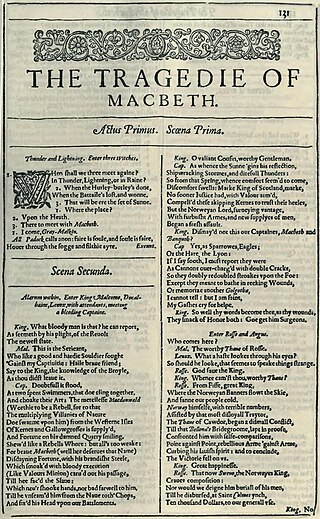

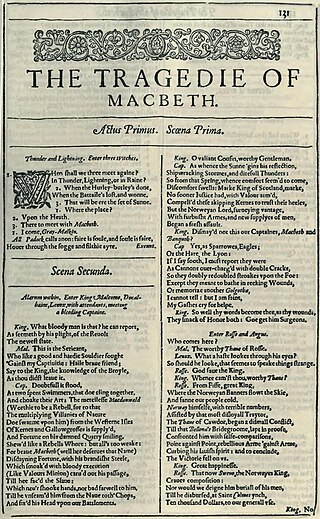

The Tragedy of Macbeth, often shortened to Macbeth, is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the physically violent and damaging psychological effects of political ambitions and power. It was first published in the Folio of 1623, possibly from a prompt book, and is Shakespeare's shortest tragedy. Scholars believe Macbeth, of all the plays that Shakespeare wrote during the reign of King James I, contains the most allusions to James, patron of Shakespeare's acting company.

The Life and Death of King John, often shortened to King John, a history play by William Shakespeare, dramatises the reign of John, King of England, the son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine and the father of Henry III. It is believed to have been written in the mid-1590s, but it was not published until 1623 in the First Folio.

The Life and Death of King Richard the Second, often shortened to Richard II, is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written around 1595. Based on the life of King Richard II of England, it chronicles his downfall and the machinations of his nobles. It is the first part of a tetralogy, referred to by some scholars as the Henriad, followed by three plays about Richard's successors: Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; and Henry V.

David Garrick was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of European theatrical practice throughout the 18th century, and was a pupil and friend of Samuel Johnson. He appeared in several amateur theatricals, and with his appearance in the title role of Shakespeare's Richard III, audiences and managers began to take notice.

The Tragedy of Richard the Third, often shortened to Richard III, is a play by William Shakespeare. It was probably written c. 1592–1594. It is labelled a history in the First Folio, and is usually considered one, but it is sometimes called a tragedy, as in the quarto edition. Richard III concludes Shakespeare's first tetralogy, and depicts the Machiavellian rise to power and subsequent short reign of King Richard III of England.

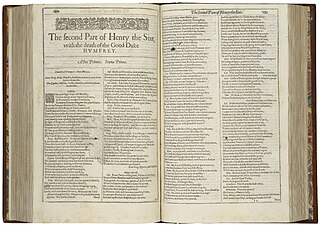

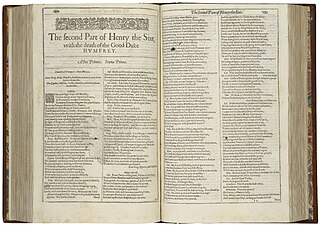

Henry VI, Part 2 is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1591 and set during the lifetime of King Henry VI of England. Whereas Henry VI, Part 1 deals primarily with the loss of England's French territories and the political machinations leading up to the Wars of the Roses, and Henry VI, Part 3 deals with the horrors of that conflict, 2 Henry VI focuses on the King's inability to quell the bickering of his nobles, the death of his trusted adviser Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the rise of the Duke of York and the inevitability of armed conflict. As such, the play culminates with the opening battle of the War, the First Battle of St Albans (1455).

