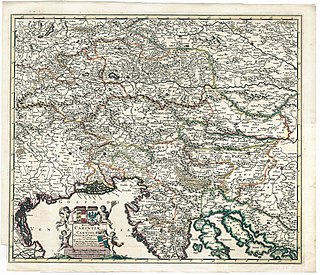

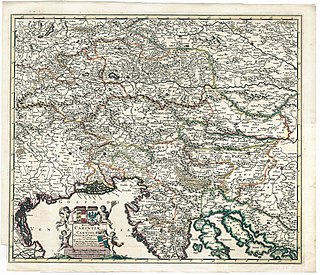

The history of Slovenia chronicles the period of the Slovenian territory from the 5th century BC to the present. In the Early Bronze Age, Proto-Illyrian tribes settled an area stretching from present-day Albania to the city of Trieste. The Slovenian territory was part of the Roman Empire, and it was devastated by the Migration Period's incursions during late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The main route from the Pannonian plain to Italy ran through present-day Slovenia. Alpine Slavs, ancestors of modern-day Slovenians, settled the area in the late 6th Century AD. The Holy Roman Empire controlled the land for nearly 1,000 years, and between the mid-14th century and 1918 most of Slovenia was under Habsburg rule. In 1918, Slovenes formed Yugoslavia along with Serbs and Croats, while a minority came under Italy. The state of Slovenia was created in 1945 as part of federal Yugoslavia. Slovenia gained its independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, and is today a member of the European Union and NATO.

Slovene, or alternatively Slovenian, is a South Slavic language, a sub-branch that is part of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is spoken by about 2.5 million speakers worldwide, mainly ethnic Slovenes, the majority of whom live in Slovenia, where it is the sole official language. As Slovenia is part of the European Union, Slovene is also one of its 24 official and working languages.

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians, are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their native language. They are closely related to other South Slavic ethnic groups, especially Croats, as well as more distantly to West Slavs.

"Naprej, zastava slave" or "Naprej, zastava Slave" is a former national anthem of Slovenia, used from 1860 to 1989. It is now used as the official service song of the Slovenian Armed Forces.

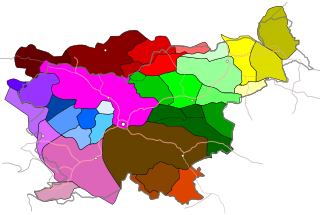

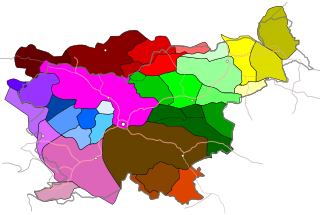

Slovenj Gradec is a city in northern Slovenia. It is the centre of the City Municipality of Slovenj Gradec. It is part of the historical Styria region, and since 2005 it has belonged to the NUTS-3 Carinthia Statistical Region. It is located in the Mislinja Valley at the eastern end of the Karawanks mountain range, about 45 km (28 mi) west of Maribor and 65 km (40 mi) northeast of Ljubljana.

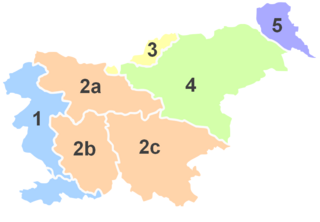

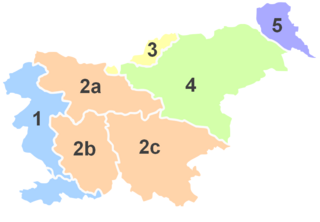

Prekmurje is a geographically, linguistically, culturally and ethnically defined region of Slovenia, settled by Slovenes and a Hungarian minority, lying between the Mur River in Slovenia and the Rába Valley in the westernmost part of Hungary. It maintains certain specific linguistic, cultural and religious features that differentiate it from other Slovenian traditional regions. It covers an area of 938 square kilometers (362 sq mi) and has a population of 78,000 people.

Styria, also Slovenian Styria or Lower Styria, is a traditional region in northeastern Slovenia, comprising the southern third of the former Duchy of Styria. The population of Styria in its historical boundaries amounts to around 705,000 inhabitants, or 34.5% of the population of Slovenia. The largest city is Maribor.

United Slovenia is the name originally given to an unrealized political programme of the Slovene national movement, formulated during the Spring of Nations in 1848. The programme demanded (a) unification of all the Slovene-inhabited areas into one single kingdom under the rule of the Austrian Empire, (b) equal rights of Slovene in public, and (c) strongly opposed the planned integration of the Habsburg monarchy with the German Confederation. The programme failed to meet its main objectives, but it remained the common political program of all currents within the Slovene national movement until World War I.

Carinthian Slovenes or Carinthian Slovenians are the indigenous minority of Slovene ethnicity, living within borders of the Austrian state of Carinthia, neighboring Slovenia. Their status of the minority group is guaranteed in principle by the Constitution of Austria and under international law, and have seats in the National Ethnic Groups Advisory Council.

