Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the Iberian Peninsula. The term, which is derived from the Hebrew Sepharad, can also refer to the Jews of the Middle East and North Africa, who were also heavily influenced by Sephardic law and customs. Many Iberian Jewish exiled families also later sought refuge in those Jewish communities, resulting in ethnic and cultural integration with those communities over the span of many centuries. The majority of Sephardim live in Israel.

Sephardic law and customs are the law and customs of Judaism which are practiced by Sephardim or Sephardic Jews ; the descendants of the historic Jewish community of the Iberian Peninsula, what is now Spain and Portugal. Many definitions of "Sephardic" also include Mizrahi Jews, most of whom follow the same traditions of worship as those which are followed by Sephardic Jews. The Sephardi Rite is not a denomination nor is it a movement like Orthodox Judaism, Reform Judaism, and other Ashkenazi Rite worship traditions. Thus, Sephardim comprise a community with distinct cultural, juridical and philosophical traditions.

Sephardic music is an umbrella term used to refer to the music of the Sephardic Jewish community. Sephardic Jews have a diverse repertoire the origins of which center primarily around the Mediterranean basin. In the secular tradition, material is usually sung in dialects of Judeo-Spanish, though other languages including Hebrew, Turkish, Greek, and other local languages of the Sephardic diaspora are widely used. Sephardim maintain geographically unique liturgical and para-liturgical traditions.

Maghrebi Jews, are a Jewish diaspora group with a long history in the Maghreb region of North Africa, which includes present-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. These communities were established long before the Arab conquest, and continued to develop under Muslim rule during the Middle Ages. Maghrebi Jews represent the second-largest Jewish diaspora group, with their descendants forming a major part of the global Jewish population.

Mizrahi Jews, also known as Mizrahim (מִזְרָחִים) in plural and Mizrahi (מִזְרָחִי) in singular, and alternatively referred to as Oriental Jews or Edot HaMizrach, are terms used in Israeli discourse to refer to a grouping of Jewish communities that lived in the Muslim world. Mizrahi is a political sociological term that was coined with the creation of the State of Israel. It translates as "Easterner" in Hebrew.

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ad-Dārija to differentiate it from Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, Hassaniya and Saharan Arabic dialects. Maghrebi Arabic has a predominantly Semitic and Arabic vocabulary, although it contains a significant number of Berber loanwords, which represent 2–3% of the vocabulary of Libyan Arabic, 8–9% of Algerian and Tunisian Arabic, and 10–15% of Moroccan Arabic. Maghrebi Arabic was formerly spoken in Al-Andalus and Sicily until the 17th and 13th centuries, respectively, in the extinct forms of Andalusi Arabic and Siculo-Arabic. The Maltese language is believed to have its source in a language spoken in Muslim Sicily that ultimately originates from Tunisia, as it contains some typical Maghrebi Arabic areal characteristics.

A tagine or tajine, also tajin or tagin is a Maghrebi dish, and also the earthenware pot in which it is cooked. It is also called maraq or marqa.

Jewish ethnic divisions refer to many distinctive communities within the world's Jewish population. Although "Jewish" is considered an ethnicity itself, there are distinct ethnic subdivisions among Jews, most of which are primarily the result of geographic branching from an originating Israelite population, mixing with local communities, and subsequent independent evolutions.

Judaeo-Romance languages are Jewish languages derived from Romance languages, spoken by various Jewish communities originating in regions where Romance languages predominate, and altered to such an extent to gain recognition as languages in their own right. The status of many Judaeo-Romance languages is controversial as, despite manuscripts preserving transcriptions of Romance languages using the Hebrew alphabet, there is often little-to-no evidence that these "dialects" were actually spoken by Jews living in the various European nations.

Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also called Western Sephardim, Iberian Jews, or Peninsular Jews, are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews who are largely descended from Jews who lived as New Christians in the Iberian Peninsula during the few centuries following the forced expulsion of unconverted Jews from Spain in 1492 and from Portugal in 1497. They should therefore be distinguished both from the descendants of those expelled in 1492 and from the present-day Jewish communities of Spain and Portugal.

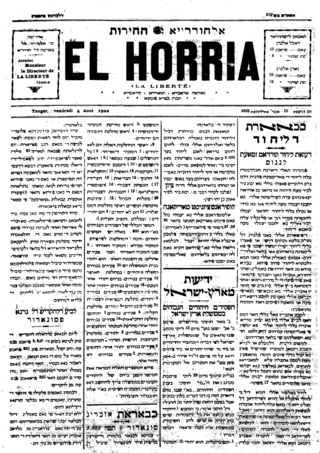

Judeo-Moroccan Arabic is the variety or the varieties of the Moroccan vernacular Arabic spoken by Moroccan Jews living or formerly living in Morocco. Historically, the majority of Moroccan Jews spoke Moroccan vernacular Arabic, or Darija, as their first language, even in Amazigh areas, which was facilitated by their literacy in Hebrew script. The Darija spoken by Moroccan Jews, which they referred to as al-‘arabiya diyalna as opposed to ‘arabiya diyal l-məslimīn, typically had distinct features, such as š>s and ž>z "lisping," some lexical borrowings from Hebrew, and in some regions Hispanic features from the migration of Sephardi Jews following the Alhambra Decree. The Jewish dialects of Darija spoken in different parts of Morocco had more in common with the local Moroccan Arabic dialects than they did with each other.

