example many of the symbols used by Isaac Newton. This page therefore lists only the most common symbols.

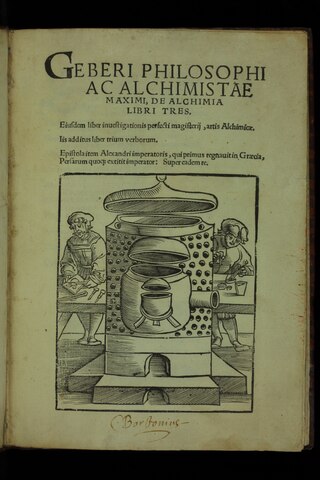

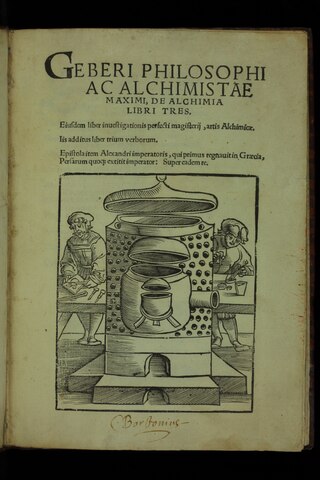

Pseudo-Geber is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan, an early alchemist of the Islamic Golden Age.

The history of chemistry represents a time span from ancient history to the present. By 1000 BC, civilizations used technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include the discovery of fire, extracting metals from ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, extracting chemicals from plants for medicine and perfume, rendering fat into soap, making glass, and making alloys like bronze.

Azoth is a fictitious universal medication or general strong solvent, sought for in alchemy. Similar to alkahest, another alchemical substance, the creation of Azoth was the aim of many alchemical works. Its symbol was the Caduceus. The term Azoth, while originally a term for an occult formula sought by alchemists much like the philosopher's stone, became a poetic word for the element mercury. The etymology of the name Azoth comes from Medieval Latin, an alteration of azoc, being originally derived from the Arabic al-zā'būq "the mercury".

The Aurora consurgens is an alchemical treatise of the 15th century famous for the rich illuminations that accompany it in some manuscripts. While in the last century, the text has been more commonly referred to as "Pseudo-Aquinas", there are as well arguments in favour of Thomas Aquinas, to whom it has originally been attributed in some manuscripts. The translated title from Latin into English is "Rising dawn."

Ceration is a chemical process, a common practice in alchemy. It is performed by continuously adding a liquid by imbibition to a hard, dry substance while it is heated. Typically, this treatment makes the substance softer, more like molten wax. Pseudo-Geber's Summa Perfectionis explains that ceration is "the mollification of an hard thing, not fusible unto liquefaction", and stresses the importance of correct humidity in the process.

Corpuscularianism is a set of theories that explain natural transformations as a result of the interaction of particles. It differs from atomism in that corpuscles are usually endowed with a property of their own and are further divisible, while atoms are neither. Although often associated with the emergence of early modern mechanical philosophy, and especially with the names of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, corpuscularian theories can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world refers to both traditional alchemy and early practical chemistry by Muslim scholars in the medieval Islamic world. The word alchemy was derived from the Arabic word كيمياء or kīmiyāʾ and may ultimately derive from the ancient Egyptian word kemi, meaning black.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to alchemy:

The origin and usage of the term metalloid is convoluted. Its origin lies in attempts, dating from antiquity, to describe metals and to distinguish between typical and less typical forms. It was first applied to metals that floated on water, and then more popularly to nonmetals. Only recently, since the mid-20th century, has it been widely used to refer to elements with intermediate or borderline properties between metals and nonmetals.

William R. Newman is Distinguished Professor and Ruth N. Halls Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University. Most of Newman’s work in the History of Science has been devoted to alchemy and "chymistry," the art-nature debate, and matter theories, particularly atomism. Newman is also General Editor of the Chymistry of Isaac Newton, an online resource combining born-digital editions of Newton’s alchemical writings with multimedia replications of Newton’s alchemical experiments. In addition, he was Director of the Catapult Center for Digital Humanities and Computational Analysis of Texts at Indiana University. Newman is on the editorial boards of Archimedes, Early Science and Medicine, and HOPOS.

The Mirror of Alchimy is a short alchemical manual, known in Latin as Speculum Alchemiae. Translated in 1597, it was only the second alchemical text printed in the English language. Long ascribed to Roger Bacon (1214-1294), the work is more likely the product of an anonymous author who wrote between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries.

De Alchemia is an early collection of alchemical writings first published by Johannes Petreius in Nuremberg in 1541. A second edition was published in Frankfurt in 1550 by the printer Cyriacus Jacobus.