The lands of Belarus during the Middle Ages became part of Kievan Rus' and were split between different regional principalities, including Polotsk, Turov, Vitebsk, and others. Following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, these lands were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which later was merged into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th century.

Seventeen days after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet Union entered the eastern regions of Poland and annexed territories totalling 201,015 square kilometres (77,612 sq mi) with a population of 13,299,000. Inhabitants besides ethnic Poles included Belarusian and Ukrainian major population groups, and also Czechs, Lithuanians, Jews, and other minority groups.

The Polish minority in the Soviet Union are Polish diaspora who used to reside near or within the borders of the Soviet Union before its dissolution. Some of them continued to live in the post-Soviet states, most notably in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, the areas historically associated with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan among others.

The Treaty of Riga was signed in Riga, Latvia, on 18 March 1921 between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine on the other, ending the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921). The chief negotiators of the peace were Jan Dąbski for the Polish side and Adolph Joffe for the Soviet side.

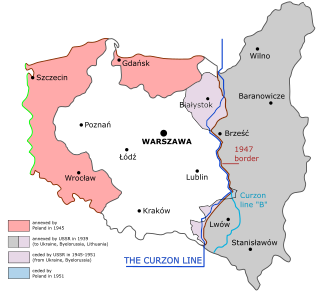

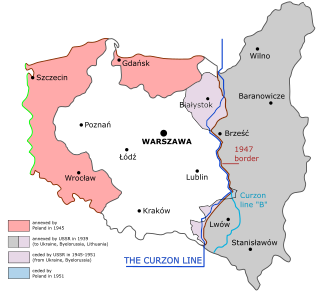

Eastern Borderlands or simply Borderlands was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with a Polish minority, it amounted to nearly half of the territory of interwar Poland. Historically situated in the eastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the 18th-century foreign partitions it was divided between the Empires of Russia and Austria-Hungary, and ceded to Poland in 1921 after the Treaty of Riga. As a result of the post-World War II border changes, all of the territory was ceded to the USSR, and none of it is in modern Poland.

Polish National Districts were national districts of the Soviet Union in the interbellum period providing national autonomy for Polish minorities in the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republics of the USSR. They were created in an attempt to live up to the postulate of Leninism about the rights of nations for self-determination. Also, creation of these regions served one of purposes of the Bolsheviks to export the revolution since after their defeat in the Polish-Soviet War, the Soviets did not give up their idea of creating a Soviet Republic in Poland. Polish National Districts were supposed to be the origin of future Soviet Poland. They both were disbanded in mid-1930s and a significant part of their populations was deported to Kazakhstan during the Great Purge.

The Polish diaspora comprises Poles and people of Polish heritage or origin who live outside Poland. The Polish diaspora is also known in modern Polish as Polonia, the name for Poland in Latin and many Romance languages.

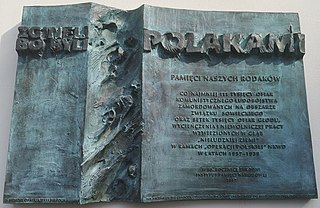

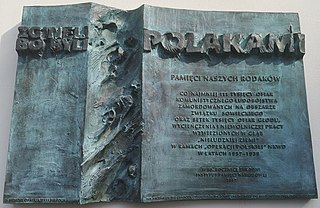

The Polish Operation of the NKVD in 1937–1938 was an anti-Polish mass-ethnic cleansing operation of the NKVD carried out in the Soviet Union against Poles during the period of the Great Purge. It was ordered by the Politburo of the Communist Party against so-called "Polish spies" and customarily interpreted by NKVD officials as relating to 'absolutely all Poles'. It resulted in the sentencing of 139,835 people, and summary executions of 111,091 Poles living in or near the Soviet Union. The operation was implemented according to NKVD Order No. 00485 signed by Nikolai Yezhov.

The Soviet NKVD Order No. 00485 was an anti-Polish ethnic cleansing campaign issued on August 11, 1937, which laid the foundation for the systematic elimination of the Polish minority in the Soviet Union between 1937 and 1938. The order was called "On the liquidation of Polish sabotage and espionage groups and units of the POW". It is dated August 9, 1937, was issued by the Central Committee Politburo, and signed by Nikolai Yezhov, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs. The operation was at the center of the national operations of the NKVD, and the largest ethnically motivated shooting action of the Great Terror.