Henry VI, Part 3 is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1591 and set during the lifetime of King Henry VI of England. Whereas 1 Henry VI deals with the loss of England's French territories and the political machinations leading up to the Wars of the Roses and 2 Henry VI focuses on the King's inability to quell the bickering of his nobles, and the inevitability of armed conflict, 3 Henry VI deals primarily with the horrors of that conflict, with the once stable nation thrown into chaos and barbarism as families break down and moral codes are subverted in the pursuit of revenge and power.

Colley Cibber was an English actor-manager, playwright and Poet Laureate. His colourful memoir An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber (1740) describes his life in a personal, anecdotal and even rambling style. He wrote 25 plays for his own company at Drury Lane, half of which were adapted from various sources, which led Robert Lowe and Alexander Pope, among others, to criticise his "miserable mutilation" of "crucified Molière [and] hapless Shakespeare".

Susannah Maria Cibber was a celebrated English singer and actress. She was the sister of the composer Thomas Arne. Although she began her career as a soprano, her voice lowered in the early part of her career to that of a true contralto. She was universally admired for her ability to move her audiences emotionally both as an actress and vocalist. Possessing a sweet, expressive, and agile singing voice with a wide vocal range, Cibber was an immensely popular singer, even if at times her voice was criticized for a lack of polished technique. Charles Burney wrote of her singing that "by a natural pathos, and perfect conception of the words, she often penetrated the heart, when others, with infinitely greater voice and skill, could only reach the ear." Cibber was particularly admired by Handel, who wrote numerous parts especially for her including the contralto arias in his 1741 oratorio Messiah, the role of Micah in Samson, the role of Lichas in Hercules and the role of David in Saul among others. In the mid-1730s she began appearing in plays in addition to appearing in operas and oratorios. She became the greatest dramatic actress of the eighteenth-century London stage and at the time of her death was the highest-paid actress in England.

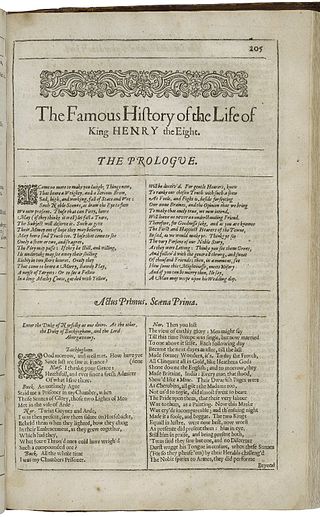

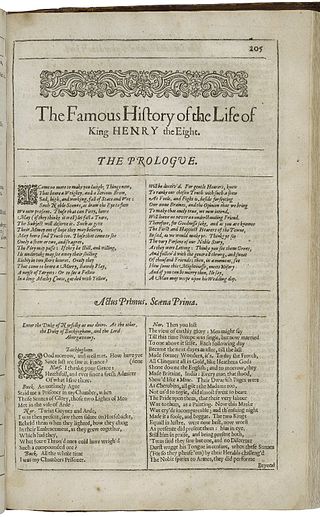

The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eighth, often shortened to Henry VIII, is a collaborative history play, written by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, based on the life of Henry VIII. An alternative title, All Is True, is recorded in contemporary documents, with the title Henry VIII not appearing until the play's publication in the First Folio of 1623. Stylistic evidence indicates that individual scenes were written by either Shakespeare or his collaborator and successor, John Fletcher. It is also somewhat characteristic of the late romances in its structure. It is noted for having more stage directions than any of Shakespeare's other plays.

Richard III is a 1955 British Technicolor film adaptation of William Shakespeare's historical play of the same name, also incorporating elements from his Henry VI, Part 3. It was directed and produced by Laurence Olivier, who also played the lead role. Featuring many noted Shakespearean actors, including a quartet of knights, the film depicts Richard plotting and conspiring to grasp the throne from his brother King Edward IV, played by Sir Cedric Hardwicke. In the process, many are killed and betrayed, with Richard's evil leading to his own downfall. The prologue of the film states that history without its legends would be "a dry matter indeed", implicitly admitting to the artistic licence that Shakespeare applied to the events of the time.

