Carl Edward Sagan was an American astronomer and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by exposure to light. He assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them. He argued in favor of the hypothesis, which has since been accepted, that the high surface temperatures of Venus are the result of the greenhouse effect.

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited. It is not the same as junk science.

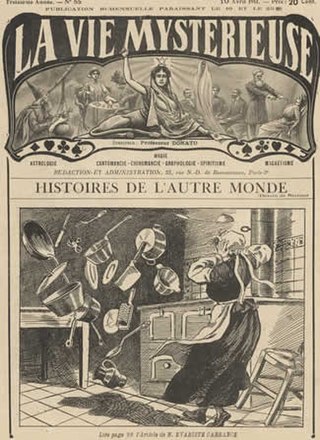

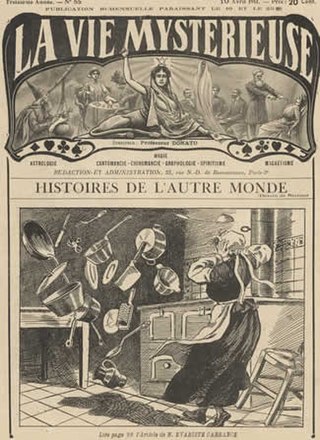

Parapsychology is the study of alleged psychic phenomena and other paranormal claims, for example, those related to near-death experiences, synchronicity, apparitional experiences, etc. Criticized as being a pseudoscience, the majority of mainstream scientists reject it. Parapsychology has also been criticised by mainstream critics for claims by many of its practitioners that their studies are plausible despite a lack of convincing evidence after more than a century of research for the existence of any psychic phenomena.

Telepathy is the purported vicarious transmission of information from one person's mind to another's without using any known human sensory channels or physical interaction. The term was first coined in 1882 by the classical scholar Frederic W. H. Myers, a founder of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), and has remained more popular than the earlier expression thought-transference.

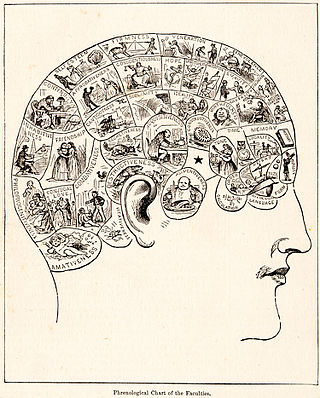

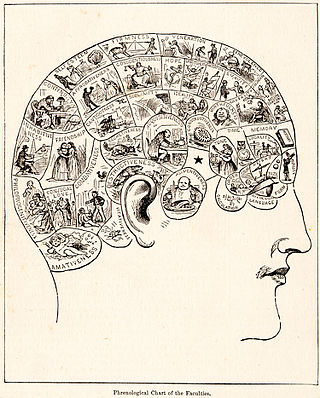

Broca's area, or the Broca area, is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Lynn Margulis was an American evolutionary biologist, and was the primary modern proponent for the significance of symbiosis in evolution. Historian Jan Sapp has said that "Lynn Margulis's name is as synonymous with symbiosis as Charles Darwin's is with evolution." In particular, Margulis transformed and fundamentally framed current understanding of the evolution of cells with nuclei – an event Ernst Mayr called "perhaps the most important and dramatic event in the history of life" – by proposing it to have been the result of symbiotic mergers of bacteria. In 2002, Discover magazine recognized Margulis as one of the 50 most important women in science.

The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), formerly known as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), is a program within the U.S. non-profit organization Center for Inquiry (CFI), which seeks to "promote scientific inquiry, critical investigation, and the use of reason in examining controversial and extraordinary claims." Paul Kurtz proposed the establishment of CSICOP in 1976 as an independent non-profit organization, to counter what he regarded as an uncritical acceptance of, and support for, paranormal claims by both the media and society in general. Its philosophical position is one of scientific skepticism. CSI's fellows have included notable scientists, Nobel laureates, philosophers, psychologists, educators, and authors. It is headquartered in Amherst, New York.

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Notable paranormal beliefs include those that pertain to extrasensory perception, spiritualism and the pseudosciences of ghost hunting, cryptozoology, and ufology.

Scientific skepticism or rational skepticism, sometimes referred to as skeptical inquiry, is a position in which one questions the veracity of claims lacking empirical evidence. In practice, the term most commonly refers to the examination of claims and theories that appear to be beyond mainstream science, rather than the routine discussions and challenges among scientists. Scientific skepticism differs from philosophical skepticism, which questions humans' ability to claim any knowledge about the nature of the world and how they perceive it, and the similar but distinct methodological skepticism, which is a systematic process of being skeptical about the truth of one's beliefs.

HIV/AIDS denialism is the belief, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Some of its proponents reject the existence of HIV, while others accept that HIV exists but argue that it is a harmless passenger virus and not the cause of AIDS. Insofar as they acknowledge AIDS as a real disease, they attribute it to some combination of sexual behavior, recreational drugs, malnutrition, poor sanitation, haemophilia, or the effects of the medications used to treat HIV infection (antiretrovirals).

Philip Hauge Abelson was an American physicist, scientific editor and science writer. Trained as a nuclear physicist, he co-discovered the element neptunium, worked on isotope separation in the Manhattan Project, and wrote the first study of nuclear marine propulsion for submarines. He later worked on a broad range of scientific topics and related public policy, including organic geochemistry, paleobiology and energy policy.

Pseudoskepticism is a philosophical or scientific position that appears to be that of skepticism or scientific skepticism but in reality is a form of dogmatism.

Marcello Truzzi was an American sociologist and academic who was professor of sociology at New College of Florida and later at Eastern Michigan University, founding co-chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), a founder of the Society for Scientific Exploration, and director for the Center for Scientific Anomalies Research.

Evidence of absence is evidence of any kind that suggests something is missing or that it does not exist. What counts as evidence of absence has been a subject of debate between scientists and philosophers. It is often distinguished from absence of evidence.

Telekinesis is a hypothetical psychic ability allowing an individual to influence a physical system without physical interaction. Experiments to prove the existence of telekinesis have historically been criticized for lack of proper controls and repeatability. There is no reliable evidence that telekinesis is a real phenomenon, and the topic is generally regarded as pseudoscience.

In philosophy, a razor is a principle or rule of thumb that allows one to eliminate unlikely explanations for a phenomenon, or avoid unnecessary actions.

The Centre for Inquiry Canada (CFIC) is a not-for-profit educational organization with headquarters in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The Canadian organization was founded as a member and volunteer driven organization in 2007. It is the Canadian affiliate of CFI Transnational. Their primary mission is to provide education and training to the public in the application of skeptical, secular, rational and humanistic inquiry through conferences, symposia, lectures, published works and the maintenance of a library.

Hitchens's razor is an epistemological razor that serves as a general rule for rejecting certain knowledge claims. It states "what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." The razor was created by and later named after author and journalist Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011). It implies that the burden of proof regarding the truthfulness of a claim lies with the one who makes the claim; if this burden is not met, then the claim is unfounded, and its opponents need not argue further in order to dismiss it. Hitchens used this phrase specifically in the context of refuting religious belief.