Otosclerosis is a condition of the middle ear where portions of the dense enchondral layer of the bony labyrinth remodel into one or more lesions of irregularly-laid spongy bone. As the lesions reach the stapes the bone is resorbed, then hardened (sclerotized), which limits its movement and results in hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo or a combination of these. The term otosclerosis is something of a misnomer: much of the clinical course is characterized by lucent rather than sclerotic bony changes, so the disease is also known as otospongiosis.

A hearing test provides an evaluation of the sensitivity of a person's sense of hearing and is most often performed by an audiologist using an audiometer. An audiometer is used to determine a person's hearing sensitivity at different frequencies. There are other hearing tests as well, e.g., Weber test and Rinne test.

The acoustic reflex is an involuntary muscle contraction that occurs in the middle ear in response to loud sound stimuli or when the person starts to vocalize.

Conductive hearing loss (CHL) occurs when there is a problem transferring sound waves anywhere along the pathway through the outer ear, tympanic membrane (eardrum), or middle ear (ossicles). If a conductive hearing loss occurs in conjunction with a sensorineural hearing loss, it is referred to as a mixed hearing loss. Depending upon the severity and nature of the conductive loss, this type of hearing impairment can often be treated with surgical intervention or pharmaceuticals to partially or, in some cases, fully restore hearing acuity to within normal range. However, cases of permanent or chronic conductive hearing loss may require other treatment modalities such as hearing aid devices to improve detection of sound and speech perception.

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a type of hearing loss in which the root cause lies in the inner ear, sensory organ, or the vestibulocochlear nerve. SNHL accounts for about 90% of reported hearing loss. SNHL is usually permanent and can be mild, moderate, severe, profound, or total. Various other descriptors can be used depending on the shape of the audiogram, such as high frequency, low frequency, U-shaped, notched, peaked, or flat.

An otoacoustic emission (OAE) is a sound that is generated from within the inner ear. Having been predicted by Austrian astrophysicist Thomas Gold in 1948, its existence was first demonstrated experimentally by British physicist David Kemp in 1978, and otoacoustic emissions have since been shown to arise through a number of different cellular and mechanical causes within the inner ear. Studies have shown that OAEs disappear after the inner ear has been damaged, so OAEs are often used in the laboratory and the clinic as a measure of inner ear health.

Audiometry is a branch of audiology and the science of measuring hearing acuity for variations in sound intensity and pitch and for tonal purity, involving thresholds and differing frequencies. Typically, audiometric tests determine a subject's hearing levels with the help of an audiometer, but may also measure ability to discriminate between different sound intensities, recognize pitch, or distinguish speech from background noise. Acoustic reflex and otoacoustic emissions may also be measured. Results of audiometric tests are used to diagnose hearing loss or diseases of the ear, and often make use of an audiogram.

Auditory neuropathy (AN) is a hearing disorder in which the outer hair cells of the cochlea are present and functional, but sound information is not transmitted sufficiently by the auditory nerve to the brain. The cause may be several dysfunctions of the inner hair cells of the cochlea or spiral ganglion neuron levels. Hearing loss with AN can range from normal hearing sensitivity to profound hearing loss.

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, is the cumulative effect of aging on hearing. It is a progressive and irreversible bilateral symmetrical age-related sensorineural hearing loss resulting from degeneration of the cochlea or associated structures of the inner ear or auditory nerves. The hearing loss is most marked at higher frequencies. Hearing loss that accumulates with age but is caused by factors other than normal aging is not presbycusis, although differentiating the individual effects of distinct causes of hearing loss can be difficult.

An audiogram is a graph that shows the audible threshold for standardized frequencies as measured by an audiometer. The Y axis represents intensity measured in decibels (dB) and the X axis represents frequency measured in hertz (Hz). The threshold of hearing is plotted relative to a standardised curve that represents 'normal' hearing, in dB(HL). They are not the same as equal-loudness contours, which are a set of curves representing equal loudness at different levels, as well as at the threshold of hearing, in absolute terms measured in dB SPL.

An audiometer is a machine used for evaluating hearing acuity. They usually consist of an embedded hardware unit connected to a pair of headphones and a test subject feedback button, sometimes controlled by a standard PC. Such systems can also be used with bone vibrators to test conductive hearing mechanisms.