Every Man in His Humour is a 1598 play by the English playwright Ben Jonson. The play belongs to the subgenre of "humours comedy", in which each major character is dominated by an over-riding humour or obsession.

Thomas of Woodstock and Richard the Second Part One are two names for an untitled, anonymous and apparently incomplete manuscript of an Elizabethan play depicting events in the reign of King Richard II. Attributions of the play to William Shakespeare have been nearly universally rejected, and it does not appear in major editions of the Shakespeare apocrypha. The play has been often cited as a possible influence on Shakespeare's Richard II, as well as Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, but new dating of the text brings that relationship into question.

Robert Wilks was a British actor and theatrical manager who was one of the leading managers of Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in its heyday of the 1710s. He was, with Colley Cibber and Thomas Doggett, one of the "triumvirate" of actor-managers that was denounced by Alexander Pope and caricatured by William Hogarth as leaders of the decline in theatrical standards and degradation of the stage's literary tradition.

Augustan drama can refer to the dramas of Ancient Rome during the reign of Caesar Augustus, but it most commonly refers to the plays of Great Britain in the early 18th century, a subset of 18th-century Augustan literature. King George I referred to himself as "Augustus," and the poets of the era took this reference as apropos, as the literature of Rome during Augustus moved from historical and didactic poetry to the poetry of highly finished and sophisticated epics and satire.

The Custom of the Country is a Jacobean stage play, a tragicomedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, originally published in 1647 in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio.

Thousands of performances of William Shakespeare's plays have been staged since the end of the 16th century. While Shakespeare was alive, many of his greatest plays were performed by the Lord Chamberlain's Men and King's Men acting companies at the Globe and Blackfriars Theatres. Among the actors of these original performances were Richard Burbage, Richard Cowley, and William Kempe.

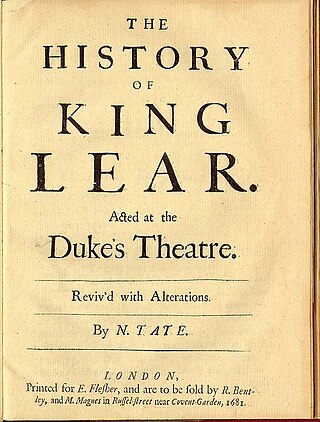

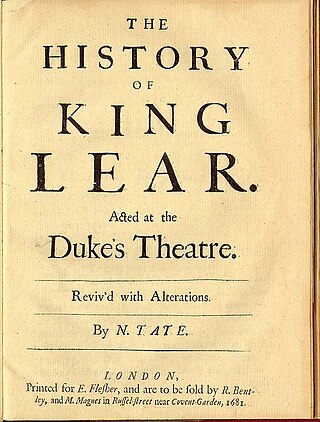

The History of King Lear is an adaptation by Nahum Tate of William Shakespeare's King Lear. It first appeared in 1681, some seventy-five years after Shakespeare's version, and is believed to have replaced Shakespeare's version on the English stage in whole or in part until 1838. While Tate's version proved extremely popular on the stage and received critical acclaim, the response of literary critics has generally been negative.

David Garrick as Richard III is a painting dating from 1745 by the English artist William Hogarth.

The Wars of the Roses was a 1963 theatrical adaptation of William Shakespeare's first historical tetralogy, which deals with the conflict between the House of Lancaster and the House of York over the throne of England, a conflict known as the Wars of the Roses. The plays were adapted by John Barton, and directed by Barton and Peter Hall at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. The production starred David Warner as Henry VI, Peggy Ashcroft as Margaret of Anjou, Donald Sinden as the Duke of York, Paul Hardwick as the Duke of Gloucester, Janet Suzman as Joan la Pucelle, Brewster Mason as the Earl of Warwick, Roy Dotrice as Edward IV, Susan Engel as Queen Elizabeth and Ian Holm as Richard III.