The Battle of Diu was a naval battle fought on 3 February 1509 in the Arabian Sea, in the port of Diu, India, between the Portuguese Empire and a joint fleet of the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt and the Zamorin of Calicut.

Rajasinghe I also known as the lion of Sitawaka was a king of Sitawaka, known for his patriotism and fight against the Portuguese invasion of Sri Lanka. Born as Tikiri Bandara to King Mayadunne, he received the name "Rajasinha" after the fierce Battle of Mulleriyawa.

The Kingdom of Sitawaka was a kingdom located in south-central Sri Lanka. It emerged from the division of the Kingdom of Kotte following the Spoiling of Vijayabahu in 1521. Over the course of the next seventy years it came to dominate much of the island. Sitawaka also offered fierce resistance to the Portuguese, who had arrived on the island in 1505. Despite its military successes, Sitawaka remained unstable, having to contend with repeated uprisings in its restive Kandyan territories, as well as a wide-ranging and often devastating conflict with the Portuguese. Sitawaka disintegrated soon after the death of its last king Rajasimha I in 1593.

Maligawatta is a suburb in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Maligawatta is located approximately 3 km (1.9 mi) north-east from the centre of Colombo, Colombo Fort. The name Maligawatta is from the Sinhalese language which translates into garden of the palace.

The siege of Diu occurred when an army of the Sultanate of Gujarat under Khadjar Safar, aided by forces of the Ottoman Empire, attempted to capture the city of Diu in 1538, then held by the Portuguese. The siege was part of the Ottoman-Portuguese war. The Portuguese successfully resisted the four-month long siege.

Dom Jerónimo de Azevedo was a Portuguese fidalgo, Governor (captain-general) of Portuguese Ceylon and viceroy of Portuguese India. He proclaimed in Colombo, in 1597, the King of Portugal, Philip I, as the legitimate heir to the throne of Kotte, thus substantiating the Portuguese claims of sovereignty over the island of Ceylon.

The Battle of the Gulf of Oman was a naval battle between a large Portuguese armada under Dom Fernando de Meneses and the Ottoman Indian fleet under Seydi Ali Reis. The campaign was a catastrophic failure for the Ottomans who lost all of their ships.

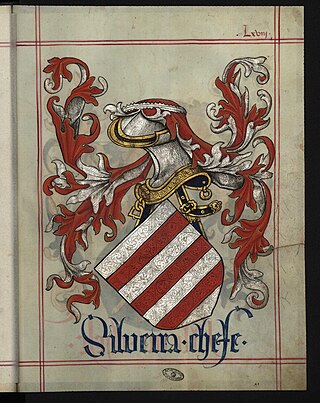

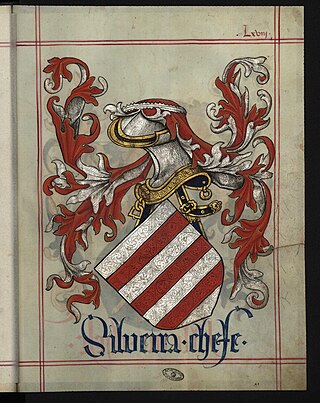

João da Silveira was the first Captain of Portuguese Ceylon. Silveira was appointed in 1518 under Manuel I of Portugal. He was succeeded by Lopo de Brito.

Lopo de Brito was the second Captain of Portuguese Ceylon. Brito succeeded João da Silveira and was appointed in 1518 under Manuel I of Portugal, he was Captain until 1522. He was succeeded by Fernão Gomes de Lemos.

Fernão Gomes de Lemos was the third and last Captain of Portuguese Ceylon. Lemos succeeded Lopo de Brito and was appointed in 1522 under John III of Portugal, he was Captain until 1524. In 1524 when he left as Captain, the office was left vacant until 1551, where the office was succeeded by Captain-majors of Portuguese Ceylon. He was also Portuguese Ambassador to Persia, appointed by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1515.

João de Correia de Brito was the 15th Captain-major of Portuguese Ceylon. Brito was appointed in 1583 under Philip I of Portugal, he was Captain-major until 1590. He was succeeded by Simão de Brito.

