Dantian is a concept in traditional Chinese medicine loosely translated as "elixir field", "sea of qi", or simply "energy center". Dantian are the "qi focus flow centers", important focal points for meditative and exercise techniques such as qigong, martial arts such as tai chi, and in traditional Chinese medicine.

The elixir of life, also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to cure all diseases. Alchemists in various ages and cultures sought the means of formulating the elixir.

The Three Treasures or Three Jewels are theoretical cornerstones in traditional Chinese medicine and practices such as neidan, qigong, and tai chi. They are also known as jing, qi, and shen.

Neidan, or internal alchemy, is an array of esoteric doctrines and physical, mental, and spiritual practices that Taoist initiates use to prolong life and create an immortal spiritual body that would survive after death. Also known as Jindan, inner alchemy combines theories derived from external alchemy, correlative cosmology, the emblems of the Yijing, and medical theory, with techniques of Taoist meditation, daoyin gymnastics, and sexual hygiene.

The Cantong qi is deemed to be the earliest book on alchemy in China. The title has been variously translated as Kinship of the Three, Akinness of the Three, Triplex Unity, The Seal of the Unity of the Three, and in several other ways. The full title of the text is Zhouyi cantong qi, which can be translated as, for example, The Kinship of the Three, in Accordance with the Book of Changes.

The Wuzhen pian is a 1075 Taoist classic on Neidan-style internal alchemy. Its author Zhang Boduan was a Song dynasty scholar of the Three teachings.

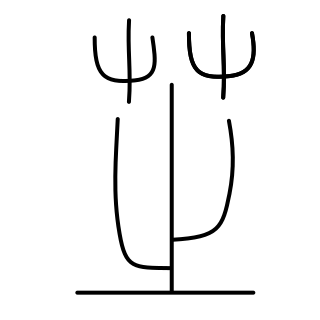

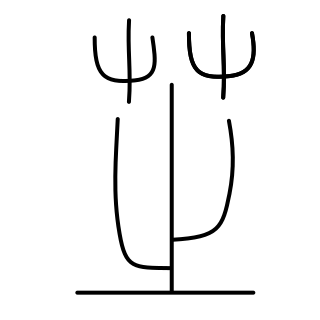

The Neijing Tu is a Daoist "inner landscape" diagram of the human body illustrating Neidan'internal alchemy', Wu Xing, Yin and Yang, and Chinese mythology.

Fangshi were Chinese technical specialists who flourished from the third century BCE to the fifth century CE. English translations of fangshi include alchemist, astrologer, diviner, exorcist, geomancer, doctor, magician, monk, mystic, necromancer, occultist, omenologist, physician, physiognomist, technician, technologist, thaumaturge, and wizard.

Baopuzi is a literary work written by Ge Hong, , a scholar during the turbulent Jin dynasty.

Waidan, translated as 'external alchemy' or 'external elixir', is the early branch of Chinese alchemy that focuses upon compounding elixirs of immortality by heating minerals, metals, and other natural substances in a luted crucible. The later branch of esoteric neidan 'inner alchemy', which borrowed doctrines and vocabulary from exoteric waidan, is based on allegorically producing elixirs within the endocrine or hormonal system of the practitioner's body, through Daoist meditation, diet, and physiological practices. The practice of waidan external alchemy originated in the early Han dynasty, grew in popularity until the Tang (618–907), when neidan began and several emperors died from alchemical elixir poisoning, and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

The Pill of Immortality, also known as xiandan (仙丹), jindan (金丹) or dan (丹) in general, was an elixir or pill sought by Chinese alchemists to confer physical or spiritual immortality. It is typically represented as a spherical pill of dark color and uniform texture, made of refined medical material. Colloquially and in Chinese medicine, the term can also refer to medicine of great efficacy.

Fabrizio Pregadio is a Sinologist and a translator of Chinese language texts into English related to Taoism and Neidan. He is currently affiliated with the International Consortium for Research in the Humanities, and is working on a project on the Taoist Master Liu Yiming (1734-1821) with the support of the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Liu Haichan was a Daoist xian who was a patriarch of the Quanzhen School, and a master of neidan "internal alchemy" techniques. Liu Haichan is associated with other Daoist transcendents, especially Zhongli Quan and Lü Dongbin, two of the Eight Immortals. Traditional Chinese and Japanese art frequently represents Liu with a string of square-holed cash coins and a mythical three-legged chanchu. In the present day, it is called the Jin Chan (金蟾), literally meaning "Money Toad", and Liu Haichan is considered an embodiment of Caishen, the God of Wealth.

Tao Hongjing (456–536), courtesy name Tongming, was a Chinese alchemist, astronomer, calligrapher, military general, musician, physician, and pharmacologist during the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589). A polymathic individual of many talents, he was best known as a founder of the Shangqing "Highest Clarity" School of Taoism and the compiler-editor of the basic Shangqing scriptures.

In Chinese alchemy, elixir poisoning refers to the toxic effects from elixirs of immortality that contained metals and minerals such as mercury and arsenic. The official Twenty-Four Histories record numerous Chinese emperors, nobles, and officials who died from taking elixirs to prolong their lifespans. The first emperor to die from elixir poisoning was likely Qin Shi Huang and the last was the Yongzheng Emperor. Despite common knowledge that immortality potions could be deadly, fangshi and Daoist alchemists continued the elixir-making practice for two millennia.

Langgan is the ancient Chinese name of a gemstone which remains an enigma in the history of mineralogy; it has been identified, variously, as blue-green malachite, blue coral, white coral, whitish chalcedony, red spinel, and red jade. It is also the name of a mythological langgan tree of immortality found in the western paradise of Kunlun Mountain, and the name of the classic waidan alchemical elixir of immortality langgan huadan 琅玕華丹 "Elixir Efflorescence of Langgan".

Li Shaojun was a fangshi, reputed xian, retainer of Emperor Wu of Han, and the earliest known Chinese alchemist. In the early history of Chinese waidan, Li is the only fangshi whose role is documented by both historical and alchemical (Baopuzi) sources.

The Chinese term zhī (芝) commonly means "fungi; mushroom", best exemplified by the medicinal Lingzhi mushroom, but in Daoism it referred to a class of supernatural plant, animal, and mineral substances that were said to confer instantaneous xian immortality when ingested. In the absence of a semantically better English word, scholars have translated the wide-ranging meaning of zhi as "excrescences", "exudations", and "cryptogams".

Yin Changsheng was a famous Daoist xian from Xinye who lived during the Eastern Han dynasty. After serving more than ten years as a disciple of the transcendent Maming Sheng he received the secret Taiqing scriptures on Waidan. Several extant texts are ascribed to Yin Changsheng, such as the Jinbi wu xianglei can tong qi.

Shengtai is a Chinese syncretic metaphor for achieving Buddhist liberation or Daoist transcendence. The circa fifth century CE Chinese Buddhist Humane King Sutra first recorded shengtai describing the bodhisattva path towards attaining Buddhahood; shengtai was related with the more familiar Indian Mahayana concept of tathāgatagarbha ("embryo/womb of the Buddha", Chinese rulaizang that all sentient beings are born with the Buddha-nature potential to become enlightened. The Chan Buddhist teaching master Mazu Daoyi first mentioned post-enlightenment zhangyang shengtai, and by the tenth century Chan monks were regularly described as recluses nurturing their sacred embryo in isolated locations. The renowned Daoist Zhang Boduan was first to use the expression shengtai in a context of physiological neidan Internal Alchemy, and neidan adepts developed prolonged meditation techniques through which one can supposedly become pregnant, gestate, and give birth to a spiritually perfected doppelganger.