Hungarian Slovenes are an autochthonous ethnic and linguistic Slovene minority living in Hungary. The largest groups are the Rába Slovenes in the Rába Valley in Hungary between the town of Szentgotthárd and the borders with Slovenia and Austria. They speak the Prekmurje Slovene dialect. Outside the Rába Valley, Slovenes mainly live in the Szombathely region and in Budapest.

Gregorij Rožman was a Slovenian Roman Catholic prelate. Between 1930 and 1959, he served as bishop of the Diocese of Ljubljana. He may be best-remembered for his controversial role during World War II. Rožman was an ardent anti-communist and opposed the Liberation Front of the Slovene People and the Partisan forces because they were led by the Communist party. He established relations with both the fascist and Nazi occupying powers, issued proclamations of support for the occupying authorities, and supported armed collaborationist forces organized by the fascist and Nazi occupiers. The Yugoslav Communist government convicted him in absentia in August 1946 of treason for collaborating with the Nazis against the Yugoslav resistance. In 2009, his conviction was annulled on procedural grounds.

Mihály Bakos, also known in Slovene as Miháo Bakoš or Mihael Bakoš, was a Hungarian Slovene Lutheran priest, author, and educator.

Prekmurje Slovene, also known as the Prekmurje dialect, East Slovene, or Wendish, is a Slovene dialect belonging to a Pannonian dialect group of Slovene. It is used in private communication, liturgy, and publications by authors from Prekmurje. It is spoken in the Prekmurje region of Slovenia and by the Hungarian Slovenes in Vas County in western Hungary. It is closely related to other Slovene dialects in neighboring Slovene Styria, as well as to Kajkavian with which it retains partial mutual intelligibility and forms a dialect continuum with other South Slavic languages.

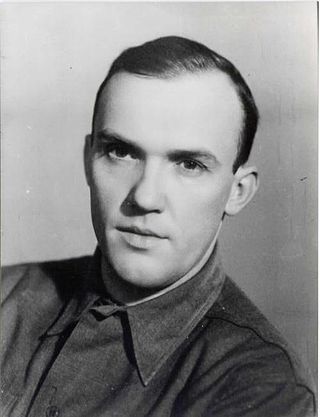

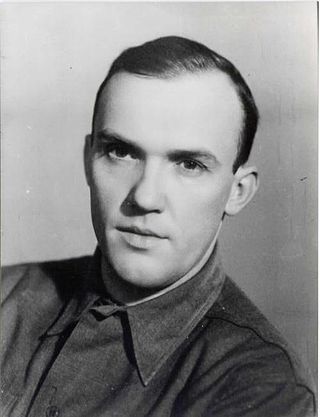

Matej Bor was the pen name of Vladimir Pavšič, who was a Slovene poet, translator, playwright, journalist, and Partisan.

Radenska is a Slovenia-based worldwide known brand of mineral water, trademark of Radenska d.o.o. company. It is one of the oldest Slovenian brands.

The Slovene Society is the second-oldest publishing house in Slovenia, founded on February 4, 1864 as an institution for the scholarly and cultural progress of Slovenes.

Contributions to the Slovene National Program, also known as Nova revija 57 or 57th edition of Nova revija was a special issue of the Slovene opposition intellectual journal Nova revija, published in January 1987. It contained 16 articles by non-Communist and anti-Communist dissidents in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, discussing the possibilities and conditions for the democratization of Slovenia and the achievement of full sovereignty. It was issued as a reaction to the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts and to the rising centralist aspirations within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

The Slovene Partisans, formally the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Slovenia, were part of Europe's most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement led by Yugoslav revolutionary communists during World War II, the Yugoslav Partisans. Since a quarter of Slovene ethnic territory and approximately 327,000 out of total population of 1.3 million Slovenes were subjected to forced Italianization since the end of the First World War, the objective of the movement was the establishment of the state of Slovenes that would include the majority of Slovenes within a socialist Yugoslav federation in the postwar period.

Slovene minority in Italy, also known as Slovenes in Italy is the name given to Italian citizens who belong to the autochthonous Slovene ethnic and linguistic minority living in the Italian autonomous region of Friuli – Venezia Giulia. The vast majority of members of the Slovene ethnic minority live in the Provinces of Trieste, Gorizia, and Udine. Estimates of their number vary significantly; the official figures show 52,194 Slovenian speakers in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as per the 1971 Census, but Slovenian estimates speak of 83,000 to 100,000 people.

Slovene communities in South America refer to groups of people of Slovene ancestry living in various countries of South America. The first Slovenes arrived in South America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily from the Slovene Littoral region, and settled in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Slovenes arrived in South America for various reasons, including economic opportunities and political turmoil in Slovenia at the time. Many Slovenes found work in agriculture, industry, and trade in South America, and were able to build successful lives for themselves and their families.