Animism is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases words—as being animated, having agency and free will. Animism is used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many Indigenous peoples in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Animism is a metaphysical belief which focuses on the supernatural universe: specifically, on the concept of the immaterial soul.

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed in the belief that they can manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces. It is a category into which have been placed various beliefs and practices sometimes considered separate from both religion and science.

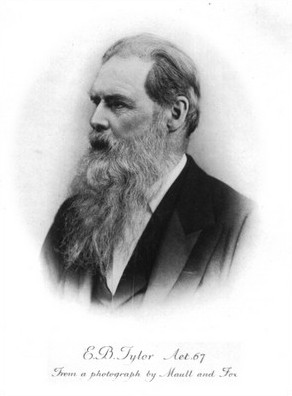

Anthropology of religion is the study of religion in relation to other social institutions, and the comparison of religious beliefs and practices across cultures. The anthropology of religion, as a field, overlaps with but is distinct from the field of Religious Studies. The history of anthropology of religion is a history of striving to understand how other people view and navigate the world. This history involves deciding what religion is, what it does, and how it functions. Today, one of the main concerns of anthropologists of religion is defining religion, which is a theoretical undertaking in and of itself. Scholars such as Edward Tylor, Emile Durkheim, E.E. Evans Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, and Talal Asad have all grappled with defining and characterizing religion anthropologically.

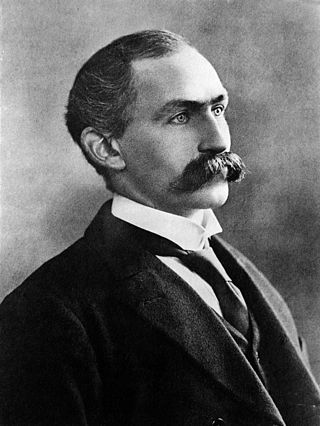

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski was a Polish-British anthropologist and ethnologist whose writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropology.

Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard FBA FRAI was an English anthropologist who was instrumental in the development of social anthropology. He was Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Oxford from 1946 to 1970.

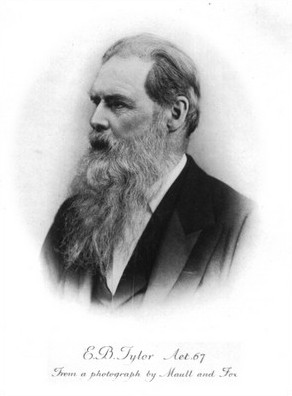

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.

Sir James George Frazer was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, FBA was an English social anthropologist who helped further develop the theory of structural functionalism. He conducted fieldwork in the Andaman Islands and Western Australia, which became the basis of his later books. He held academic appointments at universities in Cape Town, Sydney, Chicago, and Oxford, and sought to use model the field of anthopology after the natural sciences.

Dame Mary Douglas, was a British anthropologist, known for her writings on human culture, symbolism and risk, whose area of speciality was social anthropology. Douglas was considered a follower of Émile Durkheim and a proponent of structuralist analysis, with a strong interest in comparative religion.

Irving R. Hexham is an English-Canadian academic who has published twenty-three books and numerous articles, chapters, and book reviews. Currently, he is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, married to Karla Poewe who is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Calgary, and the father of two children. He holds dual British and Canadian citizenship.

The beliefs and practices of African people are highly diverse, and include various ethnic religions. Generally, these traditions are oral rather than scriptural and are passed down from one generation to another through narratives, songs, and festivals. They include beliefs in spirits and higher and lower gods, sometimes including a supreme being, as well as the veneration of the dead, use of magic, and traditional African medicine. Most religions can be described as animistic with various polytheistic and pantheistic aspects. The role of humanity is generally seen as one of harmonizing nature with the supernatural.

Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah was a social anthropologist and Esther and Sidney Rabb Professor (Emeritus) of Anthropology at Harvard University. He specialised in studies of Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Tamils, as well as the anthropology of religion and politics.

Juju or ju-ju is a spiritual belief system incorporating objects, such as amulets, and spells used in religious practice in West Africa by the people of Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Cameroon. The term has been applied to traditional Western African religions, incorporating objects such as amulets, and spells used in spiritual practices, and blood sacrifices. This is under the belief that two vessels that have been in close physical contact with each other have similar spiritual properties and in turn, makes the objects possible to manipulate.

Sir John Rankine Goody was an English social anthropologist. He was a prominent lecturer at Cambridge University, and was William Wyse Professor of Social Anthropology from 1973 to 1984.

Sociological, psychological, and anthropological theories about religion generally attempt to explain the origin and function of religion. These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of religious belief and practice.

Ethnoscience has been defined as an attempt "to reconstitute what serves as science for others, their practices of looking after themselves and their bodies, their botanical knowledge, but also their forms of classification, of making connections, etc.".

Henry Balfour FRS FRAI was a British archaeologist, and the first curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum.

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In the United States, social anthropology is commonly subsumed within cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology.

Magic, Witchcraft and the Otherworld: An Anthropology is an anthropological study of contemporary Pagan and ceremonial magic groups that practiced magic in London, England, during the 1990s. It was written by English anthropologist Susan Greenwood based upon her doctoral research undertaken at Goldsmiths' College, a part of the University of London, and first published in 2000 by Berg Publishers.

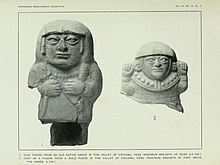

The Duein Fubara is a Nigerian Ancestral Altar Screen.