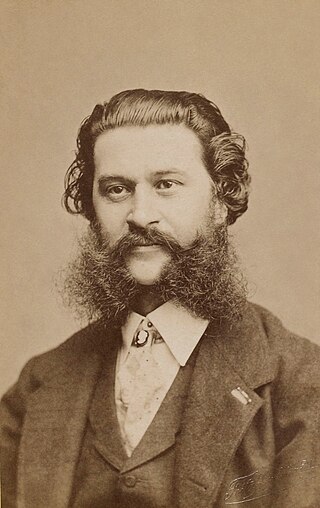

The Gypsy Baron is an operetta in three acts by Johann Strauss II which premiered at the Theater an der Wien on 24 October 1885. Its German libretto by Ignaz Schnitzer is based on the unpublished 1883 story Saffi by Mór Jókai. Jokai later published a novel A cigánybáró in 1885 using an expanded version of this same story.

Ferenc Farkas was a Hungarian composer.

Hungary has had a notable cinema industry since the beginning of the 20th century, including Hungarians who affected the world of motion pictures both within and beyond the country's borders. The former could be characterized by directors István Szabó, Béla Tarr, or Miklós Jancsó; the latter by William Fox and Adolph Zukor, the founders of Fox Studios and Paramount Pictures respectively, or Alexander Korda, who played a leading role in the early period of British cinema. Examples of successful Hungarian films include Merry-go-round, Mephisto, Werckmeister Harmonies and Kontroll.

The Man with the Golden Touch is an 1872 novel by Hungarian novelist Mór Jókai. As Jókai states in the afterword of the novel, it was based on a true story he had heard from his grand-aunt as a child.

Zoltán Latinovits was a Hungarian actor.

Zoltán Huszárik was an influential Hungarian film director, screenwriter, visual artist and occasional actor, an acclaimed auteur of the European modern art film.

Big Read is the Hungarian version of the BBC Big Read.

Tibor Molnár was a Hungarian film actor. He appeared in more than 90 films between 1948 and 1982.

Judit Elek is a Hungarian film director and screenwriter. She directed 16 films between 1962 and 2006. Her film Mária-nap was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival.

Szaffi is a 1985 Hungarian-Canadian animated film directed by Attila Dargay. It is based on the 1885 book The Gypsy Baron by Mór Jókai, about the romance between a poor Hungarian aristocrat and a mysterious Romani-looking Turkish girl in the 18th century. Music from Johann Strauss II's operetta The Gypsy Baron, based on the same novel, is used for the film's soundtrack.

Robert Nisbet Bain (1854–1909) was a British historian and linguist who worked for the British Museum.

The Man of Gold is a 1962 Hungarian historical film directed by Viktor Gertler and starring András Csorba, Ilona Béres and Ernő Szabó. It was based on the novel The Man with the Golden Touch by Mór Jókai, which has been adapted for the screen several times.

Zoltán Greguss was a Hungarian film actor.

Tibor Bitskey was a Hungarian television and film actor.

Tamás Major was a Hungarian stage and film actor. He also acted as the director of the Hungarian National Theatre from 1945 to 1962.

Jókai bean soup is a Hungarian bean soup. It is a rich bean soup with many vegetables, smoked pork hock pieces and noodles. It is often made to be spicy or some sort of hot chili offered with it. Despite its richness it is served with sour cream on top and white bread, and this soup is a lunch or dinner in itself.

Béla Ferenc József Grünwald de Bártfa was a Hungarian nationalist politician and historian who was active in Upper Hungary.

Zoltán Kárpáthy is a 1966 Hungarian drama film directed by Zoltán Várkonyi and based on the novel with the same name by Mór Jókai.

József Sas was a Hungarian actor, comedian and theatre manager. He was director of the Mikroszkóp Theatre from 1985 to 2009.

Miklós Hajdufy was a Hungarian screenwriter and director.

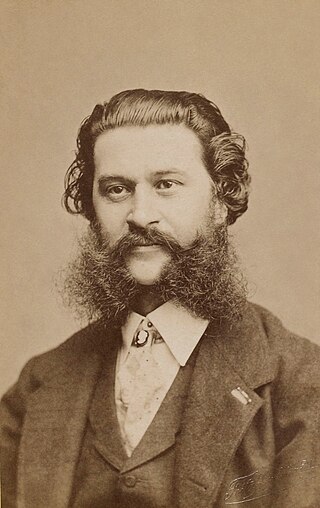

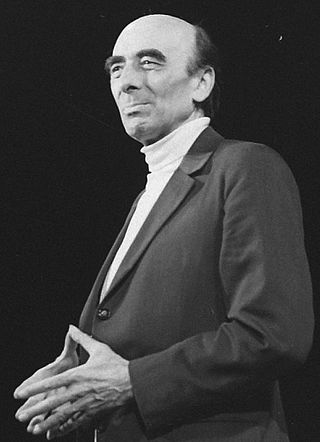

![Jokai in his study;

photograph by Mor Erdelyi [hu] Mor Erdelyi - Jokai in his study - Google Art Project.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/M%C3%B3r_Erd%C3%A9lyi_-_J%C3%B3kai_in_his_study_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/250px-M%C3%B3r_Erd%C3%A9lyi_-_J%C3%B3kai_in_his_study_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)