The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloody Civil War, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and to reinstate the political, social, and economic legacies of slavery.

Logan County is a county in the southwest Pennyroyal Plateau area of the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,432. Its county seat is Russellville.

Statesboro is the largest city and county seat of Bulloch County, Georgia, United States, located in the southeastern part of the state.

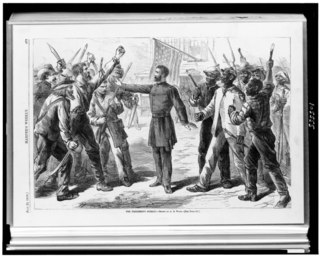

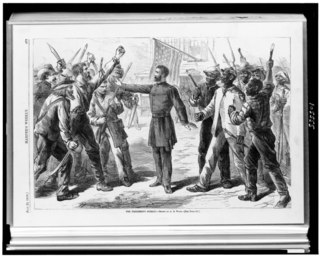

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a U.S. government agency, from 1865 to 1872, after the American Civil War, to direct "provisions, clothing, and fuel...for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children".

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans. In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and many Northern states had them, it was the Democrat-led Southern U.S. states that codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of them were passed in 1865 and 1866 by Southern states, after the American Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and to compel them to work for low or no wages.

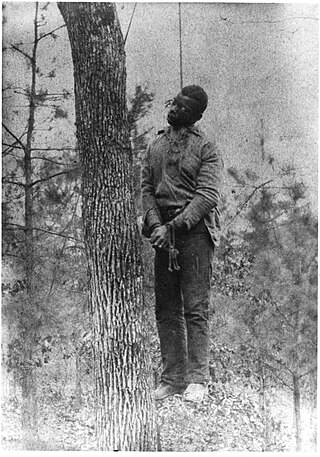

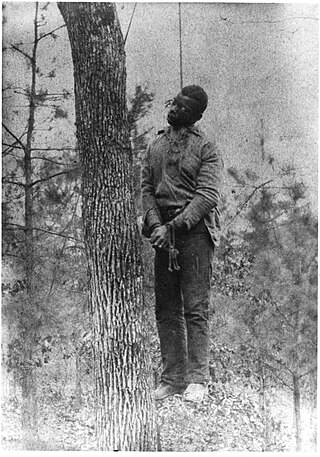

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimised ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South because the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African-American history and the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century, when racism in the country, especially anti-black racism, was more open and pronounced than it had ever been during any other period in the nation's history. During this period, African Americans lost access to many of the civil rights they had gained during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynchings, segregation, legalized racial discrimination, and expressions of white supremacy all increased.

The Pickens County Courthouse in the county seat of Carrollton, Alabama is the courthouse for Pickens County, Alabama. Built-in 1877-1878 as the third courthouse in the city, it is noted for a ghostly image that can be seen in one of its garret windows. This is claimed to be the face of freedman Henry Wells from 1878.

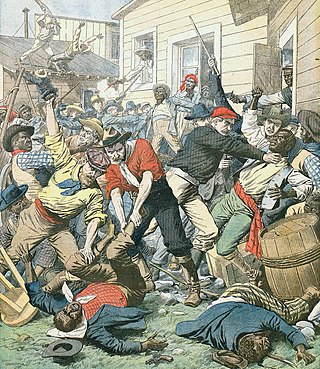

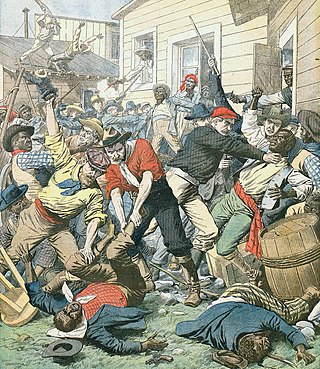

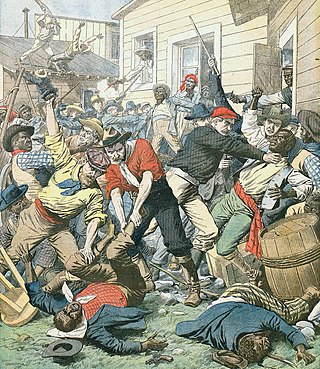

Violent reprisals by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after a group of black men supposedly raped 4 women on the evening of September 22, 1906, and lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

West Union (Busro) is an abandoned Shaker community in Busseron Township, northwestern Knox County, Indiana, about fifteen miles (24 km) north of Vincennes. The settlement was inhabited by the Shakers from 1811 to 1827. Though short-lived, West Union was the westernmost Shaker settlement.

Triune is an unincorporated community in eastern Williamson County, Tennessee, approximately halfway between Franklin and Murfreesboro. The community is located along the Wilson Branch of the Harpeth River. The intersection of former local roads State Route 96 and the concurrency of U.S. Routes 31A and 41A is here. The community is located just north of these roads interchange with Interstate 840.

