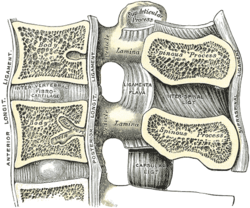

An intervertebral disc lies between adjacent vertebrae in the vertebral column. Each disc forms a fibrocartilaginous joint, to allow slight movement of the vertebrae, to act as a ligament to hold the vertebrae together, and to function as a shock absorber for the spine.

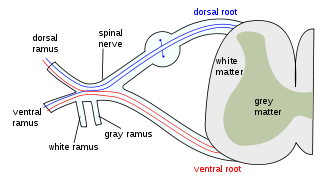

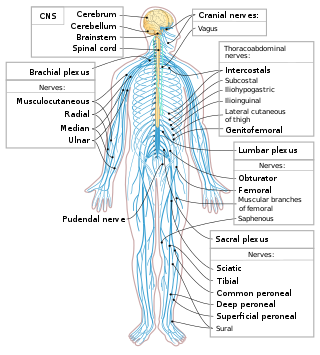

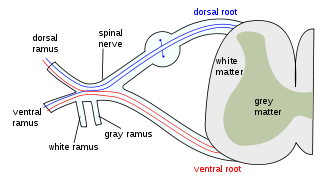

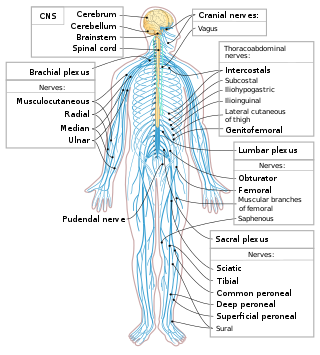

A spinal nerve is a mixed nerve, which carries motor, sensory, and autonomic signals between the spinal cord and the body. In the human body there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves, one on each side of the vertebral column. These are grouped into the corresponding cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral and coccygeal regions of the spine. There are eight pairs of cervical nerves, twelve pairs of thoracic nerves, five pairs of lumbar nerves, five pairs of sacral nerves, and one pair of coccygeal nerves. The spinal nerves are part of the peripheral nervous system.

The lumbar vertebrae are, in human anatomy, the five vertebrae between the rib cage and the pelvis. They are the largest segments of the vertebral column and are characterized by the absence of the foramen transversarium within the transverse process and by the absence of facets on the sides of the body. They are designated L1 to L5, starting at the top. The lumbar vertebrae help support the weight of the body, and permit movement.

The thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm, is a sheet of internal skeletal muscle in humans and other mammals that extends across the bottom of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm is the most important muscle of respiration, and separates the thoracic cavity, containing the heart and lungs, from the abdominal cavity: as the diaphragm contracts, the volume of the thoracic cavity increases, creating a negative pressure there, which draws air into the lungs. Its high oxygen consumption is noted by the many mitochondria and capillaries present; more than in any other skeletal muscle.

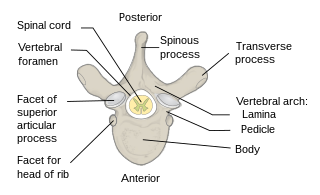

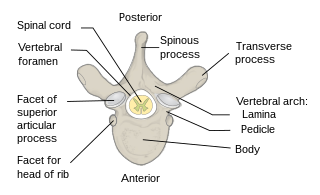

In human anatomy, the spinal canal is the canal that contains the spinal cord within the vertebral column. It is a process of the dorsal body cavity. The spinal canal is enclosed within the foramina of the vertebrae. In the intervertebral spaces, the canal is protected by the ligamentum flavum posteriorly and the posterior longitudinal ligament anteriorly.

Spondylosis is the degeneration of the vertebral column from any cause. In the more narrow sense it refers to spinal osteoarthritis, the age-related degeneration of the spinal column, which is the most common cause of spondylosis. The degenerative process in osteoarthritis chiefly affects the vertebral bodies, the neural foramina and the facet joints. If severe, it may cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots with subsequent sensory or motor disturbances, such as pain, paresthesia, imbalance, and muscle weakness in the limbs.

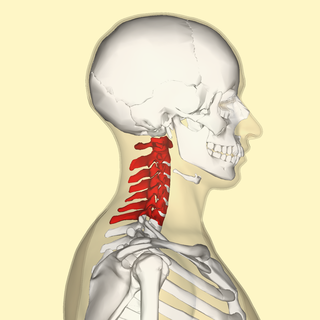

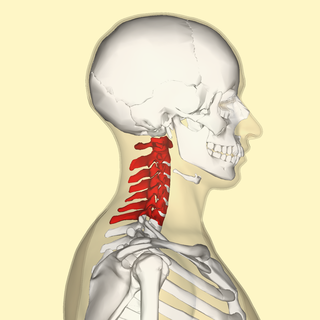

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae lie caudal of cervical vertebrae. In sauropsid species, the cervical vertebrae bear cervical ribs. In lizards and saurischian dinosaurs, the cervical ribs are large; in birds, they are small and completely fused to the vertebrae. The vertebral transverse processes of mammals are homologous to the cervical ribs of other amniotes. Most mammals have seven cervical vertebrae, with the only three known exceptions being the manatee with six, the two-toed sloth with five or six, and the three-toed sloth with nine.