The siege of Kotte was an offensive which took place during the Sinhalese–Portuguese War between 1557 and 1558. A 50,000-strong Sitawaka army led by King Mayadunne besieged Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte, the capital of Kotte Kingdom, for 12 months against a combined force of Portuguese and Lascarins led by Captain-major Dom Afonso Pereira de Lacerda. After receiving reinforcements from Mannar, Portuguese made a sally and succeeded in forcing the besiegers to withdraw. This siege marked the beginning of a series of battles between Portuguese and Sitawaka forces, and ultimately ended as Portuguese abandoned Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte in 1565.

Pedro Lopes de Sousa was the 1st Governor of Portuguese Ceylon. The office of Captain-major was abolished in 1594 and de Sousa was appointed in the same year under Philip I of Portugal. He died that year in the Campaign of Danture.

The Danture campaign comprised a series of encounters between the Portuguese and the Kingdom of Kandy in 1594, part of the Sinhalese–Portuguese War. It is considered a turning point in the indigenous resistance to Portuguese expansion. For the first time in Sri Lanka a Portuguese army was essentially annihilated, when they were on the verge of the total conquest of the island. A 20,000-strong Portuguese army, led by Governor Pedro Lopes de Sousa, invaded Kandy on 5 July 1594. After three months, severely depleted by guerilla warfare and mass desertions, what remained of the Portuguese army was annihilated at Danture by the Kandyans under King Vimaladharmasuriya. With this victory, the Kingdom of Kandy emerged as a major military power; it was to retain its independence, against Portuguese, Dutch, and British armies, until 1815.

The Siege of the Portuguese fort Santa Cruz de Gale at Galle in 1640, took place during the Dutch–Portuguese and Sinhalese–Portuguese Wars. The Galle fort commanded 282 villages, which contained most fertile cinnamon lands in southern Sri Lanka It was also an important strategic coastal defense of Portuguese Ceylon. The Dutch, who were in an alliance with the Kingdom of Kandy, landed an expeditionary force under Commodore Willem Jacobszoon Coster of Akersloot, at the Bay of Galle, on 8 March 1640. After bombarding the fort for four consecutive days, Dutch troops stormed the fort and secured a victory on 13 March 1640. The Portuguese garrison, led by Captain Lourenço Ferreira de Brito, mounted a stiff resistance and unexpectedly high casualty rates among Dutch troops gave rise to the proverb “Gold in Malacca, lead in Galle”. With this victory the Dutch gained access to a large port which they later used as a convenient naval base to attack Goa and other South Indian Portuguese defenses. They also gained access to the Sri Lankan cinnamon trade and gained a permanent foothold on the island.

Sinhalese–Portuguese conflicts refers to the series of armed engagements that took place from 1518 to 1658 in Sri Lanka between the native Sinhalese and Tamil kingdoms and the Portuguese Empire. It spanned from the Transitional to the Kandyan periods of Sri Lankan history. A combination of political and military moves gained the Portuguese control over most of the island, but their invasion of the final independent kingdom was a disaster, leading to a stalemate in the wider war and a truce from 1621. In 1638 the war restarted when the Dutch East India Company intervened in the conflict, initially as an ally of the Sinhalese against the Portuguese, but later as an enemy of both sides. The war concluded in 1658, with the Dutch in control of about half the island, the Kingdom of Kandy the other half, and the Portuguese expelled.

André Furtado de Mendonça was a captain and governor of Portuguese India, and a military commander during Portuguese expansion into Ceylon, India, Indonesia and Malacca.

The War of the League of the Indies was a military conflict in which a pan-Asian alliance formed primarily by the Sultanate of Bijapur, the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar, the Kingdom of Calicut, and the Sultanate of Aceh, referred to by the Portuguese historian António Pinto Pereira as the "league of kings of India", "the confederated kings", or simply "the league", attempted to decisively overturn Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean through a combined assault on some of the main possessions of the Portuguese State of India: Malacca, Chaul, Chale fort, and the capital of the maritime empire in Asia, Goa.

The siege of Bahrain of 1559 occurred when forces of the Ottoman Empire, commanded by the governor of the Lahsa eyalet Mustafa Pasha, attempted to seize Bahrain, and thus wrest control of the island and its famed pearl trade from the Portuguese Empire. The siege was unsuccessful, and the Portuguese defeated the Turks when reinforcements were dispatched by sea from the fortress of Hormuz.

Kuruvita Rala was a Sri Lankan rebel leader and prince of Uva, who served as regent in the kingdom of Kandy. He was also a relation of Dona Catherina, Queen of Kandy and the guardian of her children.