Related Research Articles

Sequence stratigraphy is a branch of geology, specifically a branch of stratigraphy, that attempts to discern and understand historic geology through time by subdividing and linking sedimentary deposits into unconformity bounded units on a variety of scales. The essence of the method is mapping of strata based on identification of surfaces which are assumed to represent time lines, thereby placing stratigraphy in chronostratigraphic framework allowing understanding of the evolution of the earth's surface in a particular region through time. Sequence stratigraphy is a useful alternative to a purely lithostratigraphic approach, which emphasizes solely based on the compositional similarity of the lithology of rock units rather than time significance. Unconformities are particularly important in understanding geologic history because they represent erosional surfaces where there is a clear gap in the record. Conversely within a sequence the geologic record should be relatively continuous and complete record that is genetically related.

The Acadian orogeny is a long-lasting mountain building event which began in the Middle Devonian, reaching a climax in the early Late Devonian. It was active for approximately 50 million years, beginning roughly around 375 million years ago, with deformational, plutonic, and metamorphic events extending into the Early Mississippian. The Acadian orogeny is the third of the four orogenies that formed the Appalachian orogen and subsequent basin. The preceding orogenies consisted of the Potomac and Taconic orogeny, which followed a rift/drift stage in the Late Neoproterozoic. The Acadian orogeny involved the collision of a series of Avalonian continental fragments with the Laurasian continent. Geographically, the Acadian orogeny extended from the Canadian Maritime provinces migrating in a southwesterly direction toward Alabama. However, the Northern Appalachian region, from New England northeastward into Gaspé region of Canada, was the most greatly affected region by the collision.

The Taconic orogeny was a mountain building period that ended 440 million years ago and affected most of modern-day New England. A great mountain chain formed from eastern Canada down through what is now the Piedmont of the East coast of the United States. As the mountain chain eroded in the Silurian and Devonian periods, sediments from the mountain chain spread throughout the present-day Appalachians and midcontinental North America.

A marine transgression is a geologic event during which sea level rises relative to the land and the shoreline moves toward higher ground, which results in flooding. Transgressions can be caused by the land sinking or by the ocean basins filling with water or decreasing in capacity. Transgressions and regressions may be caused by tectonic events such as orogenies, severe climate change such as ice ages or isostatic adjustments following removal of ice or sediment load.

A cratonic sequence in geology is a very large-scale lithostratigraphic sequence in the rock record that represents a complete cycle of marine transgression and regression on a craton over geologic time. They are geologic evidence of relative sea level rising and then falling, thereby depositing varying layers of sediment onto the craton, now expressed as sedimentary rock. Places such as the Grand Canyon are a good visual example of this process, demonstrating the changes between layers deposited over time as the ancient environment changed.

The Sauk sequence was the earliest of the six cratonic sequences that have occurred during the Phanerozoic in North America. It was followed by the Tippecanoe, Kaskaskia, Absaroka, Zuñi, and Tejas sequences.

The Kaskaskia sequence was a cratonic sequence that began in the mid-Devonian, peaked early in the Mississippian, and ended by mid-Mississippian time. A major unconformity separates it from the lower Tippecanoe sequence, called the "Wallbridge Unconformity".

West Virginia's geologic history stretches back into the Precambrian, and includes several periods of mountain building and erosion. At times, much of what is now West Virginia was covered by swamps, marshlands, and shallow seas, accounting for the wide variety of sedimentary rocks found in the state, as well as its wealth of coal and natural gas deposits. West Virginia has had no active volcanism for hundreds of millions of years, and does not experience large earthquakes, although smaller tremors are associated with the Rome Trough, which passes through the western part of the state.

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, although originally it also included the cratonic areas of Greenland and also the northwestern part of Scotland, known as the Hebridean Terrane. During other times in its past, Laurentia has been part of larger continents and supercontinents and itself consists of many smaller terranes assembled on a network of Early Proterozoic orogenic belts. Small microcontinents and oceanic islands collided with and sutured onto the ever-growing Laurentia, and together formed the stable Precambrian craton seen today.

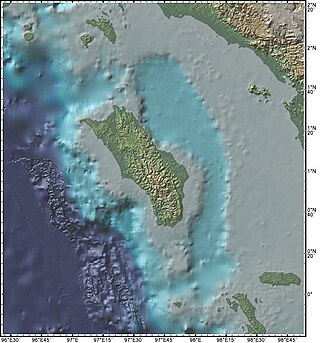

The Nias Basin is a forearc basin located off the western coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, in the Indian Ocean. The name is derived from the island that bounds its western edge, the island of Nias. The Nias Basin, the island of Nias, and the offshore, submarine accretionary complex, together form a Forearc region on the Sunda Plate/Indo-Australian Plate collisional/subduction boundary. The Forearc region is the area between an oceanic trench and its associated volcanic arc. The oceanic trench associated with the Nias Basin is the Sunda Trench, and the associated volcanic arc is the Sunda Arc.