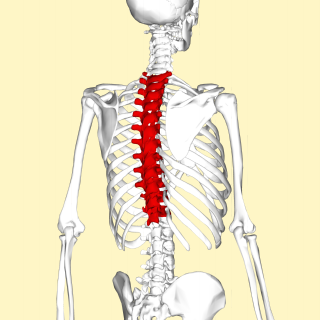

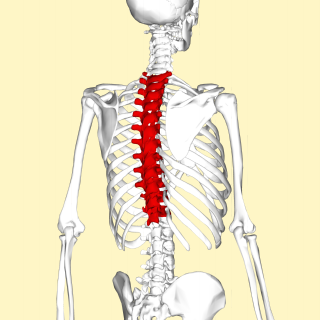

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae and they are intermediate in size between the cervical and lumbar vertebrae; they increase in size going towards the lumbar vertebrae, with the lower ones being much larger than the upper. They are distinguished by the presence of facets on the sides of the bodies for articulation with the heads of the ribs, as well as facets on the transverse processes of all, except the eleventh and twelfth, for articulation with the tubercles of the ribs. By convention, the human thoracic vertebrae are numbered T1–T12, with the first one (T1) located closest to the skull and the others going down the spine toward the lumbar region.

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a medical condition typically brought on by the normal aging process in which there are anatomic changes and possibly a loss of function of one or more intervertebral discs of the spine. DDD can take place with or without symptoms, but is typically identified once symptoms arise. The root cause is thought to be loss of soluble proteins within the fluid contained in the disc with resultant reduction of the oncotic pressure, which in turn causes loss of fluid volume. Normal downward forces cause the affected disc to lose height, and the distance between vertebrae is reduced. The anulus fibrosus, the tough outer layers of a disc, also weakens. This loss of height causes laxity of the longitudinal ligaments, which may allow anterior, posterior, or lateral shifting of the vertebral bodies, causing facet joint malalignment and arthritis; scoliosis; cervical hyperlordosis; thoracic hyperkyphosis; lumbar hyperlordosis; narrowing of the space available for the spinal tract within the vertebra ; or narrowing of the space through which a spinal nerve exits with resultant inflammation and impingement of a spinal nerve, causing a radiculopathy.

The anterior longitudinal ligament is a ligament that extends across the anterior/ventral aspect of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs the spine.

The supraspinous ligament, also known as the supraspinal ligament, is a ligament found along the vertebral column.

The ligamenta flava are a series of ligaments that connect the ventral parts of the laminae of adjacent vertebrae. They help to preserve upright posture, preventing hyperflexion, and ensuring that the vertebral column straightens after flexion. Hypertrophy can cause spinal stenosis.

The intervertebral foramen is a foramen between two spinal vertebrae. Cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae all have intervertebral foramina.

A spinal disc herniation is an injury to the cushioning and connective tissue between vertebrae, usually caused by excessive strain or trauma to the spine. It may result in back pain, pain or sensation in different parts of the body, and physical disability. The most conclusive diagnostic tool for disc herniation is MRI, and treatment may range from painkillers to surgery. Protection from disc herniation is best provided by core strength and an awareness of body mechanics including posture.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to human anatomy:

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the spinal cord, which contains cerebrospinal fluid. The brain and spinal cord together make up the central nervous system (CNS). In humans, the spinal cord begins at the occipital bone, passing through the foramen magnum and then enters the spinal canal at the beginning of the cervical vertebrae. The spinal cord extends down to between the first and second lumbar vertebrae, where it ends. The enclosing bony vertebral column protects the relatively shorter spinal cord. It is around 45 cm (18 in) long in adult men and around 43 cm (17 in) long in adult women. The diameter of the spinal cord ranges from 13 mm in the cervical and lumbar regions to 6.4 mm in the thoracic area.

Denticulate ligaments are lateral projections of the spinal pia mater forming triangular-shaped ligaments that anchor the spinal cord along its length to the dura mater on each side. There are usually 21 denticulate ligaments on each side, with the uppermost pair occurring just below the foramen magnum, and the lowest pair occurring between spinal nerve roots of T12 and L1. The denticulate ligaments are traditionally believed to provide stability for the spinal cord against motion within the vertebral column.

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord found in all chordates has been replaced by a segmented series of bone: vertebrae separated by intervertebral discs. Individual vertebrae are named according to their region and position, and can be used as anatomical landmarks in order to guide procedures such as lumbar punctures. The vertebral column houses the spinal canal, a cavity that encloses and protects the spinal cord.

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae, each constituting a characteristic irregular bone whose complex structure is composed primarily of bone, and secondarily of hyaline cartilage. They show variation in the proportion contributed by these two tissue types; such variations correlate on one hand with the cerebral/caudal rank, and on the other with phylogenetic differences among the vertebrate taxa.