| Polistes pacificus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Vespidae |

| Subfamily: | Polistinae |

| Tribe: | Polistini |

| Genus: | Polistes |

| Species: | P. pacificus |

| Binomial name | |

| Polistes pacificus (Fabricius, 1804) | |

| Synonyms [1] | |

| |

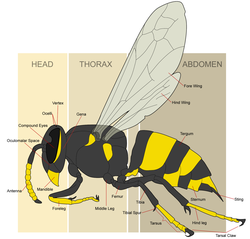

Polistes pacificus is a Neotropical species of social paper wasp belonging to the subfamily Polistinae and the family Vespidae. [2] P. pacificus can be found distributed throughout most of Central and South America and parts of southern North America. First discovered by Johan Christian Fabricius in 1804, P. pacificus is much darker in color than some other more recognizable Polistes wasps, and is one of the insects commonly eaten by several indigenous groups in Venezuela and Colombia. [3] [4]

Contents

- Taxonomy and phylogenetics

- Phylogenetic tree

- Synonyms

- Description and identification

- Distinguishing P. pacificus from similar species

- The defined morphological criteria

- Nest identification

- Distribution and habitat

- Geographic distribution

- Nest-building habitats

- Colony cycle

- Interactions with other species

- Diet

- Predators

- Defense

- Communication

- Lack of visual signaling

- Worker mouthing and rubbing

- Human importance

- Agriculture

- Human food source

- Cultural significance of wasp stings

- References