The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before being removed by defecation. The colon is the longest portion of the large intestine, and the terms are often used interchangeably but most sources define the large intestine as the combination of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal. Some other sources exclude the anal canal.

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum. Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel movements, weight loss, abdominal pain and fatigue. Most colorectal cancers are due to old age and lifestyle factors, with only a small number of cases due to underlying genetic disorders. Risk factors include diet, obesity, smoking, and lack of physical activity. Dietary factors that increase the risk include red meat, processed meat, and alcohol. Another risk factor is inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Some of the inherited genetic disorders that can cause colorectal cancer include familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer; however, these represent less than 5% of cases. It typically starts as a benign tumor, often in the form of a polyp, which over time becomes cancerous.

Colonoscopy or coloscopy is a medical procedure involving the endoscopic examination of the large bowel (colon) and the distal portion of the small bowel. This examination is performed using either a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera, which is mounted on a flexible tube and passed through the anus.

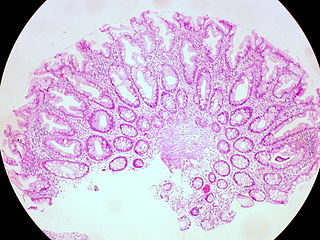

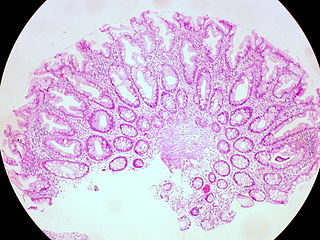

A polyp is an abnormal growth of tissue projecting from a mucous membrane. If it is attached to the surface by a narrow elongated stalk, it is said to be pedunculated; if it is attached without a stalk, it is said to be sessile. Polyps are commonly found in the colon, stomach, nose, ear, sinus(es), urinary bladder, and uterus. They may also occur elsewhere in the body where there are mucous membranes, including the cervix, vocal folds, and small intestine. Some polyps are tumors (neoplasms) and others are non-neoplastic, for example hyperplastic or dysplastic, which are benign. The neoplastic ones are usually benign, although some can be pre-malignant, or concurrent with a malignancy.

An adenoma is a benign tumor of epithelial tissue with glandular origin, glandular characteristics, or both. Adenomas can grow from many glandular organs, including the adrenal glands, pituitary gland, thyroid, prostate, and others. Some adenomas grow from epithelial tissue in nonglandular areas but express glandular tissue structure. Although adenomas are benign, they should be treated as pre-cancerous. Over time adenomas may transform to become malignant, at which point they are called adenocarcinomas. Most adenomas do not transform. However, even though benign, they have the potential to cause serious health complications by compressing other structures and by producing large amounts of hormones in an unregulated, non-feedback-dependent manner. Some adenomas are too small to be seen macroscopically but can still cause clinical symptoms.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant inherited condition in which numerous adenomatous polyps form mainly in the epithelium of the large intestine. While these polyps start out benign, malignant transformation into colon cancer occurs when they are left untreated. Three variants are known to exist, FAP and attenuated FAP are caused by APC gene defects on chromosome 5 while autosomal recessive FAP is caused by defects in the MUTYH gene on chromosome 1. Of the three, FAP itself is the most severe and most common; although for all three, the resulting colonic polyps and cancers are initially confined to the colon wall. Detection and removal before metastasis outside the colon can greatly reduce and in many cases eliminate the spread of cancer.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by the development of benign hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract and hyperpigmented macules on the lips and oral mucosa (melanosis). This syndrome can be classed as one of various hereditary intestinal polyposis syndromes and one of various hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. It has an incidence of approximately 1 in 25,000 to 300,000 births.

Virtual colonoscopy is the use of CT scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to produce two- and three-dimensional images of the colon, from the lowest part, the rectum, to the lower end of the small intestine, and to display the images on an electronic display device. The procedure is used to screen for colon cancer and polyps, and may detect diverticulosis. A virtual colonoscopy can provide 3D reconstructed endoluminal views of the bowel. VC provides a secondary benefit of revealing diseases or abnormalities outside the colon.

Fundic gland polyposis is a medical syndrome where the fundus and the body of the stomach develop many fundic gland polyps. The condition has been described both in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and attenuated variants (AFAP), and in patients in whom it occurs sporadically.