The Union of Poles in Belarus is an organisation located in Belarus. The group, which has a membership of 20,000 people, represents the Polish minority in Belarus, numbering about 300,000 it forms the second largest ethnic minority in the country after the Russians, at 3.1% of the total population. An estimated 180,905 Belarusian Poles live in large agglomerations and 113,644 in smaller settlements, with the number of women exceeding the number of men by about 33,000., as per official data.

Western Belorussia or Western Belarus is a historical region of modern-day Belarus which belonged to the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period. For twenty years before the 1939 invasion of Poland, it was the northern part of the Polish Kresy macroregion. Following the end of World War II in Europe, most of Western Belorussia was ceded to the Soviet Union by the Allies, while some of it, including Białystok, was given to the Polish People's Republic. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Western Belorussia formed the western part of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR). Today, it constitutes the west of modern Belarus.

The Poles of Lithuania, also called Lithuanian Poles, estimated at 183,000 people in the Lithuanian census of 2021 or 6.5% of Lithuania's total population, are the country's largest ethnic minority.

The Lithuanian minority in Poland consists of 8,000 people living chiefly in the Podlaskie Voivodeship, in the north-eastern part of Poland. The Lithuanian embassy in Poland notes that there are about 15,000 people in Poland of Lithuanian ancestry.

The Belarusian minority in Poland is composed of 47,000 people according to the Polish census of 2011. This number decreased in the last decades from over 300,000 due to an active process of assimilation. Most of them live in the Podlaskie Voivodeship.

Union of Poles in Lithuania is an organization formed in 1989 to bring together members of Polish minority in Lithuania. It numbers between 6,000 to 11,000 members. It defends the civil rights of the Polish minority and engages in educational, cultural and economic activities. It is the largest Polish organization in Lithuania, and was created in 1990.

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar Poland, were the forced migrations of Poles toward the end and in the aftermath of World War II. These were the result of a Soviet Union policy that had been ratified by the main Allies of World War II. Similarly, the Soviet Union had enforced policies between 1939 and 1941 which targeted and expelled ethnic Poles residing in the Soviet zone of occupation following the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland. The second wave of expulsions resulted from the retaking of Poland from the Wehrmacht by the Red Army. The USSR took over territory for its western republics.

The Republic of Poland and the Republic of Belarus established diplomatic relations on 2 March 1992. Poland was one of the first countries to recognise Belarusian independence. Both countries share a border and have shared histories, for they have been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and later, the Russian Empire. They joined the United Nations together in October 1945 as original members. The two countries are currently engaged in a border crisis.

Historically, Białystok has been a destination for internal and foreign immigration, especially from Central and Eastern Europe. In addition to the Polish minority in 19th century, there was a significant Jewish majority in Białystok. According to Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 66,000, Jews constituted 41,900. In 1936, Białystok had a population of 99,722, of whom: 50.9% (50,758) were Poles, 42.6% (42,482) Jews, 2.1% (2,094) Germans and 0.4% (359) Russians. World War II changed all of this, in 1939, ca. 107,000 persons lived in Białystok, but in 1946 – only 56,759, and to this day there is much less ethnic diversity than in the previous 300 years of the city's history. Currently the city's population is 97% Polish, 2.5% Belarusian and 0.5% of a number of minorities including Russians, Lipka Tartars, Ukrainians and Romani. Most of the modern day population growth is based on internal migration and urbanization.

Tomasz Krzysztof Sommer is a Polish writer, journalist and publisher, editor-in-chief of weekly magazine Najwyższy Czas!. Sommer graduated from the University of Warsaw Department of Journalism and Political Science, and received his Ph.D. in sociology at the School of Social Sciences of the Polish Academy of Sciences Institute of Philosophy and Sociology.

Soviet leaders and authorities officially condemned nationalism and proclaimed internationalism, including the right of nations and peoples to self-determination. Soviet internationalism during the era of the USSR and within its borders meant diversity or multiculturalism. This is because the USSR used the term "nation" to refer to ethnic or national communities and or ethnic groups. The Soviet Union claimed to be supportive of self-determination and rights of many minorities and colonized peoples. However, it significantly marginalized people of certain ethnic groups designated as "enemies of the people", pushed their assimilation, and promoted chauvinistic Russian nationalistic and settler-colonialist activities in their lands. Whereas Vladimir Lenin had supported and implemented policies of korenizatsiia, Joseph Stalin reversed much of the previous policies, signing off on orders to deport and exile multiple ethnic-linguistic groups brandished as "traitors to the Fatherland", including the Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Kalmyks, Koreans and Meskhetian Turks, with those, who survived the collective deportation to Siberia or Central Asia, were legally designated "special settlers", meaning that they were officially second-class citizens with few rights and were confined within small perimeters.