The Meridian race riot of 1871 was a race riot in Meridian, Mississippi in March 1871. It followed the arrest of freedmen accused of inciting riot in a downtown fire, and blacks' organizing for self-defense. Although the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) chapter had attacked freedmen since the end of the Civil War, generally without punishment, the first local arrest under the 1870 act to suppress the Klan was of a freedman. This angered the black community. During the trial of black leaders, the presiding judge was shot in the courtroom, and a gunfight erupted that killed several people. In the ensuing mob violence, whites killed as many as 30 blacks over the next few days. Democrats drove the Republican mayor from office, and no person was charged or tried in the freedmen's deaths.

In Forsyth County, Georgia, in September 1912 two separate alleged attacks on white women resulted in black men being accused as suspects. One white woman accused two black men of breaking into her home in Big Creek Community and one of raping her. Another teenage woman was fatally beaten and raped in the Oscarville Community. Earnest Knox was linked to the Oscarville murder along with his half brother by a hair comb sold to him at the Oscarville store. When confronted, he confessed to the Sheriff and implicated his half brother and mother’s live-in boyfriend. His mother testified against the sons during the jury trial which sentenced both to hanging. 21 days later the sentence was carried out.

The Longview race riot was a series of violent incidents in Longview, Texas, between July 10 and July 12, 1919, when whites attacked black areas of town, killed one black man, and burned down several properties, including the houses of a black teacher and a doctor. It was one of the many race riots in 1919 in the United States during what became known as Red Summer, a period after World War I known for numerous riots occurring mostly in urban areas.

Joe Pullen or Joe Pullum was an African-American tenant farmer who was murdered by a lynch mob of local white citizens near Drew, Mississippi on December 15, 1923. While the circumstances that precipitated the violence were typical for that place and time, Pullen's case is unusual in that he managed to kill at least three members of the lynch mob and wound several others before ultimately perishing himself. Because of his courage, Pullen became a folk hero and his bravery was championed by the Universal Negro Improvement Association. While the incident received only brief national news coverage, the local repercussions were far more profound. As civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer recalled in an autobiographical essay on growing up in a nearby Mississippi town: "it was a while in Mississippi before the whites tried something like that again."

The lynching of the Walker family took place near Hickman, Fulton County, Kentucky, on October 3, 1908, at the hands of about fifty masked Night Riders. David Walker was a landowner, with a 21.5-acre (8.7 ha) farm. The entire family of seven African Americans, parents, infant in arms, and four children, was reported killed, with the event carried by national newspapers. Governor Augustus E. Willson of Kentucky strongly condemned the murders and promised a reward for information leading to prosecution. No one was ever prosecuted.

The 1866 Gallatin County Race Riot took place from August 3 past August 13 a year after the close of the American Civil War in Gallatin County, Kentucky. It was part of waves of violence by whites against blacks in the state, and even in northern Kentucky, where the black population was relatively small. According to historians Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter, "A band of five hundred whites in Gallatin County... forced hundreds of blacks to flee across the Ohio River."

The lynching of Marie Thompson of Shepherdsville took place in the early morning on June 15, 1904, in Lebanon Junction, Bullitt County, Kentucky, for her killing of John Irvin, a white landowner. The day before Thompson had attempted to defend her son from being beaten by Irvin in a dispute; he ordered her off the land. As she was walking away from him, he attacked her with a knife and she killed him in self-defense with a razor. She was arrested and put in the county jail.

George Dinning was an American former slave from Simpson County, Kentucky. In 1897, during self-defense of his home from an armed mob, he shot and killed the son of a wealthy white landowner. He was convicted of manslaughter, but was soon pardoned by Kentucky Governor William O'Connell Bradley. Dinning then successfully sued members of the Ku Klux Klan over the incident. His plight and case was followed in the national press; the public was divided over his guilt or innocence and the novelty of a black man suing whites in court. That a black man successfully sued the Klan was entirely new, a newspaper at the time opined that the "outcome is regarded as sensational, indicating an entirely new method of dealing with and punishing lawless mobs that have been so numerous in the south."

Leonard Woods was an African-American man who was lynched by a mob in Pound Gap, on the border between Kentucky and Virginia, after they broke him out of jail in Whitesburg, Kentucky, on November 30, 1927. Woods was alleged to have killed the foreman of a mine, Herschel Deaton. A mob of people from Kentucky and Virginia took him from the jail and away from town and hanged him, and riddled his body with shots. The killing, which became widely publicized, was the last in a long line of extrajudicial murders in the area, and, prompted by the activism of Louis Isaac Jaffe and others, resulted in the adoption of strong anti-lynching legislation in Virginia.