The Precordillera terrane of western Argentina is a large mountain range located southeast of the main Andes mountain range. The evolution of the Precordillera is noted for its unique formation history compared to the region nearby. The Cambrian-Ordovian sedimentology in the Precordillera terrane has its source neither from old Andes nor nearby country rock, but shares similar characteristics with the Grenville orogeny of eastern North America. This indicates a rift-drift history of the Precordillera in the early Paleozoic. The Precordillera is a moving micro-continent which started from the southeast part of the ancient continent Laurentia. The separation of the Precordillera started around the early Cambrian. The mass collided with Gondwana around Late Ordovician period. Different models and thinking of rift-drift process and the time of occurrence have been proposed. This page focuses on the evidence of drifting found in the stratigraphical record of the Precordillera, as well as exhibiting models of how the Precordillera drifted to Gondwana.

The geology of Western Sahara includes rock units dating back to the Archean more than two billion years old, although deposits of phosphorus formed in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic have helped to prompt the current Moroccan occupation of most of the country.

The geology of Ohio formed beginning more than one billion years ago in the Proterozoic eon of the Precambrian. The igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rock is poorly understood except through deep boreholes and does not outcrop at the surface. The basement rock is divided between the Grenville Province and Superior Province. When the Grenville Province crust collided with Proto-North America, it launched the Grenville orogeny, a major mountain building event. The Grenville mountains eroded, filling in rift basins and Ohio was flooded and periodically exposed as dry land throughout the Paleozoic. In addition to marine carbonates such as limestone and dolomite, large deposits of shale and sandstone formed as subsequent mountain building events such as the Taconic orogeny and Acadian orogeny led to additional sediment deposition. Ohio transitioned to dryland conditions in the Pennsylvanian, forming large coal swamps and the region has been dryland ever since. Until the Pleistocene glaciations erased these features, the landscape was cut with deep stream valleys, which scoured away hundreds of meters of rock leaving little trace of geologic history in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic.

The geology of Missouri includes deep Precambrian basement rocks formed within the last two billion years and overlain by thick sequences of marine sedimentary rocks, interspersed with igneous rocks by periods of volcanic activity. Missouri is a leading producer of lead from minerals formed in Paleozoic dolomite.

The geology of Utah, in the western United States, includes rocks formed at the edge of the proto-North American continent during the Precambrian. A shallow marine sedimentary environment covered the region for much of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, followed by dryland conditions, volcanism, and the formation of the basin and range terrain in the Cenozoic.

The geology of the State of New York is made up of ancient Precambrian crystalline basement rock, forming the Adirondack Mountains and the bedrock of much of the state. These rocks experienced numerous deformations during mountain building events and much of the region was flooded by shallow seas depositing thick sequences of sedimentary rock during the Paleozoic. Fewer rocks have deposited since the Mesozoic as several kilometers of rock have eroded into the continental shelf and Atlantic coastal plain, although volcanic and sedimentary rocks in the Newark Basin are a prominent fossil-bearing feature near New York City from the Mesozoic rifting of the supercontinent Pangea.

The geology of North Dakota includes thick sequences oil and coal bearing sedimentary rocks formed in shallow seas in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, as well as terrestrial deposits from the Cenozoic on top of ancient Precambrian crystalline basement rocks. The state has extensive oil and gas, sand and gravel, coal, groundwater and other natural resources.

The geology of Denmark includes 12 kilometers of unmetamorphosed sediments lying atop the Precambrian Fennoscandian Shield, the Norwegian-Scottish Caledonides and buried North German-Polish Caledonides. The stable Fennoscandian Shield formed from 1.45 billion years ago to 850 million years ago in the Proterozoic. The Fennoscandian Border Zone is a large fault, bounding the deep basement rock of the Danish Basin—a trough between the Border Zone and the Ringkobing-Fyn High. The Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone is a fault-bounded area displaying Cretaceous-Cenozoic inversion.

The geology of Yukon includes sections of ancient Precambrian Proterozoic rock from the western edge of the proto-North American continent Laurentia, with several different island arc terranes added through the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, driving volcanism, pluton formation and sedimentation.

The Parnaíba Basin is a large cratonic sedimentary basin located in the North and Northeast portion of Brazil. About 50% of its areal distribution occurs in the state of Maranhão, and the other 50% occurring in the state of Pará, Piauí, Tocantins, and Ceará. It is one of the largest Paleozoic basins in the South American Platform. The basin has a roughly ellipsoidal shape, occupies over 600,000 km2, and is composed of ~3.4 km of mainly Paleozoic sedimentary rock that overlies localized rifts.