Related Research Articles

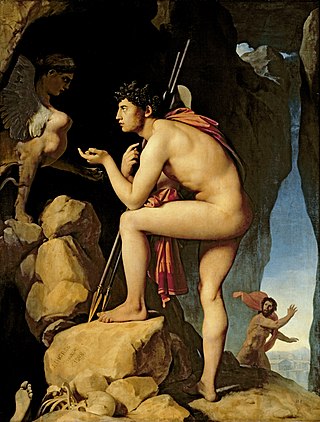

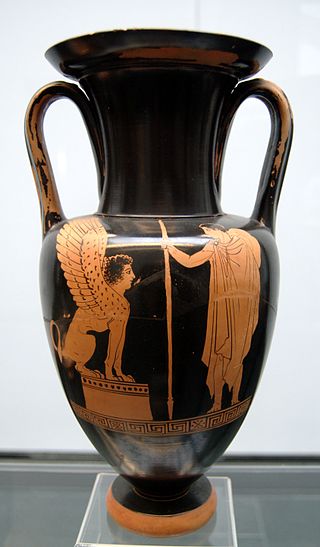

Oedipus was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby bringing disaster to his city and family.

In Greek mythology, Polynices was the son of Oedipus and either Jocasta or Euryganeia and the older brother of Eteocles. When his father, Oedipus, was discovered to have killed his father and married his mother, he was expelled from Thebes, leaving his sons Eteocles and Polynices to rule. Because of a curse put on them by their father Oedipus, the two sons did not share the rule peacefully and died as a result, killing each other in battle for control over Thebes.

Creon, is a figure in Greek mythology best known as the ruler of Thebes in the legend of Oedipus.

In Greek mythology, Tiresias was a blind prophet of Apollo in Thebes, famous for clairvoyance and for being transformed into a woman for seven years. He was the son of the shepherd Everes and the nymph Chariclo. Tiresias participated fully in seven generations in Thebes, beginning as advisor to Cadmus himself.

In Greek mythology, Jocasta, also rendered Iocaste and also known as Epicaste, was a daughter of Menoeceus, a descendant of the Spartoi Echion, and queen consort of Thebes. She was the wife of first Laius, then of their son Oedipus, and both mother and grandmother of Antigone, Eteocles, Polynices and Ismene. She was also sister of Creon and mother-in-law of Haimon.

In Greek mythology, King Laius or Laios of Thebes was a key personage in the Theban founding myth.

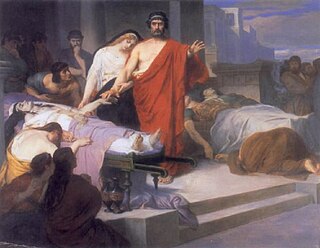

Oedipus Rex, also known by its Greek title, Oedipus Tyrannus, or Oedipus the King, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Greeks, the title was simply Oedipus (Οἰδίπους), as it is referred to by Aristotle in the Poetics. It is thought to have been renamed Oedipus Tyrannus to distinguish it from Oedipus at Colonus, a later play by Sophocles. In antiquity, the term "tyrant" referred to a ruler with no legitimate claim to rule, but it did not necessarily have a negative connotation.

Peripeteia is a reversal of circumstances, or turning point. The term is primarily used with reference to works of literature; its anglicized form is peripety.

The dynastic history of Thebes in Greek mythology is crowded with a bewildering number of kings between the city's new foundation and the Trojan War. This suggests several competing traditions, which mythographers were forced to reconcile.

The Thebaid is a Latin epic poem written by the Roman poet Statius. Published in the early 90s AD, it contains 12 books and recounts the clash of two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, over the throne of the Greek city of Thebes. After Polynices is sent into exile, he forges an alliance of seven Greek princes and embarks on a military campaign against his brother.

Œdipe (Oedipe) is an opera in four acts by the Romanian composer George Enescu, set to a French libretto by Edmond Fleg. It is based on the mythological tale of Oedipus, as told by Sophocles in Oedipus the King.

The Necklace of Harmonia, also called the Necklace of Eriphyle, was a fabled object in Greek mythology that, according to legend, brought great misfortune to all of its wearers or owners, who were primarily queens and princesses of the ill-fated House of Thebes.

Oedipus Rex is a 1967 Italian film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini adapted the screenplay from the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex written by Sophocles in 428 BC. The film was mainly shot in Morocco. It was presented in competition at the 28th Venice International Film Festival. It was Pasolini's first feature-length color film, but followed his use of color in "The Earth Seen from the Moon" episode in the portmanteau film The Witches (1967).

Oedipus is a fabula crepidata of c. 1061 lines of verse that was written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca at some time during the 1st century AD. It is a retelling of the story of Oedipus, which is better known through the play Oedipus Rex by the Athenian playwright, Sophocles. It is written in Latin.

Polybus is a figure in Greek mythology. He was the king of Corinth whose wife was variously referred to as Periboea, Merope or Medusa, daughter of Orsilochus.

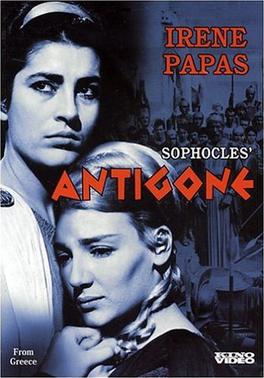

Antigone is a 1961 Greek film adaptation of the Ancient Greek tragedy Antigone by Sophocles. It stars Irene Papas in the title role and was directed by Yorgos Javellas.

Oedipus rex is an opera-oratorio by Igor Stravinsky, scored for orchestra, speaker, soloists, and male chorus. The libretto, based on Sophocles's tragedy, was written by Jean Cocteau in French and then translated by Abbé Jean Daniélou into Latin; the narration, however, is performed in the language of the audience.

Oedipus is a play by the 5th-century BCE Athenian dramatist Euripides. The play is now lost except for some fragments. What survives of the play covers similar ground as Sophocles' acclaimed Oedipus Rex, but scholars and historians have found there are significant differences. In Oedipus Rex, the title character blinds himself upon learning his true parentage, accidentally killing his father and marrying his mother Jocasta. In Euripides' play, however, it appears Oedipus is blinded by a servant of his father Laius, Oedipus' predecessor as king of Thebes. Furthermore, Euripides' play implies Oedipus was blinded before it was known that Laius was his father. Also, while in Sophocles' play Jocasta kills herself, remaining fragments of Euripides' play depict Jocasta as having survived and accompanied Oedipus into exile.

In Greek mythology, Merope was a Queen of Corinth, and wife of King Polybus. In some accounts, she was called Periboea.

References

- ↑ David Bradby. "Cocteau, Jean" in The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, ed. Martin Banham, 1988. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 225 pp. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- ↑ Jean Cocteau, The Infernal Machine & Other Plays, New Directions, 1964. ISBN 978-0811221634.

- ↑ Stephen Holden, "Review: Cocteau's Humanized Oedipus", The New York Times, 2 Dec. 1990. Accessed 1 July 2015.

- 1 2 Feynman, Alberta (May 1963). "The Infernal Machine, Hamlet, and Ernest Jones". Modern Drama. Univ. of Toronto Press. 6 (1): 72–83. doi:10.3138/md.6.1.72. S2CID 194080631.