Hearing range describes the frequency range that can be heard by humans or other animals, though it can also refer to the range of levels. The human range is commonly given as 20 to 20,000 Hz, although there is considerable variation between individuals, especially at high frequencies, and a gradual loss of sensitivity to higher frequencies with age is considered normal. Sensitivity also varies with frequency, as shown by equal-loudness contours. Routine investigation for hearing loss usually involves an audiogram which shows threshold levels relative to a normal.

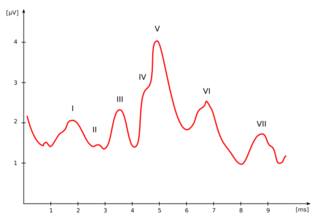

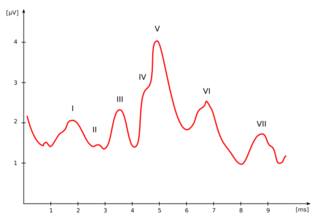

The auditory brainstem response (ABR), also called brainstem evoked response audiometry (BERA) or brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEPs) or brainstem auditory evoked responses (BAERs) is an auditory evoked potential extracted from ongoing electrical activity in the brain and recorded via electrodes placed on the scalp. The measured recording is a series of six to seven vertex positive waves of which I through V are evaluated. These waves, labeled with Roman numerals in Jewett and Williston convention, occur in the first 10 milliseconds after onset of an auditory stimulus. The ABR is considered an exogenous response because it is dependent upon external factors.

In audio signal processing, auditory masking occurs when the perception of one sound is affected by the presence of another sound.

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory science.

Bone-conduction auditory brainstem response or BCABR is a type of auditory evoked response that records neural response from EEG with stimulus transmitted through bone conduction.

Visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) is a key behavioural test for evaluating hearing in young children. First introduced by Liden and Kankkunen in 1969, VRA is a good indicator of how responsive a child is to sound and speech and whether the child is developing awareness to sound as expected. Performed by an audiologist, VRA is the preferred behavioral technique for children that are 6 – 24 months of age. Using classic operant conditioning, a stimulus is presented, which is followed by a 90 degree head turn from midline by the child, resulting in the child being reinforced with an animation. The child is typically seated in a high chair or on a parent's lap while facing forward. A loud speaker or two are situated at 45 or 90 degrees from the child. As the auditory stimulus is presented, the child will naturally search for the sound source, resulting in a head turn and reinforcement is followed shortly after through an animated toy or video next to the speaker where the auditory stimulus was presented. Using VRA, an audiologist can obtain minimal hearing thresholds ranging in frequencies from 250 Hz - 8000 Hz using speakers, headphones, inserts earphones or through a bone conduction transducer and plot them on an audiogram. The results from the audiogram, paired with other objective measures such as a Tympanogram, Otoacoustic emissions testing and/or Auditory Brainstem Response testing can provide further insight into the child's auditory hearing status as well as future treatment plans if deemed necessary. VRA works well until about 18–24 months of age. Above 18–24 months of age, children need more interesting tasks to hold their attention, which is when audiologists introduce Conditioned Play Audiometry.

The tone decay test is used in audiology to detect and measure auditory fatigue. It was developed by Raymond Carhart in 1957. In people with normal hearing, a tone whose intensity is only slightly above their absolute threshold of hearing can be heard continuously for 60 seconds. The tone decay test produces a measure of the "decibels of decay", i.e. the number of decibels above the patient's absolute threshold of hearing that are required for the tone to be heard for 60 seconds. A decay of between 15 and 20 decibels is indicative of cochlear hearing loss. A decay of more than 25 decibels is indicative of damage to the vestibulocochlear nerve.

Acoustic trauma is the sustainment of an injury to the eardrum as a result of a very loud noise. Its scope usually covers loud noises with a short duration, such as an explosion, gunshot or a burst of loud shouting. Quieter sounds that are concentrated in a narrow frequency may also cause damage to specific frequency receptors. The range of severity can vary from pain to hearing loss.

Identification of a hearing loss is usually conducted by a general practitioner medical doctor, otolaryngologist, certified and licensed audiologist, school or industrial audiometrist, or other audiometric technician. Diagnosis of the cause of a hearing loss is carried out by a specialist physician or otorhinolaryngologist.