Colonic polypectomy is the removal of colorectal polyps in order to prevent them from turning cancerous.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic condition characterized by the appearance of multiple juvenile polyps in the gastrointestinal tract. Polyps are abnormal growths arising from a mucous membrane. These usually begin appearing before age 20, but the term juvenile refers to the type of polyp, not to the age of the affected person. While the majority of the polyps found in juvenile polyposis syndrome are non-neoplastic, hamartomatous, self-limiting and benign, there is an increased risk of adenocarcinoma.

A colorectal polyp is a polyp occurring on the lining of the colon or rectum. Untreated colorectal polyps can develop into colorectal cancer.

A sessile serrated lesion (SSL) is a premalignant flat lesion of the colon, predominantly seen in the cecum and ascending colon.

A hyperplastic polyp is a type of gastric polyp or colorectal polyp.

The colorectal adenoma is a benign glandular tumor of the colon and the rectum. It is a precursor lesion of the colorectal adenocarcinoma. They often manifest as colorectal polyps.

MUTYH-associated polyposis is an autosomal recessive polyposis syndrome. The disorder is caused by mutations in both alleles of the DNA repair gene, MUTYH. The MUTYH gene encodes a base excision repair protein, which corrects oxidative damage to DNA. Affected individuals have an increased risk of colorectal cancer, precancerous colon polyps (adenomas) and an increased risk of several additional cancers. About 1–2 percent of the population possess a mutated copy of the MUTYH gene, and less than 1 percent of people have the MUTYH-associated polyposis syndrome. The presence of 10 or more colon adenomas should prompt consideration of MUTYH-associated polyposis, familial adenomatous polyposis and similar syndromes.

The histopathology of colorectal cancer of the adenocarcinoma type involves analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report contains a description of the microscopical characteristics of the tumor tissue, including both tumor cells and how the tumor invades into healthy tissues and finally if the tumor appears to be completely removed. The most common form of colon cancer is adenocarcinoma, constituting between 95% and 98% of all cases of colorectal cancer. Other, rarer types include lymphoma, adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma. Some subtypes have been found to be more aggressive.

Polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis (PPAP) is an autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome, which is characterized by numerous polyps in the colon and an increased risk of colorectal cancer. It is caused by germline mutations in DNA polymerase ε (POLE) and δ (POLD1). Affected individuals develop numerous polyps called colorectal adenomas. Compared with other polyposis syndromes, Polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis is rare. Genetic testing can help exclude similar syndromes, such as Familial adenomatous polyposis and MUTYH-associated polyposis. Endometrial cancer, duodenal polyps and duodenal cancer may also occur.

Traditional serrated adenoma is a premalignant type of polyp found in the colon, often in the distal colon. Traditional serrated adenomas are a type of serrated polyp, and may occur sporadically or as a part of serrated polyposis syndrome. Traditional serrated adenomas are relatively rare, accounting for less than 1% of all colon polyps. Usually, traditional serrated adenomas are found in the distal colon and are usually less than 10 mm in size.

Juvenile polyps are a type of polyp found in the colon. While juvenile polyps are typically found in children, they may be found in people of any age. Juvenile polyps are a type of hamartomatous polyps, which consist of a disorganized mass of tissue. They occur in about two percent of children. Juvenile polyps often do not cause symptoms (asymptomatic); when present, symptoms usually include gastrointestinal bleeding and prolapse through the rectum. Removal of the polyp (polypectomy) is warranted when symptoms are present, for treatment and definite histopathological diagnosis. In the absence of symptoms, removal is not necessary. Recurrence of polyps following removal is relatively common. Juvenile polyps are usually sporadic, occurring in isolation, although they may occur as a part of juvenile polyposis syndrome. Sporadic juvenile polyps may occur in any part of the colon, but are usually found in the distal colon. In contrast to other types of colon polyps, juvenile polyps are not premalignant and are not usually associated with a higher risk of cancer; however, individuals with juvenile polyposis syndrome are at increased risk of gastric and colorectal cancer. Unlike juvenile polyposis syndrome, solitary juvenile polyps do not require follow up with surveillance colonoscopy.