Sephardic Jewish cuisine, belonging to the Sephardic Jews—descendants of the Jewish population of the Iberian Peninsula until their expulsion in 1492—encompassing traditional dishes developed as they resettled in the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and the Mediterranean, including Jewish communities in Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, and Syria, as well as the Sephardic community in the Land of Israel. It may also refer to the culinary traditions of the Western Sephardim, who settled in Holland, England, and from these places elsewhere. The cuisine of Jerusalem, in particular, is considered predominantly Sephardic.

Musta'arabi Jews were the Arabic-speaking Jews, largely Mizrahi Jews and Maghrebi Jews, who lived in the Middle East and North Africa prior to the arrival and integration of Ladino-speaking Sephardi Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, following their expulsion from Spain in 1492. Following their expulsion, Sephardi Jewish exiles moved into the Middle East and North Africa, and settled among the Musta'arabi.

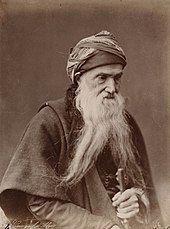

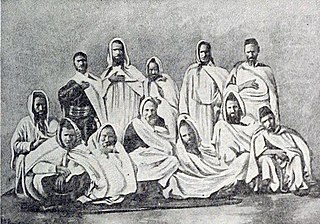

Moroccan Jews are Jews who live in or are from Morocco. Moroccan Jews constitute an ancient community dating to Roman times. Jews began immigrating to the region as early as 70 CE. They were later met by a second wave of migrants from the Iberian Peninsula in the period which immediately preceded and followed the issuing of the 1492 Alhambra Decree, when Jews were expelled from Spain, and soon afterward, from Portugal. This second wave of immigrants changed Moroccan Jewry, which largely embraced the Andalusian Sephardic liturgy, to switch to a mostly Sephardic identity.

North African Americans are Americans with origins in the region of North Africa. This group includes Americans of Algerian, Egyptian, Libyan, Moroccan, and Tunisian descent.

Sephardic Bnei Anusim is a modern term which is used to define the contemporary Christian descendants of an estimated quarter of a million 15th-century Sephardic Jews who were coerced or forced to convert to Catholicism during the 14th and 15th centuries in Spain and Portugal. The vast majority of conversos remained in Spain and Portugal, and their descendants, who number in the millions, live in both of these countries. The small minority of conversos who emigrated normally chose to emigrate to destinations where Sephardic communities already existed, particularly to the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, but some of them emigrated to more tolerant cities in Europe, where many of them immediately reverted to Judaism. In theory, very few of them would have traveled to Latin America with colonial expeditions, because only those Spaniards who could certify that they had no recent Muslim or Jewish ancestry were supposed to be allowed to travel to the New World. Recent genetic studies suggest that the arrival of the Sephardic ancestors of Latin American populations coincided with the initial colonization of Latin America, which suggests that significant numbers of recent converts were able to travel to the new world and contribute to the gene pool of modern Latin American populations despite an official prohibition on them doing so. In addition, later arriving Spanish immigrants would have themselves contributed additional converso ancestry in some parts of Latin America.

Eastern Sephardim are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews mostly descended from Jewish families which were exiled from Iberia in the 15th century, following the Alhambra Decree of 1492 in Spain and a similar decree in Portugal five years later. This branch of descendants of Iberian Jews settled across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Megorashim or rūmiyīn is a term used to refer to Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who arrived in North Africa as a result of the anti-Jewish persecutions of 1391 and the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. These migrants were distinct from pre-existing North African Jews called Toshavim. The Toshavim had been present in North Africa since ancient times, spoke the local languages, and had traditions that were influenced by Maghrebi Islam. The Megorashim influenced North African Judaism, incorporating traditions from Spain. They eventually merged with the Toshavim, so that it is now difficult to distinguish between the two groups. The Jews of North Africa are often referred to as Sephardi, a term that emphasizes their Iberian traditions.

Toshavim or bildiyīn is a generic reference to non-Sephardic Jews who inhabited lands in which the Jews expelled from Spain in 15th century settled. The Jews in the area of North Africa known as Maghreb are also referred to as Maghrebim. In particular, the term "Toshavim" was applied to the Jews of Morocco. Both groups are considered indigenous to the area despite their migration and diaspora origins.