Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

The philosopher's stone or more properly philosophers' stone, is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver. It is also called the elixir of life, useful for rejuvenation and for achieving immortality; for many centuries, it was the most sought goal in alchemy. The philosopher's stone was the central symbol of the mystical terminology of alchemy, symbolizing perfection at its finest, enlightenment, and heavenly bliss. Efforts to discover the philosopher's stone were known as the Magnum Opus.

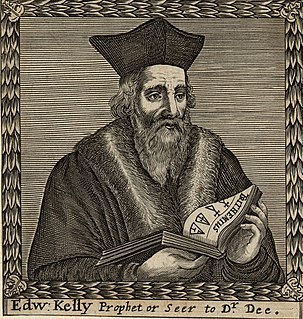

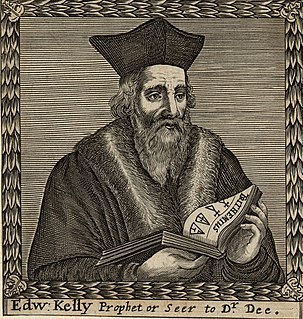

Sir Edward Kelley or Kelly, also known as Edward Talbot, was an English Renaissance occultist and scryer. He is best known for working with John Dee in his magical investigations. Besides the professed ability to see spirits or angels in a "shew-stone" or mirror, which John Dee so valued, Kelley also claimed to possess the secret of transmuting base metals into gold, the goal of alchemy, as well as the supposed philosopher's stone itself.

James Price (1752–1783) was an English chemist and alchemist who claimed to be able to turn mercury into silver or gold. When challenged to perform the conversion in front of credible witnesses for a second time, he instead committed suicide by drinking prussic acid.

Michael Sendivogius was a Polish alchemist, philosopher, and medical doctor. A pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemical compounds. He discovered that air is not a single substance and contains a life-giving substance—later called oxygen—170 years before Scheele's discovery of the element. He correctly identified this 'food of life' with the gas given off by heating nitre (saltpetre). This substance, the 'central nitre', had a central position in Sendivogius' schema of the universe.

"The Canon's Yeoman's Tale" is one of The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer.

Denis Zachaire (1510–1556) is the pseudonym of a 16th-century alchemist who spent his life and family fortune in a futile search for the Philosopher's Stone and the Elixir of Life.

The Alchemist is a comedy by English playwright Ben Jonson. First performed in 1610 by the King's Men, it is generally considered Jonson's best and most characteristic comedy; Samuel Taylor Coleridge believed that it had one of the three most perfect plots in literature. The play's clever fulfilment of the classical unities and vivid depiction of human folly have made it one of the few Renaissance plays with a continuing life on stage, apart from a period of neglect during the Victorian era.

George Starkey (1628–1665) was a Colonial American alchemist, medical practitioner, and writer of numerous commentaries and chemical treatises that were widely circulated in Western Europe and influenced prominent men of science, including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. After relocating from New England to London, England, in 1650, Starkey began writing under the pseudonym Eirenaeus Philalethes. Starkey remained in England and continued his career in medicine and alchemy until his death in the Great Plague of London in 1665.

Sir George Ripley was an English Augustinian canon, author, and alchemist.

Diana's Tree, also known as the Philosopher's Tree, was considered a precursor to the Philosopher’s Stone and resembled coral in regards to its structure. It is a dendritic amalgam of crystallized silver, obtained from mercury in a solution of silver nitrate; so-called by the alchemists, among whom "Diana" stood for silver. The arborescence of this amalgam, which even included fruit-like forms on its branches, led pre-modern chemical philosophers to theorize the existence of life in the kingdom of minerals.

Pseudo-Democritus is the name used by scholars for the anonymous authors of a number of Greek writings that were falsely attributed to the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus (c. 460–370 BC).

Nuclear transmutation is the conversion of one chemical element or an isotope into another chemical element. Nuclear transmutation occurs in any process where the number of protons or neutrons in the nucleus of an atom is changed.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to alchemy:

Fulcanelli was the name used by a French alchemist and esoteric author, whose identity is still debated. The name Fulcanelli seems to be a play on words: Vulcan, the ancient Roman god of fire, plus El, a Canaanite name for God and so the Sacred Fire.

Waidan, translated as 'external alchemy' or 'external elixir', is the early branch of Chinese alchemy that focuses upon compounding elixirs of immortality by heating minerals, metals, and other natural substances in a luted crucible. The later branch of esoteric neidan 'inner alchemy', which borrowed doctrines and vocabulary from exoteric waidan, is based on allegorically producing elixirs within the practitioner's body, through Daoist meditation, diet, and physiological practices. The practice of waidan external alchemy originated in the early Han dynasty, grew in popularity until the Tang (618–907) when neidan began and several emperors died from alchemical elixir poisoning, and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

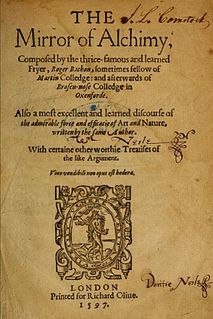

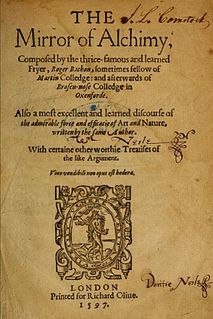

The Mirror of Alchimy is a short alchemical manual, known in Latin as Speculum Alchemiae. Translated in 1597, it was only the second alchemical text printed in the English language. Long ascribed to Roger Bacon (1214-1294), the work is more likely the product of an anonymous author who wrote between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries.

Anna Maria Zieglerin was a sixteenth century alchemist who was found guilty of the murder of a courier, attempted poisoning and intent to burglarize. She was burned alive for her crimes.

In Chinese alchemy, elixir poisoning refers to the toxic effects from elixirs of immortality that contained metals and minerals such as mercury and arsenic. The official Twenty-Four Histories record numerous Chinese emperors, nobles, and officials who died from taking elixirs in order to prolong their lifespans. The first emperor to die from elixir poisoning was likely Qin Shi Huang and the last was Yongzheng. Despite common knowledge that immortality potions could be deadly, fangshi and Daoist alchemists continued the elixir-making practice for two millennia.

Solomon or Salomon Trismosin was a legendary Renaissance alchemist, claimed possessor of the philosopher's stone and teacher of Paracelsus. He is best known as the author of the alchemical works Splendor Solis and Aureum Vellus.